Individual Invisible

Written by Tailour Garbutt

It started with nine documents. Nine documents in a thin manila file. I hadn’t known what I was looking for when I came to Rauner that day. I was searching for a story. Not Edward Mitchell’s story, but a story. I didn’t know where to start. I had an assignment: Find a document; illuminate something about a person connected to the document. I should have been more prepared. Some names in hand, ready to list them off when the librarian asked. But I wasn’t. That unpreparedness led me to Mitchell.

I approached the research desk, syllabus and laptop in hand. I read off the assignment. The librarian nodded. “Where did you want to start? Did you have a specific subject matter in mind?” The questions seemed simple enough, but the answers evaded me.

I responded with the first thing to come to mind. “Maybe the first Black woman to attend Dartmouth?”

“It’s unclear who actually has that title. Many women claim it, so that may be a difficult starting point.”

“How about multi or biracial students?”

“Well, the first Black man who attended Dartmouth in the 1800s was mixed race. His name was Edward Mitchell. Students wrote a petition on his behalf so that he would be admitted to the College. That petition could be your document. I actually have it out already, set aside for an event tonight. I can also get Mitchell’s alum file.’”

I began to fill out the forms so that I could handle the materials. The librarian shared a brief exchange with another staff member as he stood.

“I thought that file went missing?”

His voice was low, but clear. “I think it was rebuilt.”

I was expecting a hearty file, crammed with scraps of paper, old newspaper clippings, previous assignments. Dartmouth constructs alumni files for all students, honorary degree holders, and “adopted” members of the class. Files are compiled by the Alumni Records Office and made available in Rauner postmortem. I have a file. I have no idea how thick it is or what’s in it, but I know it exists.

Mitchell’s file was light, too light. I opened it to find the first page almost completely blank. His name was in the top left hand corner, the word “MISSING” just below it. “Search conducted, and file now classed as missing. Dec. 20, 2013. Some materials known to have been in his file are replacement photocopies.” Nine photocopies. The majority of them were excerpts from books. Histories of the College, Alumni Magazines. Mitchell’s name was mentioned briefly, a few sentences. There was a ledger of his student account. A letter mentioning invitations to a class reunion. It was too little. Too little to encompass four years at Dartmouth College, let alone his post-graduate years.

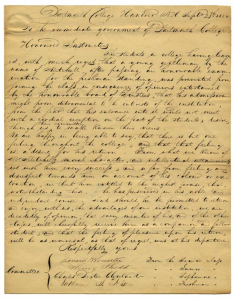

The petition, the document the librarian suggested I focus on, was separate from Mitchell’s file. A photocopy was included in the file, but the actual document had a folder of its own. It was the only document of the nine dedicated entirely to Mitchell. More than a sentence, more than a paragraph, it was a single sheet of paper. The page was small. The size of the document didn’t seem proportionate to its purpose. A fine layer of plastic encased it, attempting to protect it from time. The document was tinged a golden yellow color. A stylized script consumed the page. 190 years had passed since this petition was written. September 25, 1824. Addressed “to the immediate government of Dartmouth College,” specifically, the “Honoured Instructors.”

Four names were signed at the bottom of page. Four names that were not Edward Mitchell. Mitchell didn’t write the petition; it was written on his behalf. He was the center, the reason for writing. Leonard Worcester, Henry Shedd, Charles Dexter Cleveland, and Nathaniel S. Folsom were the names behind the script. Their names represented more than their own voices; they were the student body of Dartmouth College in 1824.

I was unsatisfied with the descriptions of Mitchell in his file and the few sources I was able to find online. He didn’t have a Wikipedia page devoted to him, but with the information I found, I could surely start one.

- Edward Mitchell: First African American man to attend Dartmouth College.

- Born on January 27, 1794 in Martinique, West Indies.

- Seemingly brought to the South as a result of the slave trade, little is known of transition from the West Indies to the US.

