- Background and Historical Context

- Significance

- Core Challenges

- Possible Interventions

- Exemplars

- Additional Readings and Resources

Abstract

On April 25 and May 12, 2015 two large earthquakes of magnitudes 7.8 and 7.3 respectively struck Nepal. Malnutrition, especially among women and children under the age of five, was prevalent before the earthquakes. At the same time, transportation was difficult between agricultural communities due to geographical separation.The earthquakes severely damaged agricultural supplies, stored food stocks, transportation infrastructure, and shelters. This has increased malnutrition rates particularly in Nepal, particularly affecting women and young children. Malnutrition can have adverse health affects, and can be detrimental to a nations development. This study focused on sustainable agricultural interventions and immediate aid specifically targeting rural communities. Some of these interventions include providing therapeutic food supplements, seeds for replanting, and livestock. Many organizations are enacting different interventions in Nepal. Yet, this study focuses on several organizations that have partnerships with various governments and receive funding from private sources.

Background and Historical Context

Pre-Quakes:

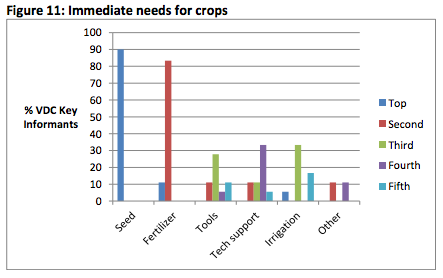

Nepal is a poor rural nation with a Human Development Index of .463, ranking it at 157th out of 187 nations (Rural poverty in Nepal). The overall poverty rate in Nepal was 25 percent. Agriculture constitutes the mainstay economy in Nepal. It employs approximately 75 percent of the labor force as of 2010, and constitutes more than a third of Nepal’s GDP (Nepal Economy Profile 2014) Also, estimates of the number of agriculturally based families in Nepal range from approximately 75 to 85 percent [1].

Figure 1: Breakdown of Nepal’s Economy by Sector

Approximately 84 percent of Nepalese live in rural areas and depend on subsistence agriculture for their livelihoods and to provide food for themselves [2]. In order to do this Nepalese need livestock, seeds, and a sufficient amount of land. Livestock have traditionally played an important, and multi-purpose role in Nepalese agriculture. Roughly 87 percent of households in Nepal keep some form of livestock [3]. Livestock are used as beasts of burden and are important in fertilizing fields. Few small landholders can afford to buy chemical and mineral fertilizers, making manure from livestock a vital form of returning nutrients to the soil [4]. Also, livestock contribute to the Nepalese diet. In 2002 the per-capita consumption of milk was 30kg a year and the per-capita consumption of meat was 10kg a year [5]. Thus, livestock are very important to food security and adequate nutrition in Nepal.

The typical Nepalese diet consist mostly of rice, potatoes, and legumes. Animal products are not frequently consumed, particularly among poor populations. Also, women typically consume fewer animal products than men [6]

Seeds for replanting fields are either purchased or saved from a previous harvest [7]. Nepalese usually store seeds within their homes. Without supplies to replant fields, people in rural Nepal would face economic hardship and food scarcity. Yet, these seeds are often of outdated varieties, with low purity and germination rates [8]. These varieties are susceptible to pests and diseases as well [9].

Agricultural production in Nepal is among the lowest in South East Asia [10]. In remote, rural areas of Nepal local food production barley meets consumption. Thus, many rural people are dependent on buying food and external aid. This is true for the nation of Nepal as well. Prior to the earthquake Nepal did not produce enough food to satisfy domestic consumption. As a result Nepal imports food to meet domestic demand, in 2010 it imported 316,000 metric tons of food, which was a 139 percent increase from the year before [11].

