When I traveled to Nicaragua in 2013 with Amigos de las Américas almost everyone on the program was sick at some point—from contaminated water, Dengue, you name it. One girl was bitten by a dog and would have had to be evacuated to the United States for rabbis treatment if they had not been able to capture and observe the animal. I personally had to leave my community for the nearby city, Somoto, to be treated for a high fever and diarrhea. Twice. First we would go to a clinic to have our pee, poop, blood, etc. tested. Then we would go to a private doctor for a further examination. Used to the systemic, comprehensive, centralized healthcare of the United States it was an exhausting process to trek back and forth across the city. As Americans we were receiving the best healthcare possible but most of us never even received diagnoses. Healthcare in Nicaragua—particularly for the majority who cannot afford to pay for multiple inconclusive visits to clinics and doctors—is scarce and not thorough.

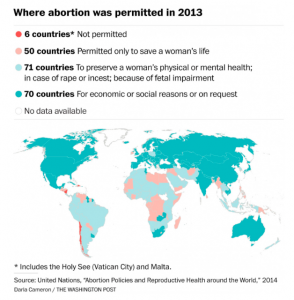

Which makes the consequences of Nicaragua’s abortion ban even more severe. In 2006 Daniel Ortega and the Sandinistas formed a political coalition with the Catholic Church and enacted a total ban on abortion, even for rape victims and when the woman’s safety is in danger. According to the United Nations, in 2013 only six countries in the world did not permit abortions under any circumstances. Obviously this has many consequences. Rape victims are forced to not only undergo the emotional trauma of their violation but also have their rapist’s child. Young girls (and, as Catholics for the Right to Choose stated in an ad campaign, “All pregnant children were raped) lose their childhood and are forced to prematurely take on adult responsibilities. Illegal, unsafe abortions lead to maternal deaths.

Which makes the consequences of Nicaragua’s abortion ban even more severe. In 2006 Daniel Ortega and the Sandinistas formed a political coalition with the Catholic Church and enacted a total ban on abortion, even for rape victims and when the woman’s safety is in danger. According to the United Nations, in 2013 only six countries in the world did not permit abortions under any circumstances. Obviously this has many consequences. Rape victims are forced to not only undergo the emotional trauma of their violation but also have their rapist’s child. Young girls (and, as Catholics for the Right to Choose stated in an ad campaign, “All pregnant children were raped) lose their childhood and are forced to prematurely take on adult responsibilities. Illegal, unsafe abortions lead to maternal deaths.

The impact of this law within the healthcare system is also devastating. Nicaraguans already receive less and worse care than most Americans. With the abortion ban, doctors are afraid to treat pregnant women for fear they may harm the fetus and face legal consequences. And they have a right to be. According to the Nicaraguan penal code: “Whosoever, by whatever method or procedure wounds the unborn or causes an illness which has grave consequences for normal development, or causes a grave and permanent physical or psychological wound will be punished by between two to five years in prison and a prohibition on exercising any medical profession or providing services of any type in a clinic or gynaecological practice, public or private, for between two and eight years.” The wording of the code—”whosoever, by whatever method or procedure”—clearly states that doctors could be prosecuted for saving a woman’s life at the expense of their fetus.

The care a pregnant woman receives thus entirely depends on how much personal risk an individual doctor is willing to take. Will the doctor provide the best care and risk the consequences? Or avoid care that could harm the fetus even when it would save the mother? According to Amnesty International, “Treatment for obstetric complications has become a lottery” because the healthcare provided depends on the doctor rather than standards for best practice. Even when pregnant women are able to access healthcare services, they thus may not receive the care they need.

During a research mission to Nicaragua in 2007, the Human Rights Watch documented the consequences of such harmful delays in care. They also interviewed government and health officials who admitted concern about the impact of the abortion ban on women’s health. Below are narratives from their report that illustrate the devastating consequences.

Excerpts from the 2007 Human Rights Watch report on Nicaragua’s abortion ban:

“She was bleeding … That’s why I took her to the emergency room … but the doctors said that she didn’t have anything. … Then she felt worse [with fever and hemorrhaging] and on Tuesday they admitted her. They put her on an IV and her blood pressure was low. … She said: ‘Mami, they are not treating me.’ … They didn’t treat her at all, nothing. … When her husband came to bring her food, he heard screams. … They took her to [another hospital in Managua], but it was too late. She died of cardiac arrest. … She was all purple, unrecognizable. It was like it wasn’t my daughter.”

— Angela Morales [real name withheld], mother of a 22-year-old woman who died from pregnancy-related hemorrhaging at public hospital in Managua in November 2006, only days after the blanket ban on abortion was implemented. From comments made by the doctors at the time, Morales believes her daughter was left untreated because doctors were reluctant to treat a pregnancy-related emergency for fear that they might be accused of providing therapeutic abortions

“The effect [of the ban] has been in the medical personnel. … There have been situations that should have been treated [but] out of fear they haven’t been treated fast. … For example, in one hospital we have a patient with an ectopic pregnancy, it was ruptured, there was nothing to do [to save the fetus] but [the patient] was not treated. … It’s like an excuse. … The doctors don’t want to put themselves on the line. … We have received complaints.”

— Dr. Jorge Orochena, Director for Quality Control, Health Ministry