Abstract

Identity in Nepal is heavily centred on a combination of religion, ethnicity and caste. After Nepal’s unification, the 1854 “Muluki Ain” civil code assigned every person a sub-caste and enshrined the hierarchical rules of caste in law, including restrictions on marriage and occupation. This made social mobility near impossible and facilitated institutionalised social, political and economic discrimination towards low-caste people. Though caste-based discrimination is now illegal, the caste structure remains deeply ingrained in many people. The earthquakes which struck Nepal in April and May, 2015, highlighted the stark inequalities of the system: proportionately higher numbers of low-caste people were displaced; there were instances of unequal distribution of healthcare and aid packages; and there were fewer low-caste politicians, relief volunteers and doctors who could advocate for the needs of the caste-oppressed. However, in some hard-hit areas caste seemed to become invisible in the wake of the disaster. In order to move towards a more equal society, low-caste people need to be given a social and political voice; initiatives to combat social stigma must be implemented; and relief organisations should not turn a blind eye to caste when delivering aid.

- Background and Historical Context of the Caste System

- Significance Post-Earthquake

- Core Challenges

- Possible Interventions

- Exemplars

- Additional Readings and Resources

- References

Background and Historical Context of the Caste System

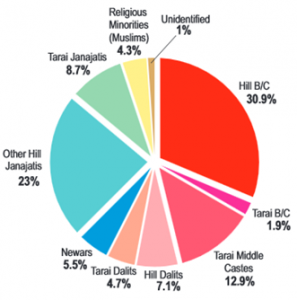

Hindu Origin: Caste is a system of social stratification traditionally associated with Hinduism, which in Nepal has also become closely entwined with ethnicity. Hinduism has a long history in Nepal: even the Buddha, born within the modern boundaries of the country, was born a high-caste Hindu (1). Hinduism, and therefore the caste system, was imported in waves over the course of centuries by Indo-Aryan invaders and refugees; they established kingdoms in central Nepal, thus turning many indigenous ethnic groups (known today collectively as Janajatis) back from Buddhism to Hinduism. In 1768, the Gorkha king Prithvi Narayan Shah unified the many Nepali ethnic groups, including the predominantly Buddhist Sino-Tibetan mountain tribes, into a single country (2). Today, Nepal is officially the world’s only Hindu state (3); roughly 81% of its citizens identify as Hindu, with Buddhists making up about 9% (4).

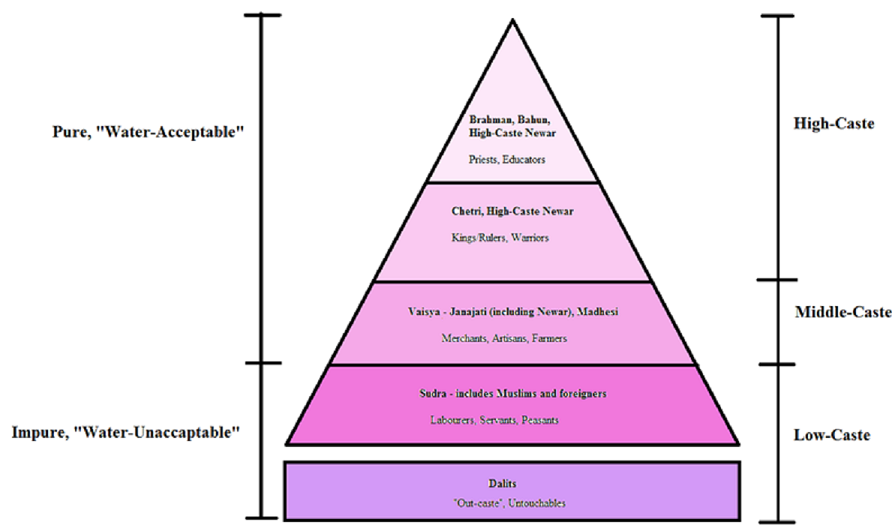

How does the caste system work? In the broadest sense, there are four castes, or varnas, each characterized by relative degrees of ritual purity and social status: the purest and most prestigious varna is the Bahun (or Brahman), who were traditionally priests, scholars and educators; next comes the second high caste, the Chetri, once regarded as warriors and rulers; the last “pure” caste is the Vaisya, which traditionally included merchants, farmers and craftspeople. The fourth varna, considered low-caste and “impure”, is the Sudra, reserved for labourers and servants, who were subordinate to the other three castes. There is an additional, fifth category, whose ‘out-caste’ members are called Dalits: they are not only impure but also physically “untouchable,” the lowest of the low, assigned the tasks too polluting for even the Sudra to perform, such as sweeping.

A Complicated System. The Nepali caste system is incredibly convoluted; even native Nepalis make mistakes. To generalize the classifications: each ethnic group is assigned to a specific varna. The high-caste Brahman and Chetri are comprised almost exclusively of people of Indo-Aryan descent; foreigners and minority religions such as Muslims are deemed Sudra; most other ethnicities fall under Vaisya, Sudra or Dalit. Further complicating matters, certain ethnicities such as the Newar have their own internal caste structures, running the gamut from Brahman to Dalit, and there is disagreement between different ethnicities about caste ranking on a national scale. Therefore, regional context must be taken into consideration. For a more in-depth view of the system, see our Additional Readings and Resources section.