All of this contributed to malnutrition before the quakes, especially among children under the age of five and women. In 2010 the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) reported that Nepal’s Global Hunger Index (GHI) ranked it 54th out of 56 nations it studied [12]. In this time period approximately 16 percent of the population was malnourished and 38.8 percent of children under five were underweight. Also, 4.8 percent of these children died before the age of five as a result of under nourishment [13]. Furthermore, the food scarcity is Nepal is worse in more remote and rural areas, but there is not a single region of the country that falls into or above the IFPRI’s moderate or low- hunger categories [14]. Approximately nine million Nepalese were venerable to food scarcity before the quake and sub-populations like young children and women in rural areas are particularly affected [15]. That means about half of Nepal’s population was undernourished before the quakes, and, nearly 50 percent of children under five were chronically malnourished, as were 18 percent of women between the ages of 15 and 49 [16].

Post-Quake:

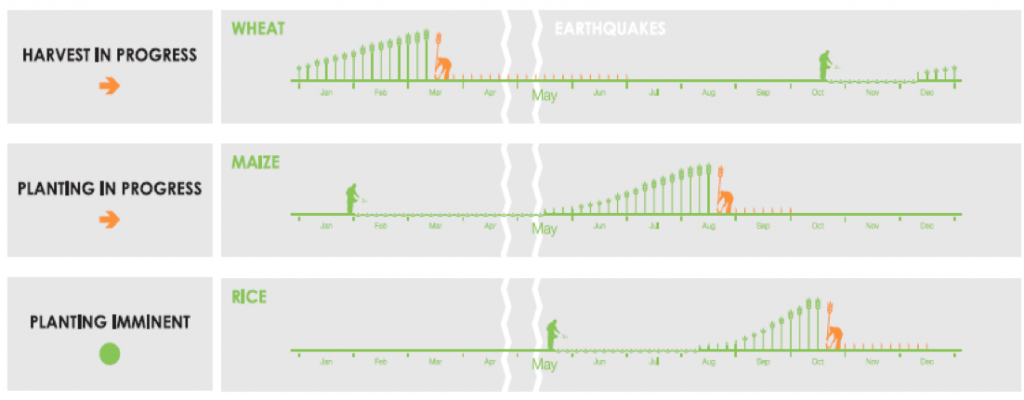

A report by the World Health Organization (WHO) stated: “The populations affected by the earthquake will be at increased risk of moderate and severe acute malnutrition if there is a lack of access to appropriate and adequate food”, it continued to report that, “this will disproportionately affect vulnerable groups such as young children” and women [17]. Unfortunately the earthquakes and their aftershocks have created a situation where the rural population of Nepal does not have access to adequate food supplies, in part due to the earthquakes’ affects on agriculture and roads. Six districts that were severely affected by the quakes are Dhading, Dolakha, Gorkha, Nuwakot, Rasuwa and Sindhupalchock (Nepal Earthquake). In these districts and elsewhere in Nepal the earthquakes had a large impact on crop production and especially stored crops and seeds. The timing of the first quake was amid important agricultural activities (Figure 2).

