Abstract:

Nepal has a health care system that is complicated by access, affordability and availability–issues that were magnified after the devastating earthquake of April 2015. For our project, we chose to focus on the rural Dolakha district, an area that was hit particularly hard by the earthquake. However, as a smaller district, it is not prioritized by many aid organizations and thus faces even greater challenges in rebuilding its healthcare facilities.

We chose to portray the historical background of Nepal’s healthcare system, the chronic and acute “core challenges” that it faces, as well as the significance of focusing on healthcare infrastructure in Nepal, through two fictional stories of Nepali citizens navigating the healthcare delivery system. While our first story focuses on the chronic problems in healthcare infrastructure, and the second story reflects acute problems that arose from the earthquake, both demonstrate how inadequacies in healthcare infrastructure affect both quality and delivery of care, and thus the health and well-being of Nepali citizens. We also propose some potential interventions that could be implemented to improve healthcare infrastructure in Nepal, as well as an example of an organization currently working on these improvements in Dolakha.

Dolakha, one of 75 districts in Nepal (https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4c/Dolkha_district_location.png)

Note: these stories are not based on actual people’s lived experiences and were only developed in order to better represent the range of experiences and challenges facing the Nepal people in accessing healthcare for issues such as TB and traumatic injuries before and after the 2015 Earthquake respectively.

Maya: A Story of Navigating TB Treatment in Pre-Earthquake Nepal

Meet Maya, a 35 year old Nepali woman with two children and a husband living in Dolakha, a small rural district southeast of Kathmandu. Maya and her husband, Kamal, grow medicinal herbs which Kamal uses in his Ayurvedic practice.*

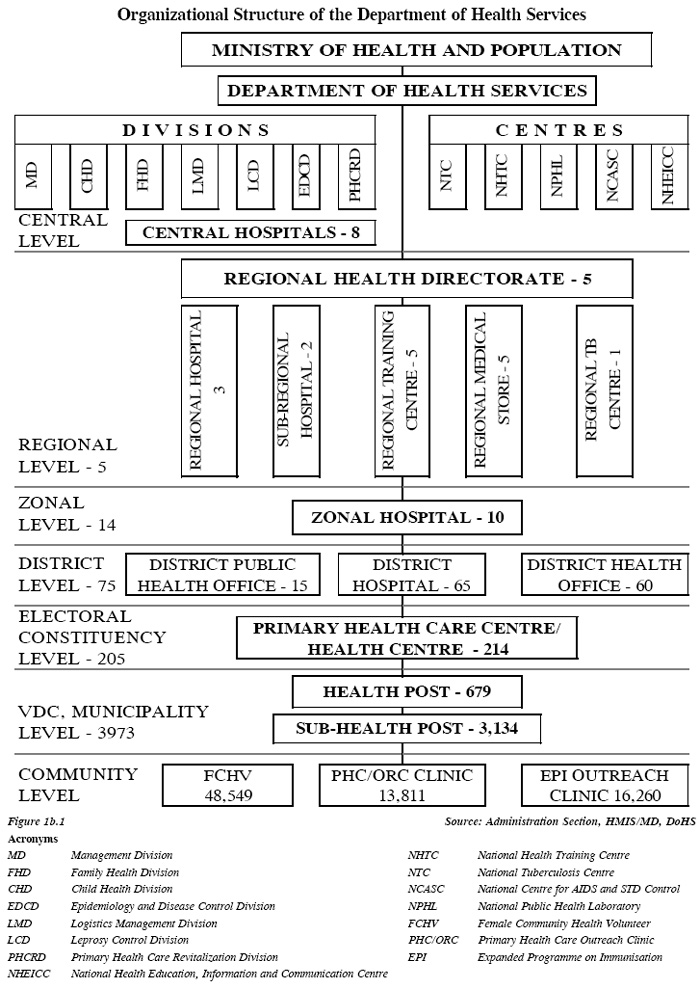

In the summer of 2013, Maya began to experience a persistent cough, fatigue, fever, and loss of appetite. Her husband initially suggested that these symptoms might be due to a disruption in her diet and sleep schedule and recommended that she take an herbal remedy of crushed gooseberries and honey to drink every morning. After one month of this treatment, however, Maya’s symptoms were only getting worse, so the family decided to take the advice of their female community health volunteer and take time away from their farm work to go to a local sub-health post (there are 3,134 sub-health posts scattered across Nepal) (1).

A sub-health post in Nepal (http://www.kullabs.com/class-10/environment-population-and-health-10/community-health-1/health-services-available-in-nepal)

Organization Structure of Nepal’s healthcare infrastructure (http://dohs.gov.np/about-us/organization-structure/)

Community health volunteers are the first line of health care in rural parts of Nepal where there are no doctors. They have basic health care training through the Ministry of Health (2) and play a vital role in health education campaigns and referrals. According to the Ministry of Health, there are over 48,500 community health volunteers nationwide (3).

