- Abstract

- Background and Historical Context

- Significance

- Core Challenges

- Possible Interventions

- Exemplars

- Additional Readings and Resources

- Discussion Questions

- References

Abstract

On April 25th, 2015, 15,000 [16] children lived in child care homes in Nepal, more than 80% of the country [4] relied on subsistence farming and only 59.8% of females were literate [2]. Needless to say, Nepal could already safely be characterized as vulnerable when a 7.8 magnitude earthquake devastated the country. In addition to Nepal’s perceptible vulnerabilities, a structurally violent and patriarchal society persists that put women and girls at a specific disadvantage in terms of finding economic opportunity and avoiding exploitation. The combination of structural and economic weakness and the proximity to the Indian border has created a major, yet hidden, trafficking system, that provides ample opportunities for traffickers to sneak women across the border. The recent earthquake is impactful not only due to the lives it took, but also the additional vulnerability that it has inflicted on the Nepali population. Nepal desperately needs to prioritize human trafficking prevention, which has proved to be difficult, if not impossible, at a time when countless other issues seem to be considered more urgent and important. In this case study, we hope to explore the historical and cultural context of human trafficking in Nepal, while identifying the unique challenges and potential or existing interventions that could aid human trafficking prevention efforts in a post-earthquake world.

In what ways is Nepal the “perfect storm” for human trafficking to remain a pervasive practice as the aftermath of the 2015 earthquakes unfolds?

As a final note, we have drawn the large majority of our data from two specific time periods, the first being the late 1990s and the second being the past three months. The late 20th century was a time in which the few trafficking acts that exist passed, which led to a unprecedented amount of literature on the subject. Since then, there has been very little effort to document or quantify the impacts of trafficking, until the April 2015 earthquake, which brought about the realization of the potential plight of trafficking to come.

Background and Historical Context

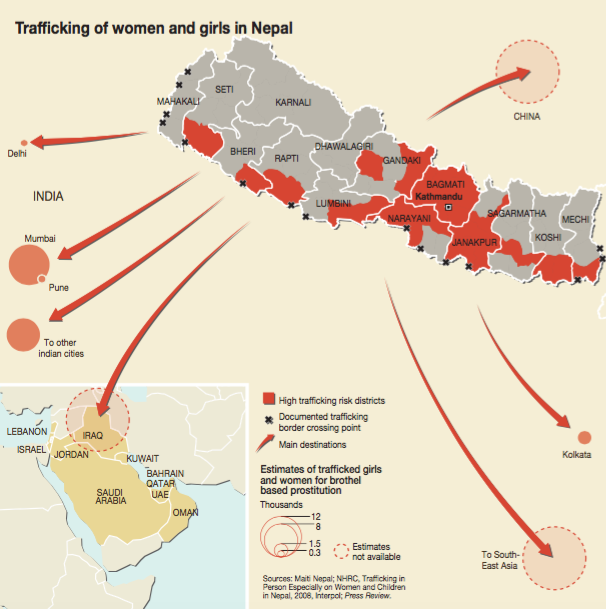

Human trafficking has had a pervasive presence in our world, although often disclosed and unseen due to the nature of secrecy surrounding the practice. Nepal seems to be disproportionately affected by human trafficking, as 20,000 women and girls [12] are smuggled across the border every year. When looking at the specificity of trafficking in Nepal, one must attend to the broader social, political, cultural and economic undercurrents in the country. These structures of violence impact all Nepalis in profound ways, but often tend to disproportionately impact women, which then lends significance to our discussion of trafficking.

This map estimates centers of trafficking, as well as popular paths taken out of Nepal by traffickers [5].

Poverty. Homelessness. Orphaned children. Lost livelihood. A perfect storm for human trafficking. http://t.co/yohaCTWzt4

— Pon Angara (@barkadacircle) August 8, 2015

[23]

Although we unfortunately live in a world in which women are second-class citizens in many countries, Nepal gender dynamics are an extreme case of what remains to be a patriarchal society. In 2004, only 61% of girls were enrolled in school while 80% of boys were, and only 23% of women could read while 57% of men could [11]. This investment in male offspring stems from the fact that sons are more likely to contribute economically to their families later in life, while women will be responsible for their own families.

