Chris: Do they know… Do they know I’m black?

Rose: No.

Chris: Should they? It seems like… something you might want to know… mention.

Rose: Mom and Dad, my uh, my black boyfriend will be coming up this weekend… and I just don’t want you to be shocked because he’s a black man.

Chris: You said I was the first black guy you ever dated?

Rose: Yeah, so what?

Chris: Yeah, so this is uncharted territory for them. You know I don’t want to be chased off the lawn with a shotgun.

Rose: You’re not going to. First of all, my dad would have voted for Obama a third time if he could have. Like, the love is so real… They are not racist. I would have told you. I wouldn’t be bringing you home to them.

Rose is innocent. No matter what. Or, at least, that’s how she sees it. Again and again, in every scene she is in, Rose casts herself in the light of the innocent, good, pure-hearted white woman. She is the white woman who is progressive, because she is dating her first-ever (!) black man, she is the white woman who is brave, because she stands up for him in front of a cop, and she is the white woman who is good and pure because she is white and female, even when she finally unmasks herself with “You know I can’t give you those keys, right, babe?”

Rose’s conversations with her boyfriend-slash-victim Chris are carefully chosen words that show how innocent a person Rose sees herself as. Her actions do not speak louder than her words because her actions are almost entirely passive. In every case, Rose does not really act aggressively, but it is that absence of thought that show the white woman privilege Rose capitalizes on. We can see this through analyzing several of her conversations with Chris.

In the introductory scene above, Rose casts herself as the woman who comes from a progressive background, who loves her black boyfriend, and who has not fallen prey to the beauty standards of white-driven media, because she has a black boyfriend. In mocking Chris’s concerns over her white family’s racism, Rose plays the aware girlfriend who understands race relations that she is not on the receiving end of. As a white woman, she is not threatened by racism, and as a white woman, she cannot see how she—innocent and nonthreatening—can be a member of a community who would oppress people of color. “They are not racist. I would have told you. I wouldn’t be bringing you home to them.” Rose believes she understands the black experience, and she casts herself in the dominant role in the relationship as the protector of the black man.

Police: Sir, can I see your license, please?

Rose: Wait, why?

Chris: Yeah, I have a state ID.

Rose: No, no, no. He wasn’t driving.

Police: I didn’t ask who was driving. I asked to see his ID.

Rose: Yeah, why? That doesn’t make any sense.

Chris: Here.

Rose: No, no, no. Fuck that. You don’t have to give him your ID because you haven’t done anything wrong.

Chris: Baby, baby, it’s okay. Come on.

Police: Anytime there is an incident we have every right to ask…

Rose: That’s bullshit.

Rose’s role as the innocent, progressive protector of the black man continues in the above dialogue. After Rose hits a deer in her car, a policeman comes and Rose finds an opportunity to push forward her innocent yet aware warrior agenda. She appears to stand up for Chris, using her awareness of her white privilege—and her awareness of her automatically innocent status as a white woman—to protect Chris from the policeman. However, by inserting herself into the situation, she could have escalated it. Her role is not to protect him, it is to progress the image she has of herself. If she can convince herself she understands the relationship between Chris and the white policeman, she can absolve herself of racism, which is what she is most terrified of. Her second agenda in not allowing the police officer to see Chris’s ID is not immediately apparent. If the officer sees his ID, he will have a paper trail of proof that Rose and Chris were together immediately before Chris goes missing, which undermines her alternative agenda.

Chris: I mean, how are they different from that cop?

…

Rose: I don’t like being wrong.

Chris: I’ve noticed that.

Rose: I am sorry.

Chris: No, no, no. Wait, come here.

Rose: Sorry. This sucks.

Chris: What? Why do you say you’re sorry?

Rose: Because I brought you here and I’m related to all of them.

Blaming yourself is a classic, well-known, and generally considered rather irritating and insincere way of absolving yourself of the blame. Rose realizes that her family is not as “not racist” as she would like to think they are—and by extension, herself. By blaming herself, Rose is forcing Chris to say that she is not guilty, that she is different, that she is the young, attractive, desirable white woman who does not hold the blame for racism because she, too, is a victim of the patriarchy. Rose is desperate in this scene to be absolved of any guilt, and in doing so, she again forces Chris to cast her as the progressive, innocent white woman.

