Re-imagining Shakespeare is not a new concept. Just recently, the Dartmouth College Department of Theater reimagined Romeo and Juliet as a more experimental production, setting it in a rehearsal studio and using video cameras to record the action, so that the audience watches the actors both on stage and on monitors and a large video screen. Peter Hackett, the director of the winter main stage, wanted to highlight the less-obvious more salient aspects that are not as often explored in a traditional Shakespearean manner. Challenging the conventional view, Hackett wanted the audience to ponder and be critical of what was being presented to them on stage. “It forces you as an audience not to sit back and have your expectations met. … I hope the effect is that it makes you listen to what is being said,” Hackett said.

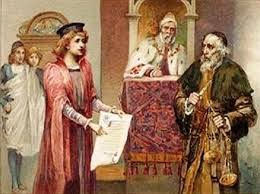

In Mobile Carnival Theatre Company’s reimagining of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, director Brent Murrill, like Dartmouth theater director Peter Hackett, reimagined Shakespeare’s traditional setting in a more contemporary fixture.