“If we fail to focus on our mental well-being, then our physical health and subsequently our quality of life gets affected – Our daily living gets affected by it”

Dristy Gurung, Counselor, Transcultural Psychosocial Organization

Abstract

When reflecting upon the damage of the earthquake in Nepal, the physical destruction such as collapsed buildings and crush injuries is obvious. The mental scars that arise from traumatic events are often invisible, however, from the standpoint of international aid and within the Nepali community itself.

Prior to the earthquake, Nepal utilized a vast traditional healing network and a weak, disconnected biomedical system to address mental health issues. The urgency of the current mental health situation in Nepal post-earthquake has created the necessity not only to provide immediate relief but also to restructure the mental health system into a stronger model. If done successfully, the world can view Nepal as a model for post-disaster mental health care as well as a framework for building a system that incorporates a biomedical infrastructure with well-developed local forms of healing.

Background and Historical Context

Nepali Concept of Self

Nepali people view the self in five interconnected parts. To learn about this concept of the self, scroll through the slideshow above. Credit for concept behind artwork of first slide: Ian Harper

Healers attempt to reframe mental illness through different parts of the self according to their specialty. As a result, mental health issues are usually handled by visiting various kinds of healers, often simultaneously.

- Traditional healers such as dhami-jhankris (Nepali shamans) discuss fear, low mood, fatigue, and nightmares with patients to primarily heal the jiu (physical body), man (the heart-mind), and saato (spirit).

- General physicians treat the jiu (physical body) by alleviating pain through biomedicine, especially injections. Patients generally do not discuss issues of the saato (spirit), man (heart-mind), or dimaag (brain-mind) with general physicians. Due to the stigma of dimaag (brain-mind) problems in Nepali culture, general physicians usually refer patients to psychiatrists only if the patient does not improve after several treatments or exhibits psychotic behavior. When a referral does occur, patients often register under false names or seek psychiatric treatment in a different country.

- Psychiatrists themselves are stigmatized because they treat the dimaag (brain-mind), so they often shift focus to the jiu (physical body) by referring to themselves as neuro-psychiatrists and focusing on pharmacotherapy.

- Psychosocial healers follow manosamajik karyakram (psychosocial programs), which reframe mental illness in terms of man (heart-mind) and samaj (society). Before the earthquake in Nepal, this approach was gaining ground with NGOs addressing the aftermath of the 11-year war between the Communist Party of Nepal-Maoists and the Government of Nepal. The NGOs would train community psychosocial workers in one to two week long courses and community psychosocial counselors in four to six month long courses. Psychosocial counselors believe that patients have a man (heart-mind) problem because of their lifestyle and society, which eliminates the stigma of discussing dimaag (brain-mind) problems. Psychosocial programs are not often sought out yet, so they seek patients through community awareness programs and by screening children in schools.

Healers are not evenly divided between specialty or location so access to care is limited, especially in rural areas. Additionally, care is so fragmented between parts of the self that the full health of a patient is never addressed. The most widely utilized health care professionals are the traditional healers, with the limited biomedical resources sought only as a last resort. Although government health services were free of charge, Nepal spent less than 3% of the government budget on health care. There was no mental health action plan or government division dedicated to mental health and there was only one hospital in the country that exclusively addressed mental health, the Mental Hospital in Kathmandu. Outside of Kathmandu, there were only four government hospitals and 25 non-government medical colleges providing psychiatric services.

References: (IASC Desk Review) (Kohrt and Harper)

Significance

Why should we care about mental health in post-quake Nepal? Why is it important for the overall well-being of Nepalis?

On some levels, the question of why we should care about addressing psychiatric trauma in post-quake Nepal is no different from why we should care about treating crush injuries or protecting water sources to prevent cholera: mental illness is a form of suffering that is as legitimate as bodily suffering and the two forms of suffering are highly connected. For Nepali people, the significance of mental health is intuitive, given their understanding of the role of the man (heart-mind), which connects emotions to the jiu (physical body) as well as the iijat (social self) (Inter-Agency Standing Committee).

The burden of mental health problems in post-quake Nepal cannot be summed up cleanly into one photo, graph, or narrative. Instead, the impact of psychological distress manifests itself in diverse experiences, both immediately following the quake and for generations to come.

Click on the interactive timeline below to see some perspectives on how the earthquake has impacted mental health and how mental illness might ripple out to affect other aspects of Nepali life.

Why is mental health in post-quake Nepal important for global health more generally? Nepal can be seen as a microcosm of the global gap between mental health needs and biomedical mental health care treatment. As Dr. Anne Becker describes in the video below, even though mental health has been identified as a pressing global health concern, there are limited resources allotted to mental health (Tomlinson).