In the wake of the #Nepal tragedy, the poor are even more vulnerable to #trafficking. How can we protect our sisters? http://t.co/YreGfOQWuR

— Mallory Moench (@mallorymoench) August 17, 2015

[24]

The aforementioned ways that women are positioned in society must be understood when looking at the reasons as to why they are the victims of the majority of human trafficking. Women sometimes migrate willingly in hopes of better economic opportunities, as their families aren’t investing in them and there is little economic opportunity in Nepal, and are immediately deceived or later sexually abused. Additionally, families sometimes sell their daughters into trafficking or marriages, as they need the money due to the subsistence farming economy, and believe that wherever else their daughters go, there will likely be better economic opportunities.

Over the past few decades, governments and NGOs have granted more attention to the issue of human trafficking, beginning in 1986 with the Traffic in Humans (Control) Act. This act was a good start, but focused on trafficking for the purpose of curbing prostitution, which placed blame on the women being trafficked instead of the traffickers. After the1986 law, trafficking became a priority issue in Nepal, and more NGOs and community-based organizations began to develop socially, economically, and culturally sensitive programs.Significance

Human trafficking is significant to our exploration of Nepal because of the popular argument that human trafficking and child marriages will become even more problematic after the 2015 earthquake. Money is now of the utmost importance for the Nepali population, and trafficking is a, unfortunately, quick source of income. Although few may be maliciously exchanging their daughters for money, most are selling their own children off because they believe it might be in their best interest, or because they can no longer support their children and their education.

“They do love their daughters. It’s not that they hate their daughters. But you know —the temptation of a little money, 3,000 rupees, 4,000 rupees, $50, $60 a year is a big money for their poor family. So, that’s—that’s why they were doing it.”- Som Paneru, “Daughters for Sale” PBS Broadcast [1]

The earthquake itself has created many more urgent problems that will be prioritized above preventing human trafficking, therefore halting the previous progress Nepal has achieved and leaving thousands vulnerable to the trafficking industry. Finally, Nepal’s post-earthquake environment is importantly different in many ways than its pre-earthquake environment. It has not only worsened certain pre-existing vulnerabilities, but also created completely new ones. Therefore, the challenges and interventions that existed before April 2015, however successful they may have been, may be ineffective or in need of modification.

- [6]

- [11]

- [7]

Core Challenges

Human trafficking in Nepal presents challenges that transcend an array of national boundaries and the nation has long affirmed its status as a source from which people are perpetually subjected to forced labor and sex trafficking, despite governmental and NGO-based anti-trafficking efforts. The recent earthquakes will undoubtedly fuel Nepal’s unyielding battle with human trafficking, leaving ample room for unique interventions and proactive responses to this unanticipated calamity. It’s important to recognize that these challenges are intrinsic to Nepal’s long relationship with human trafficking and the recent earthquakes will hopefully redirect attention to the issues.

Structural violence, migration, and invisibility make visible the forces that conspire to constrict Nepali agency. Each anthropologically rooted theme sheds light on a critical lens through which human trafficking can be contextualized, and hopefully best responded to.

!["...It is this disaster that is most responsible." - Mohammed Ishfaq Haider, deputy police commissioner at the Indira Gandhi Airport [27]](https://journeys.dartmouth.edu/NepalQuake-CaseStudies/files/2015/06/Core-Challenges-Image-1-1024x614.jpg)

“…It is this disaster that is most responsible.” – Deputy Police Commissioner at the Indira Gandhi Airport [27]

Structural Violence – Human trafficking in Nepal is perpetuated by the nation’s economic structures and gendered practices that produce a landscape in which the violent treatment of bodies is commonplace. Economic vulnerabilities, of households in pursuit of financial security, are heightened by the structural violence that is pervasive in Nepal. Global actors in advocacy and relief have voiced their concerns towards the surge in exploitation of Nepali children who were orphaned as a result of the recent earthquakes.

Coercing parents to relinquish their children to orphanages is method through which traffickers capitalize on Nepal’s convoluted adoption trade. Parents willingly succumb to these structurally violent transactions with the hope of gaining secure economic futures, increased access to education, and an improved quality of life. This institutionalization of children functions synergistically with the newfound risks of “orphanage voluntourism” in Nepal. As beneficent donors support Nepalese orphanages, their purposive aid-related actions propel a structurally broken system, resulting in unintended consequences that fuel the commodification of child bodies.