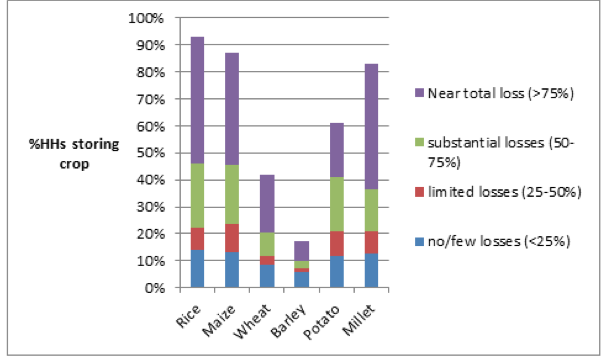

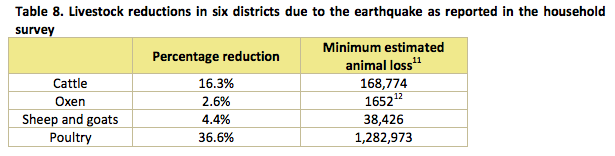

The greatest impact of the timing of this quake in regards to malnutrition and agriculture is that it occurred just a few weeks before rice, the main staple crop in Nepal, was planted. This means the rice reserves in rural communities that were being kept in storehouses and about to be planted when the quakes struck, were lost. Many households in rural districts experienced near total losses of stored rice, maize, wheat, potato, and millet (Figure 3). For rice, maize and millet approximately 40 percent of households incurred a near total loss [19]. Initial standing crop losses are not high, but they are expected to increase due to lack of means to harvest them, and inadequate storage facilities for harvested crops [21]. Also, contributing to food scarcity in rural Nepal is the Earthquakes effects on livestock.Livestock were commonly kept under houses, tied next to houses, or near a family’s dwelling. As a result when the earthquakes struck many animals were killed. The Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations reported that 20 percent of cattle and 42 percent of poultry in Gorkha, Rasuwa, Nuwakot, Dhading, Dolakha, Sindhupalchock, Kabhrepalanchok, Ramechhap, Okhaldhunga, Sindhuli and Makawanpur (some of the hardest hit rural districts) died in the earthquakes [22]. Also, many more have died due to injuries and illnesses as a result of the quakes. This caused a significant reduction in the amount of fertilizer available to rural agricultural households in Nepal and a large reduction of animal product consumption (Figure 4) [23].

Significance

As of May 25, 2015 approximately 70,000 children under the age of five were at risk of malnutrition and required immediate aid. Of these 15,000 were suffering from severe acute malnutrition and required therapeutic foods, and 55,000 had moderate acute malnutrition [24]. These numbers have most likely increased since May 25th and now even more children in Nepal are likely suffering from severe and moderate malnutrition, and their related illnesses [25].

Furthermore, malnutrition can severely limit economic growth and can perpetuate poverty. The World Bank estimates that malnutrition costs poor nations 3 percent of their yearly GDP. Also, Jean-Louis Sarbib, Senior Vice President for Human Development at the World Bank stated, “Poor nutrition is implicated in more than half of all child deaths worldwide—a proportion unmatched by any infectious disease since the Black Death” [26].

Poverty is both an outcome and a cause of malnourishment and poor human development. Children who are malnourished from while between the ages of 0-5 have inhibited cognitive abilities and are less likely to stay in school than well-nourished children. Also, malnourishment in early childhood has negative affects on adult earnings and productivity later in life. These two phenomena caused by malnourishment are linked. Each additional year of schooling is approximately equal to a 12-14 percent increase in lifetime earnings [27]. Also, indivgduals’ earnings are tied to national development. If individuals have more money then they can spend more, thus stimulating a nations economy. Furthermore, wealth is linked to good health. Countries with high GDP per capita also have high life expectancies for individuals (Figure 5). This is in part because a high GDP per capita means that more money is stimulating a nation’s economy, and that governments will have more money to spend on public health [28]. Thus, malnourishment among women and children under five can inhibit Nepal’s development and the quality of its public health.

Core Challenges

Inaccessibility and Providing Aid

Traditionally, Nepali households store their food items and harvests in their homes. When earthquakes strike, houses collapse, leaving families without supplies or places for storage. Therefore, they experience food shortages. This is heightened by the fact that many households are far from markets, and by the fact that landslide rubble may lie on the only route to and from the villages making transportation of aid extremely difficult. Many of the villages affected by the earthquakes are in remote, and inaccessible areas of Nepal. This inaccessibility becomes extremely problematic in the long run, especially after the earthquakes have caused these areas to be even more inaccessible [30]. Isolated households and villages are put at extreme risk when disasters hit, because it makes the travel very difficult for people needing to reach health facilities, and for varies forms of aid to reach people in need. This particularly affects vulnerable populations like women and young children. For pregnant and nursing women with young children, its extremely crucial to have access to health care clinics / hospitals near their home, in case of emergency. Increased inaccessibility to already remote areas, as a result of the earthquake, has made it more difficult to restock agrarian households with agricultural supplies such as seeds, livestock, and tools [31].

Shelters for People and Livestock

The existing levels of international assistance for Nepal’s earthquake-affected farmers are estimated to be delivering only a fraction of the assistance required. To this day, several earthquake survivors live under corrugated iron shelters, tarpaulins, and even plastic tunnels that are normally used for growing vegetables. These temporary shelters are problematic because they are vulnerable to mudslides. This is problematic to pregnant and nursing women because they do not have a place to give birth to their child, or if they do it is extremely unsanitary an exposes both the mother and the child to infection. Additionally, many farmer’s animals are without shelter as well making them more prone to disease and predation [32].

