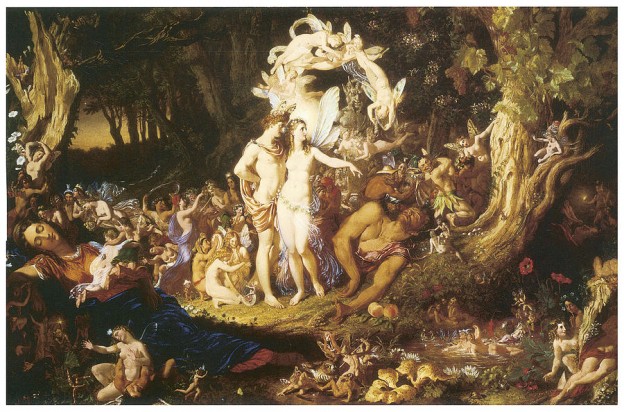

A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a play steeped in the fantastical: Shakespeare builds myth upon myth, creating a hodgepodge of mythical allusions to tell a story that seems completely trivial when compared to the weighty subjects of his other works. From the first scene, we are introduced to the Classical with the characters of Theseus and Hippolyta, and references to Greek and Roman mythologies can be found in abundance throughout every scene.

In the beginning of Act 2, Robin Goodfellow arrives, disrupting our Classical cast.

Those that Hobgoblin call you and sweet Puck, You do their work, and they shall have good luck: Are not you he?

Robin, also known as “puck,” belongs to Celtic folklore. His appearance paves the way for various other fantastical figures of various cultural origins: Oberon, king of the fairies, whose mythological origins stem from French pagan legends, and Titania, the fairy queen, who was invented by Shakespeare in allusion to Ovid’s Metamorphosis.

Amidst the noise of this mythological diffusion, the play follows the story of young lovers who become entwined with the fairy world. As the agent of their love, Shakespeare invokes an entity that is easily recognized today, by Classical scholars and schoolchildren alike: Cupid.

A not-so-blind Cupid

Today, the figure of Cupid survives in popular culture due to his association with Saint Valentine’s Day. Now, as in Shakespeare’s time, he is depicted as being armed with a bow and quiver. Today, however, his nature differs from his original metaphorical purpose: Cupid (or Cupido) means desire in Latin. In modernity, we tend to associate him more with true love rather than impulsive lust.

Although Cupid never actually appears in the play, his power has a vital influence on the plot. Using the juice of a flower struck by Cupid’s arrow, Oberon manipulates the minds of Titania, Lysander, and Demetrius in a game of matchmaking.

What does Cupid’s power to so easily sway the hearts of the characters say about the play’s notion of love? It seems to be conveying that love does not go much deeper than desire.

Helena states:

“Love looks not with the eyes, but with the mind; And therefore is wing’d cupid painted blind: Nor hath Love’s mind of any judgement taste; Wings and no eyes figure unheedy haste: And therefore is Love said to be a child, Because in choice he is so oft beguiled (I.1.237).”

Not a very flattering description of our arrow slinging friend. Later, Puck offers up a similar criticism:

“Cupid is a knavish lad, Thus to make poor females mad. (II.1.527)”

It seems like both human and supernatural beings of the play have issue with Cupid’s (and therefore love’s) “Knavery.” In the end, however, Cupid’s influence ends up working to Helena’s advantage when it causes Demetrius to finally fall in love with her. It’s a good turn out for Helena, and I guess Demetrius too, as long as he’s ok with living under a spell for the rest of his life… Which seems strange to modern audiences, mostly because our ideas of true love have changed since the days of arranged marriages. In Shakespeare’s time, when Cupid, the god of love, stood for desire, it may not have seemed so outlandish. By playing on the mythology of Cupid, staged amidst his creation of a mythological hodgepodge pastiche, Shakespeare provides commentary on the way love was being viewed, valued and assessed during his time.