[28]

Vulnerability of migration – Nepal faces the multifaceted challenge of responding to both domestic and international trafficking practices and realities. Women that travel from Nepal to India for forced prostitution contribute to one of the most convoluted global routes and because most criminal networks are centered in India, the identification and retribution of these traffickers is exponentially more difficult.

The Nepal-India border presents a unique challenge, which dates back long before Indian independence, when the Open Border policy between the two nations was established [29]. This leaves 1,000 miles of unmanned and untamed geographies of vulnerability where migration of traffickers and their victims is left virtually unaccounted for. Migration presents tremendous obstacles that must be approached through partnerships between Nepal and India, and all parties responsible for transactions and patrol of the border. In the midst of the post-earthquake Nepal, options and resources for the Nepalese are limited. Vulnerabilities in response to socio-economic realities of Nepal in the present day have not hindered people’s willingness to go abroad in pursuit of any and all opportunities.

[30]

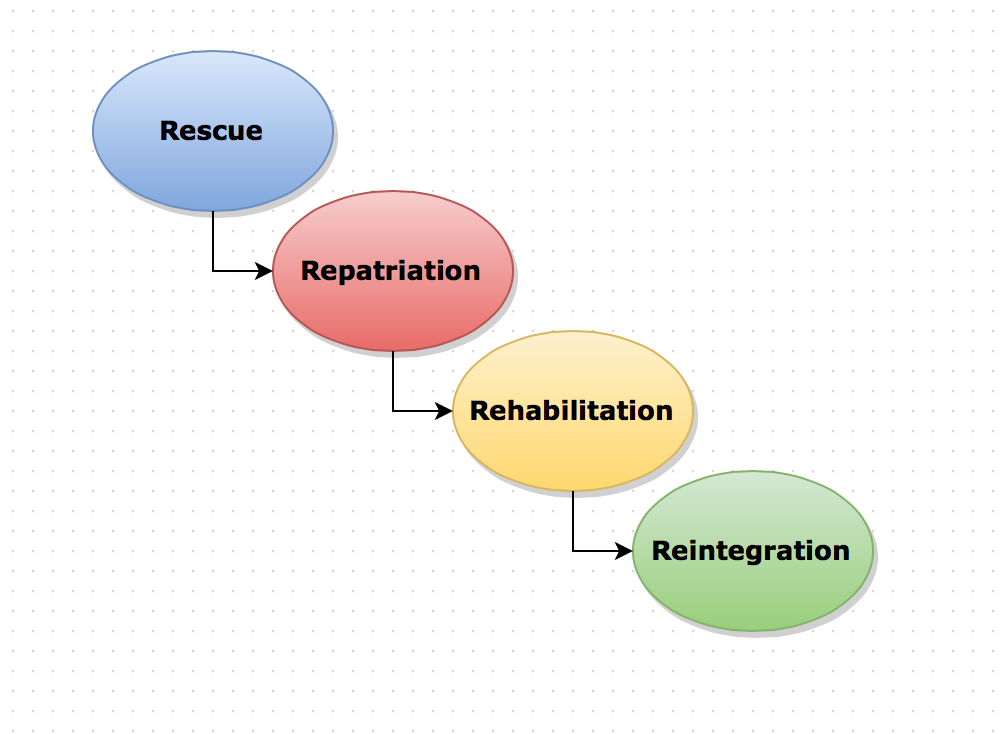

Invisibility of rehabilitation – Challenges after trafficking are as important to consider when contextualizing something as vast as human trafficking into Nepal’s ornate social and cultural history. Rescue, repatriation, rehabilitation, and reintegration are the 4 R’s associated with the complex aftermath of dealing with victims of trafficking and have embedded within them the intricacies of invisibility, secrecy, and stigma most typically associated with sex labor and forms of rape [31].