Supplements

Uncontrolled donations of infant formula and other breast-milk substitutes can increase deaths and morbidity rates among infants and young children. This is because newborns are exclusively breastfed for the first six months of their life, and the switch to a breast milk substitutes weakens their immune system. The risks for malnutrition may be increased by the lack of support for mothers or caretakers to breastfeed their children. If mothers refuse to feed their children naturally and turn to alternative methods for feeding, it will negatively affect young children. Infants require breastfeeding within one hour of birth and it is recommended that they continue to breastfeed exclusively until they are 6 months old. This means that they are not allowed to consume any other type of food or liquid (including water) besides breast milk. The goal is to design and maintain a breastfeeding comfortable environment for the child until about two years of age. Otherwise, the child may be prone to certain infections and diarrhea [33]. This issue illustrates some of the core challenges because although relief efforts are being made to supply food and sustenance to malnourished children and pregnant or nursing women, these efforts cause other infections and health issues in the target population. Therefore, although organizations may think they are helping the problem of malnutrition, they are creating other problems in the process.

Possible Interventions

One possible intervention is to supply people with access to food. Another possible interventions to provide agricultural supplies to communities. This would prove to be beneficial in the upcoming months when aid is no longer sufficient, and it will allow farmers to revitalize their fields to sustain their families [34].

Immediate Aid: Food Supplements

Populations dependent on food aid need to be given food rations that are safe and adequate in terms of quantity and quality, which includes: covering macro- and micro-nutrient needs [35]. Food supplements to pregnant or nursing mothers are highly encouraged. The mothers need to maintain a well-nourished diet in order to keep themselves and their child from being malnourished. This clashes with the cultural norms in that women and girls traditionally eat last in the family. The problems are exasperated when natural disasters like earthquakes create food insecurity and scarcity. It is imperative that women receive adequate nutritional intake so that they are able to provide healthy breast milk. Ready to use therapeutic foods and supplements would reduce malnutrition and anemia, and would provide an incentive for women to visit pre-natal clinics [36]. Infants 6 months old and up need hygienically prepared, easy-to-eat, and digestible foods that nutritionally complement breast milk [37].

Sustainable: Agricultural Supplies (Seeds, Livestock, and Tools)

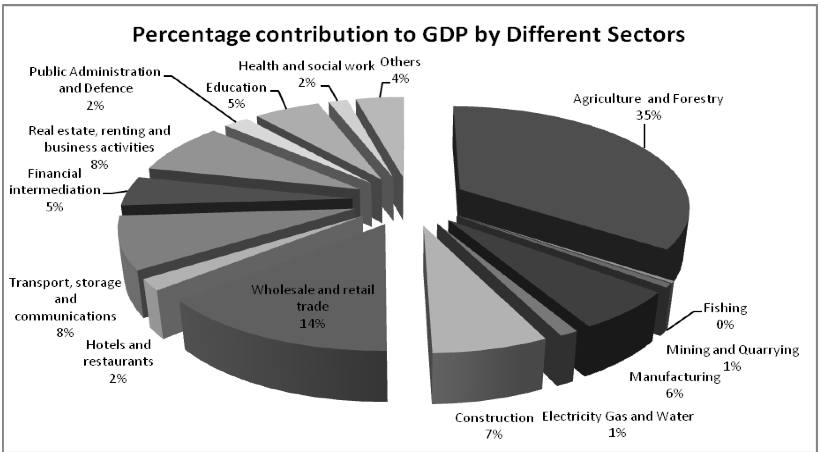

For any responders to the agricultural deficit, cash and voucher transfers are encouraged for providing lots of families with fertilizers, tools, and livestock. Overall, a program or organization’s implementation arrangements will be successful only if they align with the government’s overall priorities for the agriculture sector [38]. Being that livestock are a continuous supply of food, labor, and fertilizers it is crucial to preserve their livelihood. If a farmer does not preserve his animals, they are not easy to replace. Further livestock losses can be prevented with timely veterinary supplies, feed, and shelter. Another possible intervention is supplying fresh livestock to households in agricultural communities.