Chris: Rose, give me those keys. Give me those keys! Rose, now, now! The keys!

Jeremy: Whoa, be careful, bro.

Chris: Where are those keys, Rose?

Rose: You know I can’t give you the keys, right, babe?

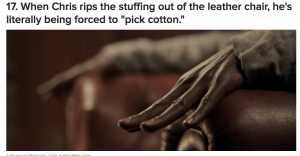

As Chris is desperately trying to get out of the Armitage’s house with the family blocking him and supposedly with only Rose on his side, Rose suddenly turns on him. The way she does it, however, is so unlike everybody else. Missy’s hypnotism is innately sinister and terrifyingly controlling. She is the slave driver—literally—who controls her slaves through the essence of elitism and colonialism: a china tea cup. Dean’s re-enactment of a slave auction while his daughter and Chris take a walk in the woods has long since betrayed his own blatantly racist motives. Jeremy’s brandishing of the lacrosse stick (a game often associated with upper-class white privilege, particularly on the East Coast) casts him as the violent racist. And while Chris gets more and more agitated and starts getting angry with Rose because of his frustration and fear, Rose begins to act pitiful. She is not the warrior protectress, but the innocent white woman being yelled at by her black boyfriend who cannot possibly be on the bad side. And it is in this mix of the Armitage’s violence against Chris and Chris’s anger and frustration that Rose simultaneously blames Chris for her “switch” and excuses herself from it. Her statement is incredibly patronizing, emphasizing the white privilege that she pretends to not want. It is the same sentence that might be said to a drunk boyfriend who promises that he can drive home; it is the sentence that says “I know what is best for you,” and laughs at the drunk boyfriend for thinking he has any say in the matter. She calls him “babe” to recall her relationship to him and to emphasize her power over him and manipulation of him. While everybody else is brandishing a lacrosse stick or a cup of tea and running around, Rose’s calm presence stands out as the most dangerous of all.

In a scene with no dialogue, Rose sips on a white cup of milk while eating a separate cup of colored cereal. The symbolism here is obvious, but what is equally as jarring is the transition from the previous scene to now. In the previous scene, Chris fights Missy off brutally. He has the obvious physical advantage but with her teacup, he has no chance against her. Yet, he wins, and he is panting, dark, and sweating after his violent fight. Contrast that with the slicked-back, white-clothed Rose, calmly sitting in her childhood bedroom. While he is fighting for his life, she has already forgotten about him as she sits searching for her next boyfriend. While their relationship is tightly woven for him, with her effects long-lasting and devastating to him, she is calm and problem-free. She has cut her ties, but he is unable to cut his. By removing herself from the situation and through using her earbuds, Rose retains her innocence of the terrible acts and desperate fight going on downstairs. She is the blissfully innocent white woman, even when proven guilty. Additionally, as she searches for potential boyfriends, she sits confidently in her knowledge that as the white woman, she is attractive. She is the white female lure that black men cannot resist, and who will be able to snatch them from their lives, families, and friends with little difficulty, because she is beautiful, innocent, and most importantly: white.

In the final scene, as the police car rolls up, Rose gleefully takes advantage of her white womanhood to place herself as the innocent victim of the whole scene. With the police lights flashing, Rose knows that the police have seen Chris kneeling over her, threatening her with apparently no violence on her part, and she reaches out to them: “Help…” Chris knows that she has won, too. He stands up, he puts his hands up, and he is desperately resigned to his unfair, racialized and gendered fate at the hands of the beautifully innocent white woman. Although in the end, Chris is rescued by his best friend, this moment could have so easily remained the well-known trope of the innocent white woman brutalized by the wild black man, successfully cast, directed, and acted by Rose’s white womanhood.

Connection to Readings

“We must face the dominant US ideology: that our culture represents the epitome of women’s liberation. Gendered oppression is largely considered irrelevant to women in the USA — a blight instead reserved for people in other countries.” – Huibin Chew, Feminism and War: Confronting US Imperialism

Rose is constantly insinuating that she represents the epitome of a not-racist woman. She believes that she always has the better understanding of interracial relationships than Chris does and that she is able to make the better choices for him because she lives in what she believes to be a post-racial society. Additionally, although she is masterfully using the image of the innocent white woman, Rose seems unaware that her self-representation is a reflection of the patriarchy’s view of white women as a group of lesser people that must be protected, particularly from black men.