In Nepali culture, the stigma of rape makes it extremely difficult for a woman who has been raped or violated to return to her village and reintegrate into society. Cultural norms in Nepal value a girl’s virginity at marriage and women who have participated in acts of sex trafficking are seen as “dirty” or “spoilt”, despite having no agency to control their fates. Another layer is added when family rejection of a Nepali victim is considered because their fear of social exclusion from a wider community is produced from the daughter’s “shameful” behavior, further reinforcing the victim blaming dynamic that co-exists with personal episodes of isolation and secrecy around human trafficking in Nepal.

Remaining challenges include:

– The large gaps in quantitative data on human trafficking in Nepal

– The reliance on NGOs and non-profits to provide aid and refuge due to the lack of responsibility assumed by the police and legal system

– Acknowledging and being accountable for men and boys as potential victims of human trafficking

Possible Interventions

In order to create a unique intervention for human trafficking, it is first necessary to establish the type of interventions that already exist so that it would be possible to modify them and make them more efficient. With human trafficking, interventions can take place on three dimensions: prevention, interception, and rehabilitation.

Prevention – Several NGOs have targeted certain ‘at risk groups’ with whom structural violence had made vulnerable to human trafficking. There is very little concrete evidence that identifies the factors that create vulnerability, therefore such groups are deemed ‘at risk’ largely based on common sense [25]. Thus far, such groups consist of lower caste women, school drop outs, the impoverished, and unmarried young girls. For preventative measures, NGOs have adopted the strategy of raising awareness among populations that are deemed at risk by giving radio broadcasts, speeches, and seminars about the danger of human trafficking in order to prevent further acts of trafficking and to make the population more aware of their vulnerability.

Interception – Interception of suspected trafficking activity at the Indo-Nepal border is already carried out by NGOs and police forces. One NGO that does this is, for example, is 3 Angels Nepal. During an interview, 3 Angels’ international ambassador Belinda Bows explained the importance of such surveillance, “Nepal and India have an open border policy. Taking women and children across a border that is 1,000 miles long… is an easy process” [26]. 3 Angels has set up multiple checkpoints along the border to intercept trafficking, and through their efforts, they have been rescuing an average of 12 girls daily from human traffickers [12]. Within three years, they have rescued over 4,000 girls [12].

“Interception is the most effective form of rescue.”- Belinda Bows, International Ambassador for 3 Angels [26]

Rehabilitation – Rehabilitation centers are typically run by NGOs, as the Nepalese government does not offer a reintegration policy. As discussed in our core challenges, cultural norms that value women’s virginity causes a stigma towards trafficked women and makes integrating back into families and communities very difficult.

A Collaborative Approach – First of all, there is the possibility that preventative measures are not reaching all groups that are most susceptible to trafficking. More scholarly analysis on the issue of susceptibility to trafficking could uncover these hidden groups, and it is only then that the preventative measures would be most effective. Secondly, all parties who monitor the border should collaborate with community and urban-based initiatives to see if groups arrive at their destination safely. Furthermore, police could escort women and children traveling across the Indo-Nepal border, thereby eliminating the chances that they would be trafficked after crossing the border. Police officers often do not act in the best interest of trafficking victims. With a responsible and united police force, trafficking intervention would be much more effective. Lastly, when girls are brought back to their families and communities, the NGOs should engage in dialogue with the family in which there is conversation about the experience and causes of trafficking. This dialogue should be done in the presence of the individual who was trafficked so that she also may not feel shame from her experience.

In the aftermath of the earthquake, individuals who have been susceptible to trafficking are now even more vulnerable. The heightened danger of the situation calls for a unique intervention that modifies the pre-existing structures. Any organization that is able to synthesize all of these unique interventions into a system that addresses prevention, interception, and rehabilitation will surely make a profound impact.

Exemplars

Maiti Nepal was founded in 1993 by a group of socially committed professionals that aimed to protect Nepali girls and women from crimes like domestic violence, child prostitution and labor, and various other forms of explicit exploitation. The social organization actively works to find justice for victimized girls and women by engaging in legal battles and criminal investigations against traffickers and their convoluted networks.