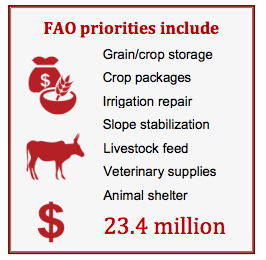

It is critical that farmers find immediate grain storage to prevent further losses of their 2015 wheat crop and other crops. Beginning in October, farmers will also need storage capacity for harvested rice. Provisions of vegetable seeds need to be made in order to increase access to nutrient-rich foods. One needed intervention is the replenishing seed stores that were lost. This is also an opportunity to provide new more resilient and productive varieties of crops. In order for these distributions to occur rapidly, it is crucial that organizations work with the existing government in Nepal and coordinate their efforts to restore rural livelihoods and food production [39]. In the long-term recovery scheme, interventions should aim at developing larger networks of crop diversification as well as the adoption of good agricultural practices (preservation of food storages, restocking tool supply, etc) [40].

Exemplars

Immediate Aid: Food Supplements

Post-earthquake the first priority was providing food, shelter and medical care. As mentioned previously Nepal before the earthquake had many children at risk of malnutrition. Due to the earthquake the risk has become a reality for approximately 70,000 children. In the past few months, UNICEF a sector of the United Nations, has been working to get therapeutic foods to children and breastfeeding mothers in Nepal. Breastfeeding children are especially at risk of malnutrition because mothers fear that their child will become sick from their milk. UNICEF has devised a plan in which they not only bring in therapeutic foods for mothers and young children, but have been broadcasting through radio the importance of breastfeeding vs. formula. The help UNICEF is providing is very important for immediate aid, but with a disaster like this, it is important to look ahead ensure that the country will be able to sustain itself once the immediate aid is no longer available.

Sustainable: Agricultural Supplies (Seeds, Livestock, and Tools)

Heifer International is a non-profit NGO based out of Arkansas that focuses on helping communities around the world. They work to provide people with sustainable food production while taking into consideration local markets. Since 1957 Heifer International has been working with Nepal sending in cattle, pigs and poultry. [41]

In the recent Nepal earthquake Heifer International focused first on providing immediate aid and donated emergency relief supplies including tarps, mattress rolls and blankets. As of June, Heifer shifted to sending in supplies for sustainable relief. They have been helping reconstruct shelters for animals, storage for food supplies and donating different types of livestock. On their website one can currently “purchase” a goat, cow, or water buffalo that will go to a family in need. These animals are great for sustainable farming because they provide labor for farming, fertilizer for the crops and goods such as milk, eggs and cheese that can not only feed the family but be sold and incorporated into the local market.

Heifers money comes from the government, their partnerships with different donor agencies (Starbucks, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation) and people like us looking to help.

Seeds Program International (SPI) is another NGO that seeks to provide people with seed expertise and training materials for sustainable farming. Earlier in the year SPI was raising funds to send help to Nepal, but unfortunately they had some complications with taxes and the Nepal government. Nonetheless their work is important to mention because of its focus on sustainable aid. SPI similar to Heifer International takes into consideration the long term problems a community post-disaster must face. Providing seeds and training materials helps feed communities and stimulate local commerce. [42]

OXFAM is a charity based in England that focuses on helping people in poverty. For the Nepal earthquake they sent in emergency supplies including clean water, toilets, hygiene kits, emergency shelter, food and seeds. Again, seeds are vital in this equation, and OXFAM recognizes the long-term issues Nepal will face [43]. Before the earthquake OXFAM was also involved in women empowerment and seed trade in Nepal. The following video is from December 2013 [44].

Additional Readings and Resources

If interested in more information you can following the links below:

- A case study by the FAO of the Nepal Earthquake, describes in detail the impact has had on farming, the crops and the tools.

- This is a study from 2011 that explains the problems with food security and how it has led to malnutrition in Nepal.

- This scientific article goes in depth about the issues that arise with Maternal and child undernutrition, although it doesn’t analyze Nepal specifically it looks at undernutrition through a medical and social lens.

- This an executive brief by the FAO and it gives a summary of the importance of timing in crops and how the earthquake has impacted the crops this year specifically.