Female Community Health Care Volunteers in Nepal (http://blog.usaid.gov/2011/01/accounting-for-better-health-in-nepal/)

At the local sub-health post, Maya was seen by a Community Medical Assistant who has slightly less schooling than a community heath worker as they are only required to have up to a grade eight education (4). Based on her symptoms, the CMA believed Maya might have TB. However, the sub-health post did not have the capabilities to test for TB, so Maya was referred to the Gauri Shankar General Hospital. Maya was fearful of the length of her journey to the hospital through the mountainous, but she made the three hour walk. Gauri Shankar General Hospital, has a pharmacy, a surgical ward, several treatment rooms, and 15 beds. This hospital treats approximately 30,000 patients a year (5) There are 65 district hospitals in Nepal. Here, Maya had to wait for six hours to be seen by one of the general practitioners who is on rotation and spent less than 10 minutes with her due to number of patients waiting to be seen. For this consultation, Maya paid a small fee which, thankfully she was able to cover, though this is not the case for everyone and can act as a barrier to accessing care.

The building and ambulance of the Gauri Shankar General Hospital (www.nepalmed.de/ENG/projects_dolakha.html)

At Gauri Shankar, Maya was diagnosed with TB after receiving a blood test and was sent home with TB medication for one month and told to pick up her next month’s supply from her local sub-health post when she ran out. During this treatment, to ensure adherence, the community health volunteer observed Maya taking the pills every day. Maya was relieved to hear that this treatment was paid for entirely by the government. The program Maya was put on is the DOTS program (Directly Observed Treatment Short-course) which was implemented in all 75 districts of Nepal in 2001 (6) and is regularly enacted at the sub-health post level after diagnosis. This program is important due to the high prevalence of TB in Nepal, which affects approximately 153 out of 100,000 people, with a mortality rate of 17 out of 100,000 (7). One month later, Maya was feeling better and returned to the sub-health post to refill her prescription however she was told that a recent outbreak of TB in Kathmandu has made it difficult for medicine to be delivered to the clinic and other sub-health posts. For this reason, Maya was unable to continue her treatment and was asked to return to the sub-health post in another month. Next month though, due to the monsoon season, the roads to the sub-health post are impassable and she had to delay treatment for an additional month.

Nepal Monsoon in 2014 (http://www.dw.com/en/dozens-die-in-nepal-monsoon-disasters/a-17858031)

Two months since her last dose of TB medication, she was finally able to return to the sub-health post and pick up new medicines. After a month of returning to the regulated TB treatment schedule, Maya was concerned as she was not seeing any improvement and believed her symptoms were worsening. She then returned to the sub-health post where she was referred to the district hospital again as they suspected she had multi-drug resistant TB (MDRTB).

While the doctor believed that Maya might have MDRTB, because the hospital lost the support of Kathmandu Model Hospital in 2014 (8) and Nepal Med, a German NGO in 2015, one of 445 NGOs in Nepal, (9) they now had very limited supplies, dignostic equipment, and medicines and were unable to deal with MDRTB. For this reason, Maya was referred to the National Tuberculosis Center (NTC) clinic outside Kathmandu.

48 National Tuberculosis Center in Nepal (http://www.nepalntp.gov.np/index.php?view=gallery&album=March+24%2C+2013-+World+TB+Day&p=4)

The doctors there started her on the DOTS PLUS program to manage her MDRTB. The DOTS-Plus program was started in Nepal in September 2005 (10) and there are now five main treatment centers and 16 sub-centers in Nepal that are able to treat MDRTB (11).

This treatment was also paid for entirely by the government and she received injections six out of seven days of the week and had to take 16-18 pills a day. (11) For the next eight months, Maya stayed at a hostel facility provided by the National Tuberculosis Program while she received treatment, during which time her symptoms improved and she was eventually sent home.

As we can see, Maya faced many obstacles in battling her MDRTB in Nepal’s health care infrastructure. One of the most significant challenges was having to leave her family for an extended period of time due to the lack of advanced treatment facilities near her home. Without her own vehicle or affordable and reliable public transportation, Maya was not able to return home until after her treatment was finally completed at the NTC clinic outside of Kathmandu. Other obstacles Maya faced included transportation costs, difficulty traveling due to weather, lost wages while she was away from home, and unstable drug supply chains which made accessing drugs difficult. Although Maya had access to a local clinic near her home, it did not have the resources to diagnose or treat her MDRTB, a disease which many Nepalis suffer from, but few are properly diagnosed with, and even fewer are able to receive the proper treatments for. Another obstacle Maya faced was at Gauri Shankar District Hospital where their capabilities were greatly inhibited after an NGO they relied on left. Nepal has the support of many NGOs; however this aid is constantly fluctuating and is poorly coordinated. Because of its limited resources, Gauri Shankar’s supply of medicines can vary with the demands of medications in other areas (for example, the densely populated city of Kathmandu) which in the case of TB can lead to MDRTB if treatment regimes are not fulfilled.