Why is mental health in post-quake Nepal important for global health more generally? Nepal can be seen as a microcosm of the global gap between mental health needs and biomedical mental health care treatment. As Dr. Anne Becker describes in the video below, even though mental health has been identified as a pressing global health concern, there are limited resources allotted to mental health (Tomlinson).

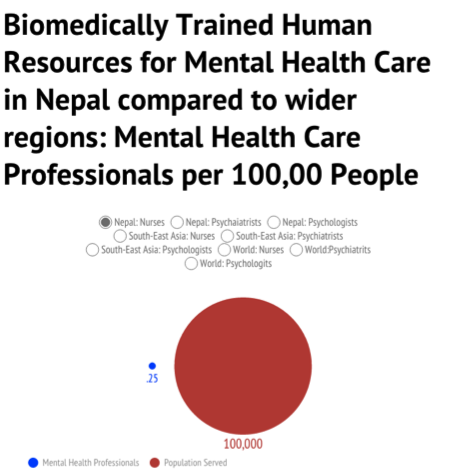

To see how Nepal fits into the global trends surrounding mental health with regards to biomedical resources, click on the chart below:

It is important to note that while other situations may be similar to Nepal in terms of biomedical resources, they are all unique in terms of the non-biomedical mental health care system.

More natural disasters will inevitably occur, particularly in Asia, one of the most disaster-prone areas in the world (Kokai). Programs that prove effective in Nepal can serve as adaptable models for responding to disasters in other communities with fragmented mental health resources. These programs can also provide a framework for incorporating biomedical resources into traditional healing networks in non-crisis settings.

Attending to mental health problems in post-earthquake Nepal is relevant to the larger field of global health because one of the aims of global health is to recognize and mitigate structural inequalities. Treating mental illness falls under this mission because, as Arthur Klienman summarizes, “the experience of insecurity and hopelessness, rapid social change, and the risks of violence and physical ill-health may explain the greater vulnerability of the poor to common mental disorders” (Klienman). In post-earthquake Nepal, we see a culturally specific network of factors that place certain individuals at an increased risk for mental illness.

Click on the interactive diagram to learn more.

Core Challenges

When the earthquake struck Nepal, it damaged an already fragmented mental health care system. The limited biomedical resources worked in parallel with traditional healing, leaving patients without options or continuous care. We identify the key challenges in responding to post-earthquake mental distress to be the invisibility of mental health issues in Nepal due to cultural stigma, the discontinuity between traditional healing and biomedicine, and the low economic prioritization of mental health from the standpoint of both government spending and international aid.

A woman waiting in line at a temporary health clinic Photo Credit: WHO

Nepali Internal Invisibility

- Limited support for patients in their communities due to the cultural stigma against Dimaag (Brain-Mind) problems

- The social suffering associated with mental health issues is so great that some families choose to abandon or hide their affected relatives (Dristy Gurung)

- The stigma surrounding Dimaag (Brain-Mind) problems can create a social barrier that deters people from seeking help

- Mental health problems can be seen as “politically invisible” due to limited government resources allocated to them

- Small amounts (<3%) of government money allocated to mental health issues (WHO))

- Limited access to necessary medication to help alleviate the symptoms of psychiatric disorders

- Nepal’s healthcare workers are overworked and overburdened, struggling to balance providing high quality care with treating the necessary number of patients (Luitel).

Fragmentation

- Biomedical resources are not integrated with traditional healing, with patients only seeking biomedical care as a last resort and biomedical providers not utilizing traditional healing

- Mental health patients do not follow a continuous health care regimen since most of them are treated in outpatient facilities, which reduces the likelihood of recovery

- Large socioeconomic treatment gap with lower income individuals lacking resources for treatment

- Dozens of NGO’s actively working on mental health in Nepal (cidi.org), which can lead to parallel systems being created

International Aid Invisibility

- The problem of mental health is not appealing to many donors because the “success rate is indefinite and a chronological time line for dealing with these issues is difficult to create” (Devkota). Without a concrete plan, it is difficult to convince donors to provide the necessary funds for the additional resources.

- The consistent questioning of mental health interventions from a biomedical perspective is evidence of the way the Cartesian dualism inherent in Western medicine lacks the holistic view of health that the Nepalis embrace.

Source:World Health Organization Desk Review for Nepal unless stated otherwise.