Discussion Questions

- At what point should a charity stop administering emergency aid and start administering sustainable aid?

- How do you keep people engaged and up to date on the needs of people in natural disasters past the initial shock?

- With limited resources from foreign aid flowing into Nepal’s earthquake rocked areas, how do you think aid should be distributed? Should it be distributed to the least affected so they can rapidly become the most productive or to the most affected to try and restore them to previous levels of productivity?

- How would you go about providing more productive crops to Nepalese people, keeping in mind that new forms of crops would alter the foods they eat which are culturally prescribed?

References

- “Livestock Sector Brief: Nepal.” Sector Briefs (2005): 1-18. United Nations. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2005. Web. 13 Aug. 2015. <http://www.fao.org/ag/againfo/resources/en/publications/sector_briefs/lsb_NPL.pdf>.

- “Rural Poverty Portal.” Rural Poverty Portal. International Fund for Agricultural Development, n.d. Web. 16 Aug. 2015. <http://www.ruralpovertyportal.org/country/home/tags/nepal>.

- “Analysis: Why Livestock Matters in Nepal.” IRINnews. IRIN News, 2015. Web. 16 Aug. 2015.

- “The Importance of Livestock.” The Importance of Livestock. World Bank, n.d. Web. 13 Aug. 2015. <http://www.worldbank.org/html/cgiar/newsletter/Sept97/10ilri.html>

- “Livestock Sector Brief: Nepal.” Sector Briefs (2005): 1-18. United Nations. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2005. Web. 13 Aug. 2015. <http://www.fao.org/ag/againfo/resources/en/publications/sector_briefs/lsb_NPL.pdf>.

- Campbell, Rebecca K., Sameera A. Talegawkar, Parul Christian, Steven C. LeClerq, Subarna K. Khatry, Lee S.F. Wu, and Keith P. West. “Seasonal Dietary Intakes and Socioeconomic Status among Women in the Terai of Nepal.” Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition. International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh, 2014. Web. 23 Aug. 2015. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4216957/>.

- “Nepal Earthquake: Agricultural Livelihood Impact Appraisal in Six Most Affected Districts.” Food Scarcity Cluster (2015): 1-53. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 6 June 2015. Web. 13 Aug. 2015. <http://foodsecuritycluster.net/sites/default/files/Nepal%20ALIA%20-%20Agricultural%20Livelihoods%20Impact%20Appraisal%20-%20June%2006_0.pdf>.

- “Food and Nutrition Security in Nepal: National Status from the Perspectives of Civil Society.” Asian NGO Coalition for Agrarian Reform and Rural Development (ANGOC) for the Alliance against Hunger and Malnutrition (AAHM) (2012): 1-10. Angoc. Agrarian Reform and Rural Development, July 2012. Web. 16 Aug. 2015. <http://www.angoc.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/12/food-and-nutrition-security-in-nepal-national-status-from-the-perspectives-of-civil-society/Nepal_Paper_Status_of_Food_Security.pdf>

- “Food and Nutrition Security in Nepal: National Status from the Perspectives of Civil Society, 1-10.

- “Food and Nutrition Security in Nepal: National Status from the Perspectives of Civil Society, 1-10.

- Shively, Gerald, Jared Gars, and Celeste Sununtnasuk. “A Review of Food Security and Human Nutrition Issues in Nepal.” Purdue University Department of Agricultural Economics Staff Paper (2011): 1-51. edu. Department of Agricultural Economics Purdue University, 28 Sept. 2011. Web. 13 Aug. 2015. <http://www.agecon.purdue.edu/staff/shively/Nepal_review.pdf>.

- Shively, “A Review of Food Security and Human Nutrition Issues in Nepal.”, 1-51.

- Shively, “A Review of Food Security and Human Nutrition Issues in Nepal.”, 1-51.

- Shively, “A Review of Food Security and Human Nutrition Issues in Nepal.”, 1-51.

- Shively, “A Review of Food Security and Human Nutrition Issues in Nepal.”, 1-51.