Sohan: A Story of Navigating Surgical Care in Post-Earthquake Nepal

Meet Sohan, a 23 year old man who lives in Dolakha. On April 25, 2015, Sohan was injured in the magnitude 7.8 earthquake that devastated Nepal–as he was fleeing from the collapsing factory building where he worked, he fell and was struck by debris. After the earthquake tremors subsided, he and many of his injured co-workers awaited treatment from local emergency relief workers while the non-injured continued to pull people out of the rubble. Upon initial assessment from a local emergency relief worker, Sohan was told that it appeared he had broken his back based on the significance of his pain, and that it would most likely require surgery, however his injuries were not considered severe enough for emergency personnel to treat him right away. Normally, Sohan could have visited Gauri Shankar General Hospital’s surgical ward; however, the earthquake damaged or destroyed 87% of Dolakha’s healthcare facilities, including the district hospital in Gauri Shankar. Initially after the earthquake, Gauri Shankar Hospital was made up of a makeshift collection of tents with one tent for birthing and another for surgery (12).

Staff from Gauri Shankar Hospital attend to injured patients on the grass outside the hospital several days after the earthquake (https://www.facebook.com/PlaninAsia/photos/pcb.900339543345021/900337863345189/?type=1&theater)

Gauri Shanker hospital tents in Pakhalati, Nepal, May 21, 2015. (Peter Bregg for National Post) http://news.nationalpost.com/features/aftershock-heres-how-nepal-is-coping-after-two-earthquakes-left-nearly-9000-dead-16800-injured

After a while, care was able to return to the hospital, although the structure remains compromised.

A cracked wall in Gauri Shankar Hospital after the earthquake (https://planasia.exposure.co/this-mothers-day-meet-the-new-moms-after-the-nepal-quake).

It is currently only staffed by one 29 year old doctor, Binod Dangal, who sees approximately 60 patients per day and works 24/7 (13). This is now the only place the injured can get surgery in the nearest four or five districts. (14). This amazing work ethic demonstrates the extraordinary resiliency and dedication of Nepalis to helping their communities recover from this tragedy.

Dr. Dangal providing treatment to earthquake victims (https://planasia.exposure.co/this-mothers-day-meet-the-new-moms-after-the-nepal-quake).

Fortunately, many organizations have stepped up to help with relief efforts in the region. One such NGO, Possible (a partner organization of Paul Farmer’s Partners in Health), seeks to rebuild Nepal’s healthcare infrastructure with new, earthquake-resistant facilities. Possible has described Nepal’s situation as “acute on chronic”; in other words, the acute crisis of the earthquake hit an already weak healthcare system (15). Thus, the organization seeks to implement a new “durable healthcare model,” in which the Nepali government will pay Possible to deliver care to the poorest Nepali citizens (15). The intended structure of Nepal’s new healthcare system will follow a “hub and spoke” model, which features a public hospital as the central “hub”, surrounded by local primary care clinics closer to individual homes, which serve as first step in treatment (15). Community health workers would serve as liaisons between the clinics and individual homes and communities. Goals for the durable healthcare model include the delivery of care for under $50 per person, as well as improvement of 6 main health outcomes: surgery access; follow-up; use of outpatient services; family planning; equity; and safe births. So far, Possible has treated 276,050 patients since it emerged in 2008, and they are currently trying to construct 21 health care clinics by the end of 2015 as a means of short-term relief (15). Possible is currently in the early stages of rebuilding in Dolakha – the first phrase (through December) will be the immediate prefab construction for damaged facilities, solar electricity installations, and supplies systems improvements.

Destroyed health clinic in Dolakha (https://medium.com/@possible/rebuilding-the-healthcare-system-in-nepal-s-dolakha-district-82fd6bc8298f)

Although Nepal is still in the early stages of rebuilding, some facilities have already been repaired in Dolakha, such as Gauri Shankar’s surgical center. The doctors there were able to perform an X-ray on Sohan, revealing that he had fractured two vertebrae in his spine and would require surgery. He was then moved to the surgical ward for an operation. The operation proved successful, and Sohan was able to make a full recovery.

