The anniversary of the victory of the Nicaraguan Revolution is celebrated today much the same way as it was on July 19, 1979. Jubilant Sandinistas from across the country flood into Managua. Instead of celebrating at the Plaza de la República as they did in 1979, they gather at the larger Plaza de la Fe. Hundreds of thousands of Nicaraguans squeeze into the square and millions more watch on television. In the center of the plaza an obelisk honors Pope John Paul II’s two visits to Nicaragua. On one end there is a Concha Acústica (acoustic shell) that holds a stage for concerts. On Nicaraguan Liberation Day the stage in the Concha Acústica is used as a platform for public speeches.

In some ways, July 19th is celebrated like Independence Days in other countries with parades, speeches, even fireworks. However, it is explicitly political. The American Overseas Security Advisory Council (OSAC), which issues warnings to Americans traveling abroad, warned “U.S. citizens that even political rallies intended to be peaceful have the potential to escalate into violence. American citizens are therefore urged to exercise caution.” They classify Nicaraguan Liberation Day not as a public holiday but a political rally. By celebrating the victory of the Sandinista revolution, Daniel Ortega and the Sandinista party reaffirm their legitimacy as the purveyors of Nicaraguan freedom and prosperity. Anyone who opposes them is siding with the repression of the Somoza dictatorship.

This year Daniel Ortega invited Nicolas Maduro, the the leader of Venezuela, to the festivities. In his speech Ortega defended Maduro, who faced a referendum to remove his mandate from Venezuelan opposition. Ortega said Barack Obama’s “obsession” with Venezuela stemmed from a belief that “defeating Venezuela, destroying Venezuela, first affects the morale of the American people” and would boost votes for Hillary Clinton. He continued, “The battle (the elections) is not decided in Venezuela but it is decided in the US…Venezuela’s battle is decided in Venezuela, not in the US.” Ortega’s message is clear: opposition to Maduro is colluding with the enemy (the United States).

Across the world in Tokyo, the ambassador of Nicaragua in Japan—Ambassador Saúl Arana—led an event to commemorate the success of the revolution. Diplomats from Cuba, Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, the Dominican Republic, Uruguay and Venezuela attended along with Japanese scholars and journalists. Ambassador Arana summarized the Sandinista struggle and called for greater cooperation and solidarity amongst Latin American countries.

Nicaraguan Liberation Day is a moment of national unity and pride, a nationalistic celebration of freedom. Yet it is also a glorified, ginormous political rally. The Sandinista Party uses the anniversary of the revolution to publicize their accomplishments, promote their political agenda, and advertise Nicaraguan socialism to other Latin American countries.

Below is Daniel Ortega’s speech this year (2016) commemorating the revolution.

On July 19, 1979 the New York Times reported, “The Sandinist takeover of Managua came suddenly and almost peacefully in the wake of General Somoza’s resignation and flight into exile in Miami early Tuesday.” With morale destroyed after Somoza’s escape, the National Guard surrounded to Sandinista forces and on July 19th the rebels took over Managua. The New York Times described that “Excited crowds lined the streets of the capital as truckloads of young rebels, many of them dressed in olive green uniforms and carrying automatic rifles, drove around the city, waving the redand‐black Sandinist flag and firing shots into the air.” Civilians and guerrilla fighters flooded into the Plaza de la República—the center of Managua, since renamed Plaza de la Revolución—to celebrate. At long last the fighting was done and the Somoza regime gone forever.

On July 19, 1979 the New York Times reported, “The Sandinist takeover of Managua came suddenly and almost peacefully in the wake of General Somoza’s resignation and flight into exile in Miami early Tuesday.” With morale destroyed after Somoza’s escape, the National Guard surrounded to Sandinista forces and on July 19th the rebels took over Managua. The New York Times described that “Excited crowds lined the streets of the capital as truckloads of young rebels, many of them dressed in olive green uniforms and carrying automatic rifles, drove around the city, waving the redand‐black Sandinist flag and firing shots into the air.” Civilians and guerrilla fighters flooded into the Plaza de la República—the center of Managua, since renamed Plaza de la Revolución—to celebrate. At long last the fighting was done and the Somoza regime gone forever.

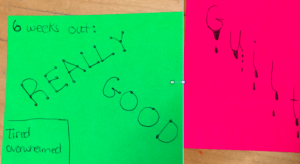

Kate, Leah, and Valentina discussed maternal mental health. With already limited access to healthcare, mental health is scarce in Nicaragua. For rural women this is particularly true, with 55% of women in rural regions giving birth at home. This group proposes beginning a conversation about mental health among mothers and allowing them to express (through words and drawings) their feelings. Mental health is part of a healthy lifestyle and should not be overlooked simply because there are other problems with the health system.

Kate, Leah, and Valentina discussed maternal mental health. With already limited access to healthcare, mental health is scarce in Nicaragua. For rural women this is particularly true, with 55% of women in rural regions giving birth at home. This group proposes beginning a conversation about mental health among mothers and allowing them to express (through words and drawings) their feelings. Mental health is part of a healthy lifestyle and should not be overlooked simply because there are other problems with the health system.