Possible Interventions

Immediate:

Amchi Medicine Clinics

The most efficient and effective forms of “intervention” in times of crisis often come from within the affected community itself. In Nepal’s case, Amchi (Tibetan medical) healers are positioned to respond nimbly, given not only their intimate knowledge of Tibetan medicines but also their holistic understanding of the needs of patients. Since the earthquake, they have promoted resilience through providing food and offering ritual support to both honor the dead and protect the living. For example, Amchi healers address the trauma of loss by traveling to Katmandu and lighting butter lamps for a deceased family member if the family is unable to do so themselves. This is extremely relevant to post-earthquake mental health because their work reduces and dispels spiritual pollution created by the destruction of life during the earthquake (Craig).

An amchi healer lights butter candles Photo credit: Himalayan Amchi Association

Radio Shows

One intervention that has been utilzed by the Nepali group Bhandai Sundai is a radio show into which people can call in to discuss their experiences post-earthquake. This show is an innovative solution to several challenges in providing psychological support post-quake. Not only does it eliminate the problem of physical inaccessibility of some people due to earthquake damage, but also it avoids the issue of the stigma surrounding dimaag (Brain-Mind) distress because it allows people to maintain a level of anonymity. The show also fosters a sense of community support and stigma reduction by reminding Nepali people that they are not alone in dealing with these issues.

To learn more click on the video below:

Temporary clinics

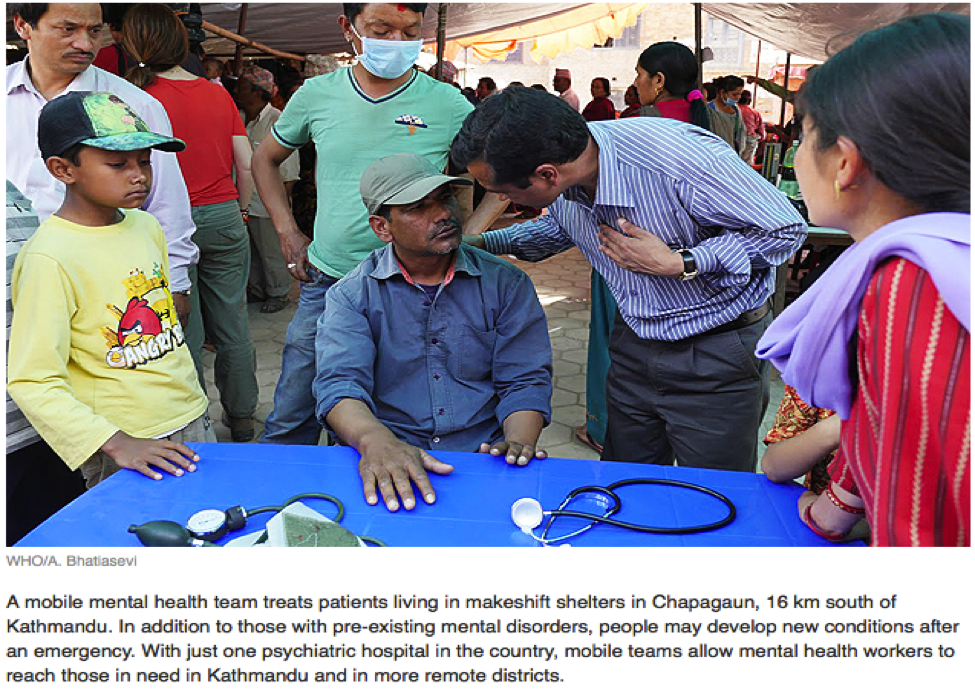

Temporary clinics are a form of intervention that were first deployed outside Kathmandu and have since spread to more remote regions. These clinics see up to 500 patients a day and, while their staff is obviously pressed for time, they have been able to identify that at least 10% of their patients are suffering from mental health issues and provide medication and forms of therapy to these patients (WHO). This efficiency comes from recognizing the core challenge of limited mental health care specialists and training non-specialist emergency workers to use tools such as The mhGAP Humanitarian Intervention Guide (Picot).

Creating stress-reducing environments

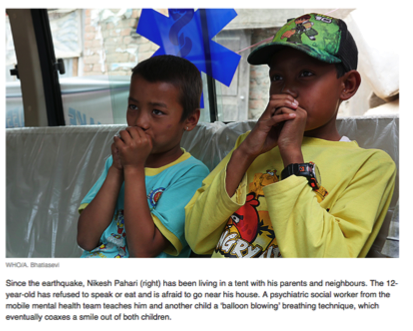

Within the taxing environment of disaster recovery, creating a sense of normalcy is highly beneficial for mental health (Friedman). These environments range from yoga led by community health workers and “child-friendly spaces” created by organizations like UNICEF to spontaneous, organic forms of stress reduction, like children playing soccer and families praying together (International Medical Corps).

