Whats for dinner? Bread? Sex? Betrayel?

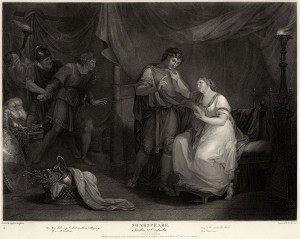

In “Troilus and Cressida,” Shakespeare uses food imagery everywhere as a thinly veiled euphemism for sexual and carnal desire. Appealing to the crowd, Shakespeare knows that he’s among commoners who spend time drinking at taverns, wasting money away on whoring and gambling. Some of the male characters’ “hungry desires” for women probably reflect the viewers’ cravings for members of the female population. This male-female dynamic is especially inherent in the supposed “romance” between Troilus and Cressida.

Describing Troilus’ interest in his daughter, Pandarus likens the prince’s hunger to baking and eating a cake. Reminding Troilus that he must “tarry” the “grinding, “bolting,” “leavening,” and “kneading” of the cake, Pandarus gladly offers his Cressida as a baked dessert to this greedy hero.The multitude innuendos in Pandarus’ dialogue suggest that Cressida is no more than a tasty object of sexual consummation for Troilus. While Cressida doesn’t have the same gorgeous characteristics as Helen, the other major female character in the play, Troilus finds the young woman irresistible. In another part of the play, Troilus eagerly waits to “taste… [Cressida’s] thrice-repured nectar” (III.2.19-20). Whether he truly loves Cressida in the romantic sense, or if he sees the girl as a delectable treat that can gratify his carnal and “hungry needs” remains a question.

Things turn sour, however, when Cressida betrays Troilus by promising her love to Diomedes, a Greek soldier. Casting her out of his life, Troilus states:

“The fractions of her faith, the orts of her love,/ The fragments, scraps, the bits, and the greasy relics/ Of her o’reaten faith, are bound to Diomed” (V.2.161-163)

Troilus believes the “orts” (read as leftovers) of Cressida’s love to be greasy pieces of fat and scraps, deserving of only the lowliest of creatures. In a way, Troilus suggests that Cressida’s new lover will never have the same prime “meat” that he once enjoyed by consummating his love with his backstabbing lover. Cressida was a sexual delicacy when she made love to Troilus, but now that she has moved on, she has lost her “delicious” quality that Troilus initially saw in her.

In “The Gastric Epic: Troilus and Cressida,” David Hillman examines the “misanthropic cannibalism of satire” in the play, relating the concept to the constant use of food and eating done by characters like Troilus (Hillman 303). To Hillman, the “projective mechanism of satire… makes it both embody and thematize a cannibalistic urge” in literature (Hillman 303). He states that a distinct pattern emerges when looking at the “figurative trajectory” of food as the play moves on. Like the description of food mentioned above, the play transitions from delicious descriptions of oven cooked treats to disgusting, reused pieces of offal, fit for nothing more than swine.

What I find thought-provoking in Hillman’s essay is his belief that satirical cannibalism exists in T & C. He argues that the “entire project, comprising Shakespeare’s relation to his sources, the audience’s relation to the play, and the characters’ relation to each other- is implicitly cannibalistic” (Hillman 305). Troilus’s relationship with Cressida satirizes the idea of a man naively viewing a woman as the epitome of perfection. In an almost nauseating way, Troilus lowers the passion he has for Cressida to one would have for food. By relating their sexual consummation to food, Troilus also symbolically cannibalizes on Cressida’s “delicious” qualities to maintain his illusion of female beauty. Once his source of ladylike beauty has been tainted, literally by the love of another man, Troilus scrambles to maintain his fantasy by quickly discarding Cressida. Troilus metaphorically regurgitates Cressida, leaving her as disgusting refuse to consumed up by bottom feeders like Diomedes.

Sources:

1. Hillman, David. ‘The Gastric Epic: Troilus And Cressida’. Shakespeare Quarterly 48.3 (1997): 295. Web.