Re-imagining Shakespeare is not a new concept. Just recently, the Dartmouth College Department of Theater reimagined Romeo and Juliet as a more experimental production, setting it in a rehearsal studio and using video cameras to record the action, so that the audience watches the actors both on stage and on monitors and a large video screen. Peter Hackett, the director of the winter main stage, wanted to highlight the less-obvious more salient aspects that are not as often explored in a traditional Shakespearean manner. Challenging the conventional view, Hackett wanted the audience to ponder and be critical of what was being presented to them on stage. “It forces you as an audience not to sit back and have your expectations met. … I hope the effect is that it makes you listen to what is being said,” Hackett said.

In Mobile Carnival Theatre Company’s reimagining of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, director Brent Murrill, like Dartmouth theater director Peter Hackett, reimagined Shakespeare’s traditional setting in a more contemporary fixture.

Set during WWII inside the Theresienstadt (Terezin) concentration camp in what is now the Czech Republic, the play presents the actors as prisoners, mostly Jews, along with gypsies, homosexuals and other “undesirables,” who stage the production at the behest of the Schutzstaffel camp commandant.

The challenge for Murrill and his dramaturg Moira Amado-McGittigan was to straddle the two worlds at hand: the safety of a Shakespearean play and its potentiality of polarization among the audience.

“The question was how to produce ‘Merchant’ without playing into the repulsive nature (of the character). Is there a possibility of making it ironic when there’s nothing in the text that makes it ironic?” (Source)

Shakespeare, in the simplest sense of the word, implies the catholic (little c) universality of his plays as the accepted catalogue of plays to produce time and time again. Tragedy to comedy, Romeo and Juliet to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Shakespeare’s plays attract audience members regardless of their romanticized issues or stereotyped caricatures. Fully aware of the Bard’s popularity, this allowed for Murrill and Amado-McGittigan to challenge the traditional framework of the play and offer their own vision and commentary on anti-Semitism and the Shoah.

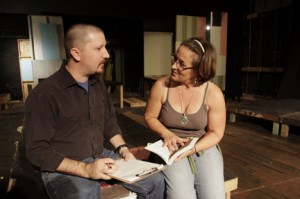

Director Brent Murrill and dramaturg Moria Amado-McGittigan discuss Mobile Carnival Theatre Company’s production of “The Merchant of Venice.”

The potentiality of polarization of their reimagining of The Merchant of Venice lies in the director’s ability to offer a poignant presentation of their vision while abiding by the motivations and text of the original work. Audiences will not readily flock to a totally experimental adaptation of a Shakespearean classic unless the new play builds upon or offers a new medium in which to explore the original context, such as placing sixteenth century Venice in Holocaust Czechoslovakia.

The Mobile Carnival Theater Company portrays Shylock and the rest of the cast as Jewish concentration camp victims in Theresienstadt staging a play for their Nazi leaders and fellow Jewish victims. As Jewish people portraying virulent anti-Semitic Venetians and stereotyped caricatures of themselves, the actors are playing dual roles. Forced to play these roles by their Nazi commandants, these actors find through the work of the play that The Merchant of Venice is much more than an anti-Semitic reading of Venice. It is the telling of the story of being human beings during the time of the Holocaust and how as Jews, these men and women were looked down on and viewed as subhuman by the Nazi regime.

Most telling of this fact is contained in Shylock’s classic monologue:

Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions; fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, heal’d by the same means, warm’d and cool’d by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? (Act III, Scene I, lines 58-67)

Shylock, as portrayed by a Jew, in a play staged by the Nazis to uphold the anti-Semitism on Jews at the time in the German state, is a reflection of all the actors on the stage. The setting of the concentration camp theater space, where in fact there were on-site theaters dedicated to providing prisoners with entertainment and a forum for arts and cabaret, adds layers of meaning to every piece of dialogue spoken and reacted on by the characters in the scenes.

At the conclusion of his reimagining, Murrill provides an alternative and thought-provoking ending that leaves the audience with a sense of gripping reality and finality that Shakespeare’s original play fails to do. Throughout the production of the paly within the play, the Jewish concentration camp victims grow into their roles and become more active in the dialogue surrounding anti-Semitism in the Nazi regime. At the end of the play, Murrill tweaked the ending by having the Schutzstaffel guard interrupt the play and order the prisoners to clean up. Members of the company begin to put things back into place, shed costume pieces and return to the bleak world of Terezin.

By ending so suddenly, the trauma of the situation sets in. These actors are still Jewish concentration camp victims. They are still in Nazi controlled Czechoslovakia and still at any moment victim to the gas chambers. But, the actors appear less sullen, more hopeful of change to come in the future. Through the play, the actors have embraced one another and found hope. They are hopeful that their situation is not a permanent situation. There is the hope that the anti-Semitism faced by the Jews is an absolute moral wronging and that there is a chance for growth and community to develop.

Cast members of the Mobile Carnival Theatre Company rehearse the closing scene in “The Merchant of Venice,” set in a World War II prison camp. From left: Mike Green, Kristen Lazarchek, Andrew Weber and Erika Hakmiller.

Through their reimagining of a Shakespeare classic, the MCTC offers a refreshing and poignant take upon the realities faced by Jews during the Shoah and the petulant anti-Semitism that was in place at the time of Shakespeare’s Venice. Through the helpful work that Jewish scholars such as Elie Wiesel and Primo Levi have put out about the realities of the Shoah and Nazi revisionism, retellings of productions such as this Merchant of Venice continue to provoke discussion and dialogue on the not-so-far-removed past.

Sources:

http://www.vnews.com/lifetimes/15724202-95/dartmouth-production-reframes-romeo-and-juliet-around-issues

http://blog.al.com/entertainment-press-register/2010/07/mctcs_merchant_of_venice_takes_shake.html

http://www.canadianshakespeares.ca/a_auschwitz.cfm