- Francis Brown, Dartmouth’s third president, brought Mitchell to the Northeast.

- October 1819, Brown traveled to Richmond, Virginia and Salisbury, North Carolina to regain some semblance of health. Symptoms of pulmonary disease.

- Brown unable to return to Hanover accompanied by only his wife, enlisted the assistance of Mitchell.

- Mitchell travelled North with the Browns, “remained an inmate of the family after Dr. Brown’s death” in 1820.

- Mitchell “remained in his family after the death of the president on equal terms with his children.”

- 1824- Mitchell applied to Dartmouth College.

I was back at the petition. The Board of Trustees denied Mitchell admission on the grounds that “his presence would be unacceptable to the students.” Charles Dexter Cleveland, a rising sophomore at the time, spearheaded the movement responsible for the petition. A “dark skinned Caucasian,” Cleveland believed that if skin color determined one’s right to admission, he would not be a student at the College either.

“From what we know of Mr. Mitchell’s moral character and intellectual attainment we wish him every success; so, far from feeling any disrespect towards him on account of his colour or extraction, we think him entitled to the highest praise, that notwithstanding these, he has persevered in his noble and independent course.” After the release of the petition, the Board of Trustees overturned their decision, admitting Mitchell to the freshman Class of 1824. While at Dartmouth, Mitchell studied Divinity Studies. He graduated in 1828 and was ordained in the Hanover Baptist Church in 1829.

I studied the documents closer, hoping I overlooked something. I wanted to find that piece of information that would lead to more.

I approached the research desk again. A different librarian sat alone, straightening some papers. I wanted her to direct me toward the missing link. This was not all there was to Edward Mitchell’s story. Accounts were missing. There were gaping holes in his life before, after, and during his time at Dartmouth. Invisible, unknown, erased. I asked for any other files that referenced him.

She paused. Nodded towards the table. “That’s it, dear. We only have more in-depth information and files on prominent individuals.”

Prominent. Prominence. Importance. Important.

June 2014

I sat among forty-five other Dartmouth students, clustered in groups of three or four. The tables were arranged along the perimeter of a large, oval-shaped room. Friday morning, the first week of the term. That day, we were all acutely aware of the downfalls of the 9L hour. The professor asked a question and a few hands went up across the room.

His voice was clear and certain as he called, “Yes, Tailour.” My hand wasn’t raised. My eyes moved quickly from my computer screen to his face. But he wasn’t looking at me. Confused, I followed his gaze. It was directed towards another girl on the side of the room opposite from me. He seemed flustered as he recognized his mistake. I tried to make sense of the mix up, his sudden change in demeanor. The student he had called on was my friend, but there was no way for him to know that. Our outfits, hair, body types, facial structures…they were all so different. Yet, in the midst of the class, our complexions set us apart.

The professor tried to recover quickly, redirecting the conversation to the research we had been discussing. Class ended. As I was gathering my things, I remembered the question I had planned to ask earlier that morning about an upcoming assignment. I moved towards the front of the room. The same friend the professor had mistaken for me followed a few feet behind, waiting to ask her own question.

He was addressing us before we had reached the front desks. He spoke quickly, his words blending together.

“I’m sorry, I’m sorry. I can’t believe I did that.” He briefly paused, waiting for us to accept his apology. “You know what I did there, right?” He raised his arms until his hands were in line with his chest, palms facing upward towards the ceiling. When neither of us tried to respond, he continued.

“Women of color?” He shrugged his shoulders, an uncomfortable laugh filling the silence. He made a sweeping gesture with his arms, motioning between the two of us. It was as if he was trying to show us a connection that neither of our eyes would ever be able to detect.

“I’m sorry, so sorry.” The forced laughter continued to fill the lapses of silence between his sentences. “Forgive me? I get a pass just this once, right?” His questions seemed rhetorical, as if he already knew what our answers would be.

It was my turn to speak. The words I wanted to say were replaced with the words I was expected to say. I spoke quickly, eager to get to my question about the assignment, change the subject.