Interventions:

While potential interventions for the issues discussed in Maya’s story to improve Nepal’s healthcare system involve tackling the chronic issues with infrastructure, the interventions for the issues Sohan encounters deal with addressing the acute problems that arose from the recent disaster. Some interventions which could help to address some of the challenges Maya faced include strengthening infrastructure such as medicine supply chains, creating reliable and cheap public transportation or reimbursing patients for the cost of their transportation to the healthcare facility. Improvements in drainage and road systems could also help to ensure reliable transportation during monsoon season. In addition, expansion of specialty programs such as MDRTB treatment centers to rural areas could increase access to such services and decrease the amount of time and money lost by patients who are currently required to travel great distances and stay there for long periods of time during their treatments. Many of the interventions for problems witnessed by Sohan after the earthquake focus on Farmer’s “staff, stuff, and systems” which need to be in place for a strong healthcare system to exist. In particular in post-earthquake Nepal, some of the resources that could help to rebuild and assist Nepal have been stunted by taxes the country is placing on foreign aid (16). If the government were to lift these taxes on aid, this could dramatically improve health outcomes in Nepal moving forward. In both stories, increased coordination of the countless NGOs in Nepal could help ensure that the care people depend on is equitably distributed and can be relied on.

Discussion Questions

- The relief organization Possible is currently focusing its efforts on Dolakha, a relatively small district that was hit particularly hard by the earthquake. Do you think that NGOs should prioritize these smaller districts like Dolakha, or focus their immediate attention and resources on larger, more urban areas like Kathmandu, where they could potentially reach more people?

- Rebuilding healthcare infrastructure requires more than just construction of healthcare facilities. What other structural components are required for an effective healthcare delivery system?

- How can Nepal’s government ensure that its new healthcare system is serving Nepali citizens effectively and equitably? What might be some metrics that could be used?

- Imagine Maya contracted MDR-TB after the implementation of Possible’s new durable healthcare system. How might her story be different?

Additional Suggested Readings and Resources:

The following video explains some of the challenges facing rural Nepalis who are seeking health care after the earthquake. This video highlights one of the temporary medical clinics set up by the Red Cross while local hospitals are still not functioning. It also touches on some of the transportation issues exacerbated by the monsoon season.

Aftershock Nepal: http://news.nationalpost.com/features/aftershock-heres-how-nepal-is-coping-after-two-earthquakes-left-nearly-9000-dead-16800-injured

Government of Nepal Ministry of Health and Population Department of Health Services Organization Structure: http://dohs.gov.np/about-us/organization-structure/

Possible’s Website: http://possiblehealth.org/

* We wanted to acknowledge the presence of Ayurvedic medicine in Nepal as it is an important part of the healthcare landscape but we wanted to focus primarily on the biomedical healthcare system due to the limited space we have. For more information on Ayurvedic medicine you can read: Healing Elements: Efficacy and the Social Ecologies of Tibetan Medicine by Sienna Craig.

Works Cited:

1. “Organization Structure | Department of Health Services.” Department of Health Services Organization Structure Comments. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Aug. 2015.

2. “National Female Community Health Volunteer Program Strategy.” Advancingpartners.org. Government of Nepal Ministry of Health and Population Department of Health Services Family Health Division, n.d. Web.

3. “Organization Structure | Department of Health Services.” Department of Health Services Organization Structure Comments. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Aug. 2015.

4. Sienna Craig, PhD., Associate Professor of Anthropology, Dartmouth College

5. “DOTS Programme in Nepal.” Creationumesh. N.p., 19 July 2014. Web. 18 Aug. 2015.

6. “Hospital OS: News And Media.” Hospital OS: News And Media. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Aug. 2015.

7. “Nepal: WHO Statistical Profile.” World Health Organization. World Health Organization, Jan. 2015. Web.

8. “Dolakha Hospital – Nepalmed – English Language Version.” Dolakha Hospital – Nepalmed – English Language Version. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Aug. 2015.

9. “Medchrome.” Medchrome. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Aug. 2015. http://medchrome.com/extras/facts/health-system-nepal/

10. “DR TB Management.” National Tuberculosis Center –. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Aug. 2015.

11. “MDR-TB Scale up.” Tackling MDR-TB in Nepal. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Aug. 2015.

12. “Aftershock: Here’s How Nepal Is Coping after Two Earthquakes Left Nearly 9,000 Dead, 16,800 Injured.” National Post Aftershock Heres How Nepal Is Coping after Two Earthquakes Left Nearly 9000 Dead 16800injured Comments. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Aug. 2015.

13. “Home | Possible.” Possible Home Comments. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Aug. 2015. http://possiblehealth.org/

14. “As Dust Settles on Nepal Quake, Pregnant Mothers Look for Hope in New Lives.” Stories by Matt Crook. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Aug. 2015.

15. “Home | Possible.” Possible Home Comments. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Aug. 2015. http://possiblehealth.org/

16. “Earthquake Aid: Tensions Rise as Nepal Imposes Taxes on Relief Materials- Nikkei Asian Review.” Nikkei Asian Review. N.p., 5 June 2015. Web. 25 Aug. 2015.