- “Adolescent Nutrition: A Review of the Situation in Selected South-East Asian Countries.” Adolescent Nutrition: A Review of the Situation in Selected South-East Asian Countries (2006): Iiv-84. who. World Health Organization, Mar. 2006. Web. 17 Aug. 2015. <http://apps.searo.who.int/PDS_DOCS/B0239.pdf>.

- “Humanitarian Crisis after the Nepal Earthquakes 2015.” World Health Organization: Nepal (2015): 1-32. who. World Health Organization, May 2015. Web. 17 Aug. 2015. <http://www.searo.who.int/entity/emergencies/phra_nepal_may2015.pdf>.

- “Nepal Earthquake: Agricultural Livelihood Impact Appraisal in Six Most Affected Districts.” Food Scarcity Cluster (2015): 1-53.

- “Nepal Earthquake: Agricultural Livelihood Impact Appraisal in Six Most Affected Districts.” Food Scarcity Cluster (2015): 1-53.

- “Nepal Earthquake: Agricultural Livelihood Impact Appraisal in Six Most Affected Districts.” Food Scarcity Cluster (2015): 1-53.

- “Nepal Earthquake: Agricultural Livelihood Impact Appraisal in Six Most Affected Districts.” Food Scarcity Cluster (2015): 1-53.

- “Nepal Earthquake: Agricultural Livelihood Impact Appraisal in Six Most Affected Districts.” Food Scarcity Cluster (2015): 1-53.

- “Nepal Earthquake: Agricultural Livelihood Impact Appraisal in Six Most Affected Districts.” Food Scarcity Cluster (2015): 1-53.

- “Nepal Earthquake: Agricultural Livelihood Impact Appraisal in Six Most Affected Districts.” Food Scarcity Cluster (2015): 1-53.

- “Nepal Earthquakes: One Month on from First Quake, Malnutrition a Growing Threat for Children – UNICEF.” UNICEF. United Nations, 2015. Web. 17 Aug. 2015. <http://www.unicef.org/media/media_82046.html>.

- “Nepal Earthquakes: One Month on from First Quake, Malnutrition a Growing Threat for Children – UNICEF.”, United Nations, 2015.

- Hay, Phil, and Olivia Elee. “Malnutrition Causes Heavy Economic Losses, Contributes to Half of All Child Deaths, But Can Be Prevented-New World Bank Report.” Nutrition. World Bank, 2011. Web. 13 Aug. 2015. <http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/TOPICS/EXTHEALTHNUTRITIONANDPOPULATION/EXTNUTRITION/0,,contentMDK:20839585~menuPK:282580~pagePK:64020865~piPK:149114~theSitePK:282575,00.html>.

- Victora, Cesar G., Linda Adair, Caroline Fall, Pedro C. Hallal, Reynaldo Martorell, Linda Richter, Harshpal Singh Sachdev, and For the Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group. “Maternal and Child Undernutrition: Consequences for Adult Health and Human Capital.” Lancet. Lancet Publishing Group, Jan. 2008. Web. 17 Aug. 2015. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2258311/>.

- Deaton, Angus. “Health, Inequality, and Economic Development.” Journal of Economic Literature1 (2001): 113-58. JSTOR [JSTOR]. Web. 17 Aug. 2015. <http://www.princeton.edu/rpds/papers/Deaton_Health_Inequality_and_Economic_Development_JEL.pdf>.

- “GDP per Capita vs. Life Expectancy.” Google Public Data. World Bank, Google, 27 July 2015. Web. 18 Aug. 2015. <http%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2Fpublicdata%2Fexplore%3Fds%3Dd5bncppjof8f9_%26ctype%3Db%26strail%3Dfalse%26nselm%3Ds%26met_x%3Dsp_dyn_le00_in%26scale_x%3Dlin%26ind_x%3Dfalse%26met_y%3Dsp_dyn_tfrt_in%26scale_y%3Dlin%26ind_y%3Dfalse%26met_s%3Dsp_pop_totl%26scale_s%3Dlin%26ind_s%3Dfalse%26dimp_c%3Dcountry%3Aregion%26ifdim%3Dcountry%26iconSize%3D0.5%26uniSize%3D0.035%23!ctype%3Db%26strail%3Dfalse%26bcs%3Dd%26nselm%3Ds%26met_s%3Dsp_pop_totl%26scale_s%3Dlin%26ind_s%3Dfalse%26dimp_c%3Dcountry%3Aregion%26met_x%3Dny_gdp_pcap_kd%26scale_x%3Dlin%26ind_x%3Dfalse%26met_y%3Dsp_dyn_le00_in%26scale_y%3Dlin%26ind_y%3Dfalse%26ifdim%3Dcountry%26hl%3Den_US%26dl%3Den_US%26ind%3Dfalse>.