Women practice yoga during a support group Photo Credit: Mental Hospital Lagankhal

Women practice yoga during a support group Photo Credit: Mental Hospital Lagankhal

Children playing in a UNICEF Child Friendly Space Photo Credit: UNICEF Canada

Children playing in a UNICEF Child Friendly Space Photo Credit: UNICEF Canada

Long term:

Collaboration between Biomedical and Traditional Medicine

In her article about demand and access to mental health services in Nepal, Natassia Brenman suggests that it is key for biomedical care providers to work collaboratively with traditional healers (Brenman) . This addresses the core challenge of fragmentation. One approach that she suggests is training traditional healers to recognize certain problems and refer them to mental health services. The approach must be used with caution, however, to avoid undermining traditional healers by suggesting that their approaches cannot take on the toughest cases.

Integrating Mental Health Care into Primary Health Care

One way to increase the number of people screened for, and subsequently treated for, mental illness is to integrate basic mental health care screening into primary care settings (WHO). This can also help reduce the stigma associated with seeking help for mental illness.

Exemplars

While there are dozens of organizations doing outstanding work we decided to highlight three organizations that are working to respond to the core challenges of invisibility of mental illness within Nepal, fragmentation of the mental health care system, and the invisibility of mental health in terms of international aid.

Photo Credit:Tributaries International

Nepali Internal Invisibility: Koshish

This NGO was established with the goals of eliminating stigmas, increasing awareness of mental health issues, and advocating for public policy to improve mental health. This addresses the issue of the invisibility of mental health issues in Nepal on multiple levels. First, they help to organize support groups run by Nepali people in order to reduce the invisibility created by stigma. Their work also makes mental health more politically visible. Notably, their efforts have motivated the Government of Nepal to integrate mental health into the Nepal Health Sector Reform Plan-II for the years 2010-2015. Finally, by increasing awareness, Koshish aims to create a community understanding that mental illness is not something that affected individuals or their families should be ashamed of. This reduces the social suffering and invisibility of patients and their families as options besides concealing the mentally ill are opened (Koshish).

Fragmentation: Transcultural Psychosocial Organization (TPO)

TPO’s approach to mental health care addresses the core challenge of fragmentation by using a layered system with forms of complementary support. Their approach reduces the gap between biomedical interventions and cultural understandings by strengthening community and family support. Since the earthquake, they have launched a hotline service staffed by trained psychosocial counselors to provide services to people who are either geographically isolated or cannot afford consistent treatment. This reduces the discontinuity of care by giving patients agency to seek support as needed. They have also collaborated with the WHO, the Government of Nepal, and the Ministry of Health and Population on a program that prepares Nepali psychiatrists to train primary health workers responding to post-earthquake mental health problems. This collaborative work is exemplary for its integration with the government. TPO helps strengthen, coordinate, and centralize the work of NGOS and the government (TPO).

Figure Credit: TPO

International Aid Invisibility: The World Health Organization (WHO)

As a large-scale international NGO, WHO has the capacity to bring previously neglected issues to the forefront of global conversation. Through large scale research projects to estimate the burden of disease, the WHO has not only identified mental health as a leading cause of years lived with disability, but also called attention to social costs of mental illness (WHO). In post-earthquake Nepal, the WHO has provided key guides for focusing relief efforts so that mental health is not neglected (WHO) as well as strategies for making the most of the available resources to provide care (WHO).

Core Readings:

- Nepal Earthquakes 2015: Desk Review of Existing Information with Relevance to Mental Health & Psychosocial Support: A comprehensive review of Nepal’s culture, mental health infrastructure, and humanitarian context.

- Rapid Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Situational Assessment: A summary of the identified needs and existing services following the earthquake.

- Navigating Diagnoses: Understanding Mind-Body Relations, Mental Health, and Stigma in Nepal: A more in-depth background on Nepali concepts of the self and mental health.

Other resources:

- mhGAP Humanitarian Intervention Guide: Strategies to make the most of limited biomedical resources and utilize non-specialists in diagnosing and treating mental illness

- Building Back Better Sustainable Mental Health Care after Emergencies: Case studies about how to see and seize opportunity in crisis to improve mental health care systems

- A mini-documentary depicting the mental health situation in Nepal pre-earthquake

Discussion Questions

- What aspects of developing mental health care infrastructure in Nepal do you think can be translated to other contexts (countries, communities, cities, etc)? What are the challenges of translating a program developed in Nepal to a different context (countries, communities, cities, etc)?

- What are your ideas about how to reduce stigma around seeking treatment for mental health? What can we learn from Nepal that could be applied in our own lives in the US?

- Might biopower further stigmatize mental health by delegitimizing traditional healers? How so? How could this be avoided?

- Construct a case to convince the Nepali government that more governmental funds should be allocated to mental health resources. In other words, why should the government invest any funds in finding solutions for these issues?