Native Americans were originally only included in the census if they lived under US jurisdiction. Because Native Americans were largely considered independent, they were excluded from the census and were not apportioned Congressional representatives. “Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed” (Article 1, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution).

The 1850 census is the first census that allows us to look at individual Native Americans and how they were counted in the census. With Native American census data and enumerator instructions, we can better understand how the federal government understood Native Americans as a race and the relationship between the federal government and Native Americans.

Data & Method:

I collected census data from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series- United States of American (IPUMS-USA). My census data includes 1% samples from 1850 to 1950.

I exclude Hawaii and Alaska from my analyses, as they were not US territories until 1898 and 1912. Additionally, the 1940 and 1950 censuses do not include Alaska or Hawaii. I also exclude any other US territories and overseas military bases. Hawaii, Alaska and other territories would skew my data and offer little value to my analyses.

Unfortunately, the destruction of the 1890 census prevents us from fully analyzing the affect government policies had on the enumeration of Native Americans between 1881 and 1900. The 1900 census was the first census all Native Americans were enumerated, regardless of tribal affiliations or where they lived.

I first assigned each RACED category a label for the correct race. I weighted each individual’s weight with IPUMS PERWT variable and then summed each racial category by year with the PERWT variable. Next I split the racial categories into “Native American” and “Rest of Population (Not Native).” I then plotted the Native American population. Finally, I used Microsoft Excel to tidy up and display my table.

Results:

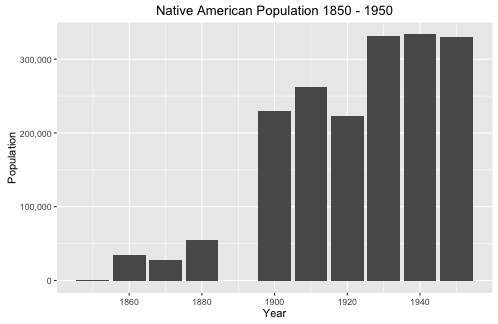

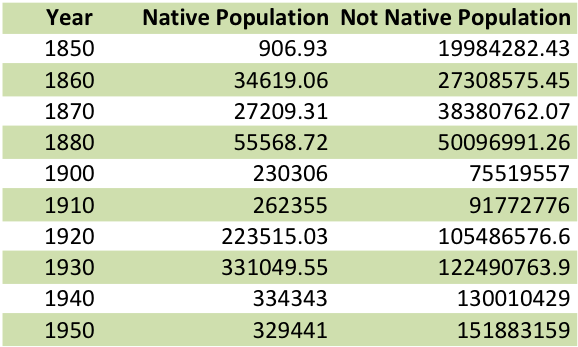

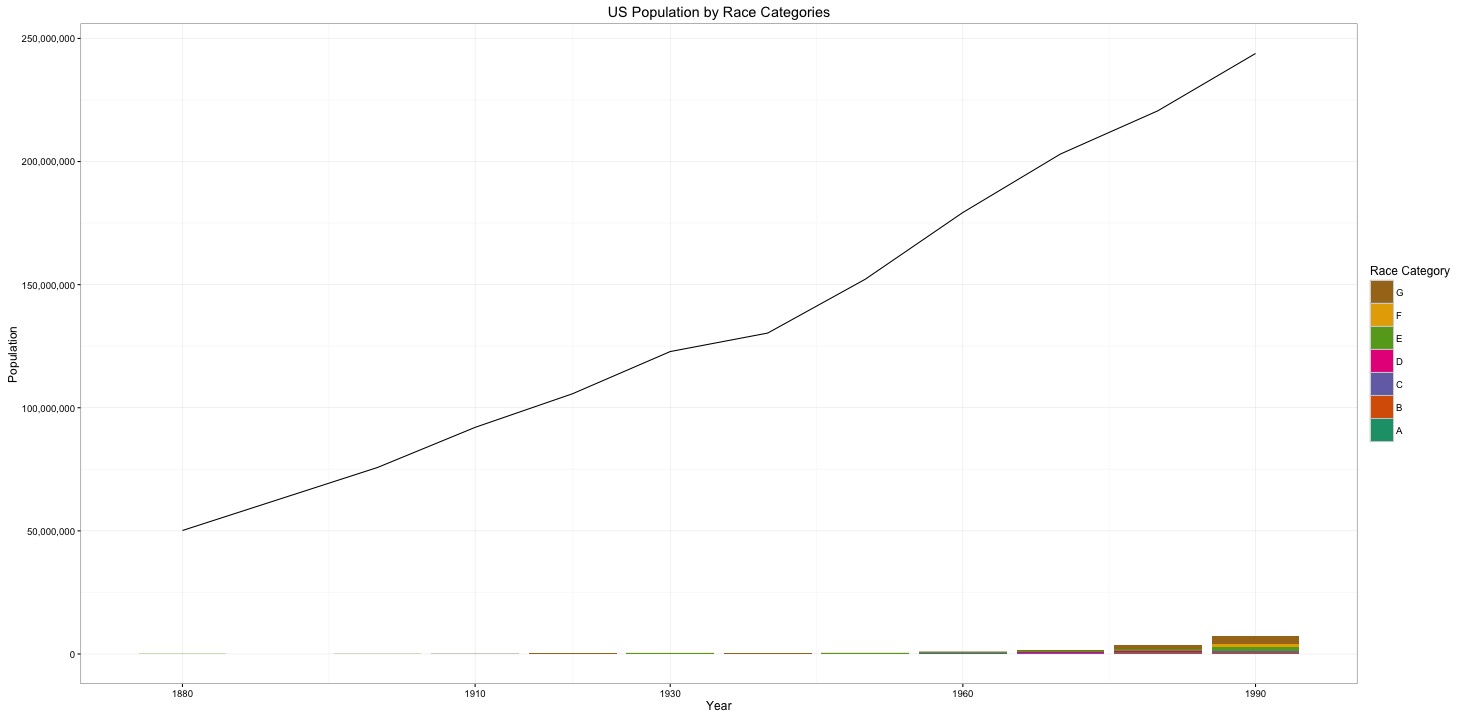

Figure 1 depicts the population of Native Americans from 1850 to 1950. During this time, Native American counted in the census increased from 907 to 329,441, an amazing 36,222% increase. Meanwhile, the overall American population only increased 660%. Figure 2 displays the exact population numbers for each year and compares Native Americans to non-Native Americans. Figure 2 proves that the Native American population boom can only be explained by changes in how Native Americans were enumerated in the census.

Figure 2 displays the exact population numbers for each year and compares Native Americans to non-Native Americans. Figure 2 proves that the Native American population boom can only be explained by changes in how Native Americans were enumerated in the census.

The 1850 Census Enumerator Instructions maintain the same instructions used since the 1790 Census, “Indians not taxed are not to be enumerated in this or any other schedule,” however, in 1860, the instructions for Native Americans start to become more complex. Now, “Indians who have renounced tribal rule, and who under State or Territorial laws exercise the rights of citizens, are to be enumerated,” and were assigned a distinct racial category of “Ind.” Native Americans’ race was determined by their lack of tribal affiliation and U.S. citizenship. Now that Native Americans had been assigned a distinct racial category, their census numbers increase by 3,817%.

In 1870 enumeration instructions again changed for Native Americans. The census found it “highly desirable, for statistical purposes” to count Native Americans, not taxed, living on reservations. However, the 1880 census gave less instructions on how to count Native Americans. Native Americans not taxed were now defined to be those “living on reservations under the care of Government agents” ( Enumerators were also instructed to count Native Americans as “ordinary” (or white) if they lived in society. This new definition and categorization may be because of the Indian Appropriation Act of 1871 which declared, “No Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation” and created reservations (25 USC 71, 1871).

By 1890 and 1900, enumerator instructions no longer included any mention of “Indians not-taxed” or instructions on how to classify Native Americans. Enumerators were instructed to write “Ind.” for Native Americans. As Prewitt noted, the Indian Wars ended by 1886 and “the red race [was] assimilated” (Prewitt 2013, 36). By 1900, all Native Americans were counted in the census. The Indian question was solved by 1900 (Prewitt 2013, 36). However, if the Indian question was truly solved then there would be no reason to categorize and assimilate Native Americans as white after 1900.

The loss of the 1890 census data makes it difficult to analyze the affect the Dawes Act had on the counting of Native Americans in the census. The Dawes Act of 1887 allowed the president to forcibly assimilate Native Americans by terminating their reservation, granting those Native Americans citizenship and individual land parcels to live and farm on.

In 1930, Native Americans were classified as Indian according to blood quanta. However, a Native American was capable of being classified as white if “he is regarded as a white person by those in the community where he lives.” The census enumerator instructions supports Prewitt’s claim that Native Americans are able to assimilate and become white. Native Americans classified as white are difficult to find in the census as they are no longer classified as “Ind.” in the census. Other variables such as MBPL and FBPL may help us identify Native Americans reclassified as white. The 1940 and 1950 census enumerator instructions continue to use blood quanta and acceptance in the community to determine if someone is racially Native American.

Conclusion

Native Americans were considered to be an assimilable race by the U.S. government in order to force Native Americans onto reservations and strip them of their sovereign nation rights and treaties. Census enumerator instructions show how over the decades, Native Americans were counted for non-taxable purposes, and then increasingly counted and counted as whites. Native Americans’ racial status changed as the federal government’s desire for Native American land changed. Once the Native Americans had been stripped of their land, they were classified according to conventional blood quanta measurements and community acceptance criteria which allowed them to be categorized as white.

Works Cited

Article 1, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution. http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=9&page=transcript

“Dawes Act.” Dawes Severalty Act Of 1887 (2009): 1. Our Documents. Web. 25 Jan. 2016. http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=50&page=transcript

“Indian Apportionment Act of 1871,” 25 US Code 71, 1871. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/25/71

IPUMS and IPUMS Census Enumerator Instructions (https://usa.ipums.org/usa/voliii/tEnumInstr.shtml)

Prewitt, Kenneth. “The Compromise that Made the Republic and the Nation’s First Statistical Race.” What Is Your Race?: The Census and Our Flawed Efforts to Classify Americans. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 2013. N. pag. Print.