Maiti's Border Surveillance Team of Kailali intercepted five girls who were being trafficked to Punjab, India today. pic.twitter.com/3YNw0bn6LE

— @Maiti Nepal (@MaitiNepal) June 8, 2015

[25]

As an organization that transcends local, national, and international boundaries through their advocacy for young vulnerable populations of young Nepali women, Maiti Nepal has established transit homes where local surveillance teams work closely with border police to effectively and efficiently respond to calls for assistance by potential victims. Maiti Nepal’s domestic initiatives focus on rehabilitation and reintegration programs, prevention houses that provide food, shelter, and education, and vital legal assistance for under-resourced and victimized women.

- Thankot, Kathmandu Transit Home [21]

- Maiti Nepal Legal Assistance [22]

3 Angels Nepal (3AN) is one of Asian Aid’s humanitarian agency partners that strives to stop human trafficking in its tracks. 3AN believes in interventions that focus on prevention strategies for vulnerable children at risk for being trafficked or on pathways towards recovery. The organization’s human trafficking rescue program acts through a lens of prevention and deals directly with the vulnerabilities of migration. 3AN Nepal has set up several checkpoints along the border between Nepal and India to intercept traffic and rescue girls before they’ve reached a next destination. To facilitate safe spaces for children involved in any part of the convoluted network of human trafficking in Nepal, 3AN facilitates children’s homes, prison outreach programs, and health education initiatives.

[12]

Discussion Questions

1. In what ways could you imagine Nepal’s pre-earthquake human trafficking interventions translating poorly to the nation’s post earthquake environment? How could an NGO in Nepal better cater its initiatives to serve the most vulnerable populations?

2. Given the outpour of global aid to the earthquakes in Nepal, how can these resources be more effectively leveraged towards human trafficking?

3. An anti-human trafficking advocate would argue that directing resources towards human trafficking in Nepal has multiple benefits. In what ways can human trafficking programs in Nepal “bend” their initiatives towards a more “diagonal approach” that positively impacts other aspects of the nation’s health and development?

4. Envision a Nepal in which subsistence farming was not the dominant activity and the average Nepali did not exist below the poverty line as we know it. How would human trafficking manifest in this environment?

Additional Readings and Resources

Core Readings

1. Sex Trafficking in Nepal: Context and Process: A broad historical and contextual account of human trafficking in Nepal. The data used in this journal is slightly outdated (late 1990s-early 2000s), but this is one of the most holistic and informative pieces of literature on the topic.

2. Female Sex Trafficking in Asia: The Resilience of Patriarchy in a Changing World: This book uses empirical evidence to point to the similarities and differences of human trafficking in Asian nations. Recommendations for prevention strategies and intervention designs are included.

3. Unicef Fears Surge in Child Trafficking After Nepal Quakes: A brief and informative overview of the ways in which the earthquake changes Nepal’s human trafficking situation and renders the children even more vulnerable than before.

Core Visual Resources

1. Combatting Trafficking in Nepal (2013) – USAID

2. Tin Girls (2003) – Miguel Bardem

Additional Readings and Resources

1. Nepal Quake Survivors Face Threat From Human Traffickers Supplying Sex Trade

2. Nepal’s Quake Survivors Face Increased Risk of Trafficking

3. An Assessment of Laws and Policies for the Prevention and Control of Trafficking in Nepal

References

1. Transcript: Daughters for Sale. (2008, December 19). Retrieved August 24, 2015, from http://www.pbs.org/now/shows/414/transcript.html

2. “Adult and Youth Literacy: National, Regional and Global Trends, 1985-2015. UIS Information Paper.” (2012): n. pag. UNESCO. UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2012. Web. 17 Aug. 2015. http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Documents/UIS-literacy-statistics-1990-2015-en.pdf

3. “Nepal: In Earthquakes’ Wake, UNICEF Speeds up Response to Prevent Child Trafficking.” United Nations News Centre. N.p., 22 June 2015. Web. 18 Aug. 2015.http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=51213#.VddNbmAwjzI

4. “Rural Poverty Portal.” Rural Poverty Portal. IFAD, n.d. Web. 24 Aug. 2015. <http://www.ruralpovertyportal.org/country/home/tags/nepal>.

5. Pravettoni, Riccardo. “Trafficking of Women and Girls in Nepal.” Trafficking of Women and Girls in Nepal. Women at the Frontline of Climate Change – Gender Risks and Hopes, 2011. Web. 24 Aug. 2015. <http://www.grida.no/graphicslib/detail/trafficking-of-women-and-girls-in-nepal_a3fc#>.

