Troilus and Cressida has been read as a tragedy, a history, and a black comedy. It has a dual plot line featuring a tragic love story and a political war drama. But what you won’t find in the Sparknotes summary of Troilus and Cressida is that it’s really a story that’s part mystery, part cautionary tale about Pandarus’s syphilis.

The play both opens and closes with references to venereal disease. During the first scene, Troilus laments to Pandarus about his desire for Cressida. He describes his impatience to be with her through a series of metaphors about bread-making. Almost all of these metaphors, including his desire for “grinding” and “bolting” can be interpreted as sexual innuendos. “Bolting” was actually a particularly crude sexual innuendo at the time of writing. However, Pandarus encourages Troilus to be patient and warns him to be careful, else he “may chance burn [his] lips” (I.1.26). This warning could be a veiled reference to venereal disease (because it burns…sorry for that). This possibility becomes even more likely when the reader discovers later in the play that Pandarus himself has syphilis! In fact, the entire final speech of the play is a lament, by Pandarus, about his poor health. He describes a horrible aching in his bones, a common symptom of syphilis. He also says that he plans to ease his ailments by sweating, or taking steam baths, which was a commonly used remedy for syphilis during the 17th century (Pelican). And if all those hints weren’t clear enough, he makes his condition quite clear when he promises to pass on his “diseases” (V.10.55) to the prostitutes of his favorite brothels until the rest of his days. Nice.

It makes sense that the French disease would feature prominently in Shakespeare’s work. Although syphilis did not take root in Europe until the late 15th century, making it historically unlikely that the Greeks and Trojans would have encountered it, it was a big problem during Shakespeare’s time. The strain of syphilis in pre-penicillin times was considerably more severe than the syphilis we know today. It was not curable, and its symptoms were devastating. Not only did it cause sores on the genitals, but it also led to ulcers that could eat into the bone, face, nose, and eyes. It led to blindness in many cases, and, as described by Pandarus, often caused crippling bone and joint pain.

There’s also some critical speculation on whether Shakespeare himself syphilis. He describes the symptoms of the disease in pretty vivid detail. One scholar, John Ross, notes that Shakespeare was heavily influenced by his contemporaries, but their treatments of venereal disease are dramatically different from Shakespeare’s. For example, Christopher Marlowe, whose “Jew of Malta” likely influenced Shakespeare’s Shylock in “The Merchant of Venice,” only includes six lines referencing venereal disease in his entire collection of plays. In contrast, Shakespeare alludes to syphilis in 61 lines in Troilus and Cressida alone. Though we can’t know whether or not he had the disease, Shakespeare at least demonstrates a degree of fascination with syphilis, mentioning it in several other plays including Measure for Measure and Timon of Athens, as well as some of his poems.

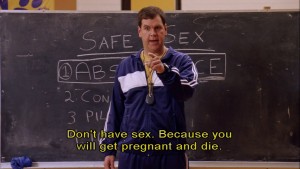

So there you have it. If reading Troilus and Cressida as an extremely black criticism of war, sexuality, political structure…or anything else really…has got you down, just think of Pandarus and the original sex ed instructor.

Troilus and Cressida Citation:

The Complete Pelican Shakespeare: Shakespeare, William, and A. R. Braunmuller. The Complete Works. New York: Penguin, 2002. Print. Troilus and Cressida. (p. 474-524).