It lingered in my mind. My name, the easier of the two to pronounce, was suddenly not my own. I was no longer an individual. A body, no name. I was reduced to my complexion. Identified by the color of my skin instead of the letters of my name. T. A. I. L. O. U. R. He had replaced my name with “woman of color.”

At first, I counted it as coincidence. But the short descriptions in Mitchell’s file fell into a pattern all too easily.

“A young colored boy, named Mitchell.”

“Edward Mitchell, a coloured Creole.”

“Edward Mitchell, a negro.”

“Edward Mitchell, a young man to whom naught could be objected except that he was somewhat tinged with African dye.”

Dartmouth College was one of the first American colleges and the first Ivy League to admit an African American. Harvard followed over forty-five years later in 1870. A History of Dartmouth College states, “The precedent thus established has from that time governed the College, which has shown an unfailing hospitality to the negro, even when the doors of other institutions were closed against him.” The negro, him. One body forced to represent a collective. One individual reduced to race.

I searched for a picture, wanting to see the physical features that were unique to Mitchell. There was no picture to study, no image to link to his name.

I kept coming back to the first sheet of paper. The short statement on the page, seemingly definite. Shrouded in false certainty. Missing File: Classed as Missing December 20, 2013. No explanation. No hypothesis. Librarians had rebuilt the file, but there was no indication of what pieces of the narrative had gone missing with the original. How had the file disappeared? Had the pieces of Mitchell’s story that I wanted to exist ever been there at all?

I tried to imagine what Mitchell’s lived experience was like in Hanover during the 1820s. There wasn’t much documentation. No photographic accounts. It was as if people didn’t feel the need to document the present because they were just too busy living in it.

Mitchell’s name was listed in the College’s Course Catalog (1820-1845). The first few pages had the names of all students and various statistics. Mitchell was 1 of 44 freshmen. e was 1 of 228 Dartmouth undergraduate and medical school students. There was 1 College president, 7 professors, 2 tutors, and 1 preceptor of Moore’s School. They were Dartmouth College in October of 1824.

I studied the requirements for admission, amazed at how drastically Mitchell’s Dartmouth contrasted with the Dartmouth I knew. To qualify, he had to “be well versed in the grammar of the English, Latin and Greek Languages, in Virgil, Cicero’s Select Orations, Sallust, the Greek Testament, Dalzel’s Collectanea Græca Minora, Latin and Greek Prosody, Arithmetick, and Ancient and Modern Geography; and that he be able accurately to translate English into Latin.”

I thumbed through two long drawers of card catalogs, hoping to find manuscripts of letters or notes that described the College and student life during Mitchell’s time. Hundreds of cards were divided by year, each with a short description of the document it represented. I couldn’t find Mitchell’s voice in the manuscripts, but I searched for others.

I found the voice of David Peabody in a letter home, writing about his journey to Hanover and his experiences at the College. He wrote to his “ever dear parents” on September 13, 1824.

I am pleased here in every respect…All the College officers I have seen, appear like fine, pleasant, and learned men, wishing to import in equal portions, knowledge and happiness to all.

I found Jacob Batchelder’s voice in a letter he wrote to his sister, Lydia, on July 27, 1827.

But it is really a pleasant life, perhaps as near as happy one as one could live.

I long to get home and see you all, and see how the farm looks…

With each voice I uncovered, I wanted Mitchell’s more. Where did he fit into all of this? I wanted to know how his experience was similar to mine, how they were connected. What would future generations find of my Dartmouth experience? What would be missing from my file, my story?

Questions still lingered. The story and its missing pieces stayed with me.

“How are classes going?” The inquiry came from my research advisor, Professor Reena Goldthree.

My mind went to Mitchell. I began to rattle off the details I knew, the mysteries I wanted to understand. She listened intently, letting me inundate her with information. She was one of the few people I had encountered who already knew Mitchell’s name.