6. Adhikari, Saroj. “Eartquake Nepal_15.” Flickr. Yahoo!, 26 Apr. 2015. Web. 24 Aug. 2015. <https://www.flickr.com/photos/131831374@N07/17994877028/in/photolist-tq9s1u-sqNgQ6-s6dHKQ-rqNRWS-snP6rP-sqNeKe-rotCb5-sKSeTZ-s29GK4-rotCYC-sibRBG-s3UBHQ-s3UCfw-skjzqS-gJbp8f-v9VgLA-so6n3Y-sqoAeF-s8VUxi-s8MVQo-s74gDT-vSFiWE-vSFkmf-vdgYbh-sqmpSZ-so6aMm-so6siN-so6jVS-sqmuQz-rtzr2P-sqmDLa-sqmjKK-s8W6Q8-rtzzdi-rto9BC-s8MKzo-rtzk3K-sqoeEV-ubNU5Q-v6vmEy-v8PsJZ-uRnrGa-ubYzK2-ubNUHU-ubYAgH-rotD7d-s42yDi-wDGcu1-rotC53-skjyob>.

7. Goldmann, Reinhard. “108 Prayers for Kathmandu – Day 33.” Flickr. Yahoo!, 19 July 2013. Web. 24 Aug. 2015. <https://www.flickr.com/photos/goldi_lichtbilder/18598209201/in/photolist-sczzEV-84qw28-t5iCvm-t5iuEm-uksFDk-w94WNb-sPrapg-tFgwnJ-s9q8dR-v2ncaN-tMhr3g-wUVio5-wEKmbB-wUUnfA-wEBH2m-w1cUVb-wEC3Sw-wEJdoK-wEAZEy-wWtxy5-w1kKkc-tMhx4K-tM92Nf-s6nGN2-tMhuUK-wWuozw-w1cTyd-wEBNTm-w1mCQM-wUUU49-wUUxTQ-wUUvfJ-w1mRjK-wUUhhj-wWtFKf-wEK8Ca-wUUPNf-wEBdDY-wXeBUK-wEC8m1-wWuJr5-wXeyFF-wEC1jN-wEBFt9-w1mMc6-wXdDhX-w1n5Fp-w1draE-wXLjTV-wEHWgV>.

8. Batha, Emma. “Child Marriages, Trafficking Will Soar after Nepal Quake: Charity.” Reuters. Thomson Reuters, 19 May 2015. Web. 24 Aug. 2015. <http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/05/19/us-quake-nepal-childmarriage-idUSKBN0O426M20150519>.

9. Gladstone, Rick. “Unicef Fears Surge in Child Trafficking After Nepal Quakes.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 19 June 2015. Web. 24 Aug. 2015. <http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/20/world/unicef-fears-surge-in-child-trafficking-after-nepal-quakes.html?_r=0>.

10. Ruffins, Ebonne, Gena Somra, and Farhad Shadravan. “Rescuing Girls from Sex Slavery.” CNN. Cable News Network, 30 Apr. 2010. Web. 24 Aug. 2015. <http://www.cnn.com/2010/LIVING/04/29/cnnheroes.koirala.nepal/>.

11. Hennink, Monique, and Padam Simkhada. “Sex Trafficking in Nepal: Context and Process.” Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 13.3 (2004): 305-38. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal. Sept. 2004. Web. 24 Aug. 2015. <http://amj.sagepub.com/content/13/3/305.full.pdf html>.

12. http://www.3angelsnepal.com/Human-Trafficking

13. Orlinsky, Katie. “Women, Bought and Sold in Nepal.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 31 Aug. 2013. Web. 24 Aug. 2015. <http://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/01/opinion/sunday/women-bought-and-sold-in-nepal.html?smid=fb-share&_r=0>.

14. Punaks, Martin, and Katie Feit. “The Paradox of Orphanage Volunteering.” Trafficking in Nepal – Womenfreedomforum.com. Next Generation Nepal, 2014. Web. 24 Aug. 2015. <http://womenfreedomforum.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=456&Itemid=80>.