- “Reviving Agriculture in Rural Areas of Earthquake-hit Nepal.” Reviving Agriculture in Rural Areas of Earthquake-hit Nepal. Agency for Technical Cooperation and Development, 22 July 2015. Web. 20 Aug. 2015. http://www.preventionweb.net/english/professional/news/v.php?id=45201.

- “Analysis: Why Livestock Matters in Nepal.” IRINnews. N.p., 18 Aug. 2015. Web. 18 Aug. 2015. <http://www.irinnews.org/report/98463/analysis-why-livestock-matters-in-nepal>.

- “FAO In Emergencies.” Nepal Earthquakes (2005): 1-18. United Nations. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2005. Web. 13 Aug. 2015. http://www.fao.org/emergencies/crisis/nepal-earthquakes/intro/en/

- “Veterinary Relief Efforts Begin after Nepal Earthquake.” Veterinary Record 176.19 (2015): 22-23. Humanitarian Crisis after the Nepal Earthquakes 2015. World Health Organization. Web. 16 Aug. 2015.<http://www.searo.who.int/entity/emergencies/phra_nepal_may2015.pdf>.

- “Reviving Agriculture in Rural Areas of Earthquake-hit Nepal.” Reviving Agriculture in Rural Areas of Earthquake-hit Nepal. Agency for Technical Cooperation and Development, 22 July 2015. Web. 20 Aug. 2015. http://www.preventionweb.net/english/professional/news/v.php?id=45201.

- “Veterinary Relief Efforts Begin after Nepal Earthquake.” Veterinary Record 176.19 (2015): 22-23. Humanitarian Crisis after the Nepal Earthquakes 2015. World Health Organization. Web. 16 Aug. 2015. <http://www.searo.who.int/entity/emergencies/phra_nepal_may2015.pdf>.

- “Nepal Earthquakes: One Month on from First Quake, Malnutrition a Growing Threat for Children – UNICEF.” UNICEF. United Nations, 2015. Web. 17 Aug. 2015. <http://www.unicef.org/media/media_82046.html>.

- “Veterinary Relief Efforts Begin after Nepal Earthquake.” Veterinary Record 176.19 (2015): 22-23. Humanitarian Crisis after the Nepal Earthquakes 2015. World Health Organization. Web. 16 Aug. 2015. <http://www.searo.who.int/entity/emergencies/phra_nepal_may2015.pdf>.

- “Great Earthquakes.” SpringerReference (2011): 1-2. FAO, 29 June 2015. Web. 16 Aug. 2015. <http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/FAO%20Executive%20Brief%20_%20Nepal%20Earthquake_29%2006%2015.pdf>.

- “Great Earthquakes.” SpringerReference (2011): 1-2. FAO, 29 June 2015. Web. 16 Aug. 2015. <http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/FAO%20Executive%20Brief%20_%20Nepal%20Earthquake_29%2006%2015.pdf>.

- “Nepal Earthquakes: One Month on from First Quake, Malnutrition a Growing Threat for Children – UNICEF.” UNICEF. United Nations, 2015. Web. 17 Aug. 2015. <http://www.unicef.org/media/media_82046.html>.

- “Nepal Earthquake Appeal | Oxfam GB.” Oxfam GB. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Aug. 2015.

- “Where SPI Seeds Come From.” – Seed Programs International. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Aug. 2015.

- “Nepal: Four Months Post Earthquake | Heifer International | Charity Ending Hunger And Poverty.” Nepal: Four Months Post Earthquake | Heifer International | Charity Ending Hunger And Poverty. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Aug. 2015.