“You should talk to Woody Lee.” I had heard his name in passing, but I wasn’t sure in what context. “He’s a Dartmouth alum who has been researching the history of Blacks at Dartmouth in partnership with other alums. He was on campus last spring to hold some discussions about his work. I’m sure he’d love to talk to you about it.”

She searched through her messages to find Lee’s email so that I could contact him. The web of connections continued to grow. I had a lead.

I found it. Actually, it found me. The piece of information, the person that would lead to more. Woody Lee. I just had to write an email. Ask questions, get answers. It seemed simple, but suddenly as I was trying to condense my thoughts into text, I felt that I had too much to say; too much I wanted to know. I wrote two paragraphs and pressed send. A few hours later, I had a response.

Hi Tailour,

Thanks for your email. I do have quite a bit of information on Edward Mitchell. Attached is a talk I gave at Hood earlier this year which summarizes some of what I’ve discovered and come to know. There’s much more, but it will give you an idea of what ground I have covered. As you will see, there is a large collection of Mitchell Family papers in Montreal which includes writing in his own hand ca. 1828.

It was short. Five sentences. Five sentences that gave me hope. Mitchell was part of the past, but he felt so present. There was too much left to learn about him for him to be considered a part of the past. Lee’s phone number was included at the end of the email, just before his signature. I clicked on the attachment. I scrolled through the pages. When I came to the last sentences, I reread them a few times: “It is a history arguably unique and distinguished among American colleges and universities. But it is a story yet to be fully uncovered, understood, and woven into the Dartmouth family narrative.” The transcript of Lee’s discussion at the Hood outlined Mitchell’s life and legacy. It brought me a few steps closer to Mitchell, and a few steps closer to Lee.

Dr. Forrester “Woody” Lee is a Dartmouth ’68. Lee’s Dartmouth wasn’t Mitchell’s, nor was it mine. His four years at the College took place in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement. For 150 years after Mitchell’s graduation, only 133 Black male students graduated from Dartmouth. Woody Lee was one of them.

Lee and his classmates built a community within the larger Dartmouth community. They organized themselves and established a presence on campus by creating Dartmouth’s Afro-American Society (AAm). Lee was the first president of the AAm. During their undergraduate careers, the legacy of those who had come before them remained unknown, unsaid.

“If we knew the long history of Black students at Dartmouth, we would have felt more legitimacy in our claims.”[1]

In August of 2014, Lee went to the McCord Museum of Montreal, Canada with Dennis Young, a Dartmouth ’69. Their goal: Uncover more information about Edward Mitchell. The Museum had acquired a collection of Mitchell’s personal and family papers around 1920. Mitchell’s sermons, student essays, documents written in his own script. From Dartmouth, the trip to McCord was about a three-hour drive. Three-hours separated Dartmouth from a piece of its history.

I called Lee before my first class, pacing back and forth as I listened to the dial tone. When he answered, I sat down at my desk, pen and paper ready. The conversation began quickly. Lee narrated facts about Mitchell as if he was talking about a family member, a brother. If he was pausing to look at notes, I couldn’t tell. His words came in a steady stream.

We started with the first written account of Mitchell, with Elizabeth Gilman Brown’s diary. She had briefly mentioned Mitchell, maybe a few sentences. Lee continued the story, bringing me back to Martinique and Mitchell’s beginnings. He traced the timeline of Mitchell’s life through and beyond Dartmouth. I explained my goal, what I wanted to accomplish through this story. Lee had read my first draft before our conversation.

“It’s as if Mitchell came to Dartmouth, spent four years, graduated. I just don’t understand how there isn’t more information about him and his experiences.”

Lee’s response resonated with me, highlighting something I had been missing. “There was no narrative about being Black in society during that time period. No one thought to record it.” Mitchell attended Dartmouth during the height of slavery. Erasure went beyond Dartmouth. Dartmouth may have participated in it, but the action traversed the country. The idea that Blacks could make progress wasn’t even a thought.