15. Mathema, Padma. “Trafficking in Persons Especially on Women and Children in Nepal.” The American Journal of International Law 95.2 (2001): 407. UNODC. National Human Rights Commission. Web. <https://www.unodc.org/pdf/india/Nat_Rep2006-07.pdf>.

16.Goldberg, Eleanor. “Hundreds Of Children In Nepal Are At Risk For Trafficking After Earthquake. Here’s Who’s Helping.” The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 22 June 2015. Web. 24 Aug. 2015. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/06/22/nepal-children-trafficking_n_7637776.html>.

17. Renda, Lauren. “Across the Border: Nepal’s Struggle with Human Trafficking.” The Womens International Perspective. N.p., 25 May 2012. Web. 24 Aug. 2015. <http://thewip.net/2012/05/25/across-the-border-nepals-struggle-with-human-trafficking/>.

18. http://www.worecnepal.org/#

19. Naik, Vipul. “Nepal and India: An Open Borders Case Study.” Open Borders. N.p., 21 Mar. 2014. Web. 24 Aug. 2015. <http://www.worecnepal.org/#>.

20. “Combating Trafficking in Nepal.” YouTube. USAID Nepal, 5 June 2013. Web. 24 Aug. 2015. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NnPg9Wiqy6M>.

21. Transit Home – Thankot. Digital image. Maiti Nepal. Softgriha Solutions, 2013. Web. 15 Aug. 2015.<http://www.maitinepal.org/index.php?content=contentpage&id=45&pagename=Thankot,_Kathmandu>.

22. Legal Assistance of Maiti Nepal. Digital image. Maiti Nepal. Softgriha Solutions, 2013. Web. 10 Aug. 2015. <http://www.maitinepal.org/index.php?content=contentpage&id=38&pagename=Legal_Assistance_of_Maiti_Nepal>.

23. Angara, Pon. “Poverty. Homelessness. Orphaned Children. Lost Livelihood. A Perfect Storm for Human Trafficking. Http://t.co/yohaCTWzt4.” Twitter. N.p., 8 Aug. 2015. Web. 25 Aug. 2015. <https://twitter.com/barkadacircle/status/630019630267023360>.

24. Moench, Mallory. “In the Wake of the #Nepal Tragedy, the Poor Are Even More Vulnerable to #trafficking. How Can We Protect Our Sisters? Http://t.co/YreGfOQWuR.” Twitter. N.p., 17 Aug. 2015. Web. 25 Aug. 2015. <https://twitter.com/mallorymoench/status/633182155263356928>.

25. Evans, Catrin. Bhattarai, Pankaja. A Comparative Analysis of Anti-trafficking Intervention Approaches in Nepal. 2010. Web. 15 Aug. 2015. <http://asiafoundation.org/resources/pdfs/nepaltraffickingmodels.pdf>

26. Bilala, Anne-Yolande. Interview: Belinda Bow, International Ambassador for 3 Angels. 12 March 2014. Web. 15 Aug. 2015 <http://www.diplomaticourier.com/interview>

27. Chitrakar, Navesh. Armed Nepalese police help people in Sindhupalchok district board a helicopter to Kathmandu after last month’s earthquake. Digital image. Nepal Quake Survivors Face Threat from Human Traffickers Supplying Sex Trade. The Guardian, May 2015. Web. 25 Aug. 2015. <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/may/05/nepal-quake-survivors-face-threat-from-human-traffickers-supplying-sex-trade>.

28. Nepal’s Bogus Orphan Trade Fuelled by Rise in ‘voluntourism’ Guardian News and Media Limited, 2015. Web. 25 Aug. 2015. <http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/may/27/nepal-bogus-orphan-trade-voluntourism>.

29. Naik, Vipul. “Nepal and India: An Open Borders Case Study.” Open Borders The Case. WordPress, 21 Mar. 2014. Web. 26 Aug. 2015. <http://openborders.info/blog/nepal-and-india-an-open-borders-case-study/>.

30. “Home: A Society Free From Trafficking Of Children & Women”. N.p., n.d. Web. 26 Aug. 2015. <http://www.maitinepal.org/>.

31. “International Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children.” The American Journal of International Law 95.2 (2001): 407. National Human Rights Commission, 2008. Web. 2015. <https://www.unodc.org/pdf/india/Nat_Rep2006-07.pdf>.