I had been focused on the story of a Black man attending an Ivy League, alone. One among hundreds. Mitchell’s story was also something else. “The story of one man making his way.” Mitchell was learning to learn, beginning his life as an academic.

At Dartmouth in 1824, Mitchell wasn’t the face of diversity. Diversity wasn’t necessary or desired as a trait in a college during the 1820s. Had photography existed, his picture would never have been used on the front of a pamphlet to signify difference. He would never be quoted or asked to speak on a panel about diversity at the College. He was an anomaly. He set the precedent, probably without having any knowledge of doing so.

The phone call lasted over an hour. After our conversation, I continued to research, piecing together the information Lee had given me with the other sources I had found in Rauner and online. While searching, I came across Lee’s words again: “When you come to Dartmouth, you feel you’re part of a family. But then you leave the institution and rejoin your own family, and you kind of lose your Dartmouth identity. But then to have someone say you were not the first here—which is what I felt—you’re one of a long line of students who came in small numbers, made their mark at Dartmouth, and made it very successfully. To feel that connected to your institution and to people who look like you and who have dreams and aspirations like you do, I think was magical, certainly for me.”[2] Mitchell’s story had become a part of Lee’s. It was becoming a part of mine.

I began to explore the files Lee was able to send. The majority of the papers remained in Canada, too far for me to access without transportation in such a short period of time. But with what Lee forwarded, I finally heard Mitchell’s voice.

In a class assignment, writing on the subject “Know Thyself:”

Knowledge is said to be power. That is, that in proportion to the degree of knowledge, which a man possesses, he will expect influence on his contemporaries and success, and he will secure for himself a greater degree of present and future happiness, than he otherwise would, if his mind were enshrouded with the veil of ignorance.

In an Outline of the Religious Experience, I heard what his faith meant to him:

I do not recollect any sudden transition from darkness and distress to light and comfort. But I felt a calmness in believing in Jesus Christ, and a delight in him to which I had before been a stranger.

I understood the power prayer held in his life.

I felt a love to prayer and to saints, they appeared to me the excellents of the earth, and when I saw them together commemorating the dying love of the Savior, I often felt strong desire to be among them.

Through the other documents, I came to realize what he meant to the people who knew him. I remembered Lee’s description during our phone call. “Mitchell was the center of the universe at Georgeville, Quebec.” Lee was right. “He was regarded as the most profound theologian ever settled in the section in which he passed so many years of his useful life.”[3]

Questions still linger, for Lee. For me. Edward Mitchell was the beginning. The beginning of the legacy of Blacks at Dartmouth. But how many stories mirror Mitchell’s? How many files are incomplete, “missing?” The whereabouts of Mitchell’s original alumni file remain a mystery. Lee was unaware that the file had gone missing. We may never know why or how the file disappeared, but we also may not need to.

The McCord Museum of Montreal, Canada will not sell the collection of Mitchell papers to Dartmouth. They mean too much. An important part of Canadian history. However, in celebration of upcoming anniversaries, McCord hopes to collaborate with Dartmouth to transpose the documents to the Internet, creating an online archive to make the documents accessible to whoever wants to see them.

Edward Mitchell was the fourth African American to graduate from college in the United States. He was the first African American to graduate from Dartmouth College. He was a scholar, a believer, a lover, a husband, a father, a friend, an individual.

Prominent. Important.

“A man of steadfast integrity; a preacher of marked ability; a scholar that retained the love of learning – the very last years of his life you would find him reading the Bible in the original languages; a true friend; a kind and affectionate husband and father has been called from the scenes of earth. He has fought the good fight and has gone to receive his crown.”[4]

[1] Lee, 2014.

[2] Smith, Steven. “Alumni, Students Inspired by Dartmouth’s African-American History.” Dartmouth Alumni. 10 April 2014. Web.

[3] The Baptist Encyclopedia

[4] Obituary .Stanstead Journal, March 1872.