Caste Day-to-Day: Caste governs every aspect of life from birth to death. It is the primary determinant of social status: since it is endogamous (i.e. a person is required to marry within her caste) and inherited patrilineally, social mobility is extremely difficult. Caste is often correlated with class and socio-economic status, but the two are not always linked. Caste was solidified as an ontological phenomenon in 1854 with the introduction of the “Muluki Ain” civil code, which formalized the rules of caste within the legal system (7). No one was exempt, regardless of religion, ethnicity, even nationality (non-Nepalis are allotted “low-caste but touchable” status). Ritual purity was emphasized as being of fundamental importance. For example, the Muluki Ain codified commensality (i.e. who was permitted to eat with whom, and what foods members of different castes could eat); who could accept water from whom (e.g. a Chetri cannot accept water from a Dalit); and instituted a system of punishment for violating caste rules that fell most harshly on those of lower castes. Moreover, from now on a person’s caste and occupation could be instantly pinpointed based on her family name.

In 1963 the Muluki Ain was revised to make “untouchability” illegal and recognize all Nepalis as equal under the law, and in 2011 caste-based discrimination was finally criminalized (8). However, the repercussions of the Muluki Ain are still keenly felt today: caste is among the primary vehicles for discrimination and structural violence in Nepal.

Significance Post-Earthquake

Ongoing structural violence of caste: Recent changes in the law which criminalise caste-based discrimination have so far had little impact on the pervasiveness of caste. Although caste is no longer tied to socio-economic status and occupation, low-caste people typically have higher poverty rates, less access to healthcare, and are less educated – especially Dalits. Some communities reject Dalit presence in hospitals and schools altogether, since contact with them renders a high-caste person temporarily “impure.” This structural violence leads to higher morbidity rates, impacts job prospects and earning power, and prevents appropriate levels of political representation among low-caste people, since there are not enough qualified candidates. According to Shreya Shrestha, a Nepali-born student at Geisel Medical School, “Caste has become intrinsic” (9). Moreover, she said that different castes still tend to self-segregate, especially outside major cities like Kathmandu, and that untouchability is still widely practiced, especially at times of ritual significance.

Problems post-earthquake: The internalization of the caste-system served in some instances to marginalize the needs of low-caste people in the face of disaster. Already exposed to lower standards of healthcare, these people were often offered help last although their need was generally greatest – more low-caste people lived in poorly constructed houses, which collapsed. The majority of Nepali doctors and volunteers were high-caste, so sometimes prone to prioritize high-caste victims over Dalits. This would be easy to do, as Shreya Shrestha says, since a native Nepali can easily identify which caste someone belongs to based on their facial features, style of dress, accent and last name (11).

People from many different sub-castes were displaced by the earthquake and have had to move into relief camps. This raises issues of purity, for example the purity of the hearth: is it acceptable in a disaster zone to accept water and food from a volunteer who is of a lower caste? Living so close to Dalits, is it feasible to maintain “untouchability”? Shreya Shrestha’s experience with relief efforts suggests that the normal rules of caste were temporarily suspended under such conditions. Aid agencies have also been careful to provide foods that are acceptable to eat for all castes, thus showing good cultural sensitivity.

Core Challenges

Invisibility of the Caste System: Finding information on the caste system in Nepal has proved difficult because discrimination based on it is formally outlawed. The Government of Nepal National Planning Commission recently put forth a Nepal Earthquake 2015 Post Disaster Needs Assessment in which caste and social vulnerability of lower castes received no mention. Caste is inherently subjective; information for this site was gathered from an interview with a high-caste, ethnically Newar Nepali immigrant to the United States, Shreya Shrestha, who was present during the May earthquake, as well as outside sources like NGOs, opinion editorials, news resources, and needs assessments by organizations like the World Bank. We recognise that our work is biased; more interviews with Nepalis from different castes and ethnicities would have made our analysis more comprehensive.

The International Conference on Nepal’s Reconstruction posted the National Planning Commission’s “Post Disaster Needs Assessment 2015” to their social media sites. (12)

Discrimination in Distribution: There are many claims from NGOs and awareness groups stating that relief has been distributed unequally between castes post-earthquake, with Dalits, Janajatis, and Madhesis experiencing the worst victimization. According to reports compiled by Amnesty International and the International Dalit Solidarity Network (IDSN), Dalits in particular have experienced willful negligence from relief workers in the distribution of emergency supplies. This is often influenced by members of higher castes with political connections who are able to manipulate the situation to concentrate limited resources toward themselves (such as, for example, using means of influence to bump one’s name higher on a distribution list). These dynamics are facilitated by the fractured political organization of Nepal in the post-2006 era of the interim constitution: it has given rise to a number of mini-governing bodies which exercise primary decision-making authority over a number of rural communities predominantly composed of lower castes that have little to no representation in the governing bodies themselves. Thus, access to resources was reduced for those who suffered the greatest damage from the earthquake, since lower-caste individuals already tend to occupy disproportionately vulnerable positions in society.

Infrastructural Vulnerabilities: Dalits and Janajatis in both rural and semi-urban environments are more likely to live in houses constructed from stone and mud, which collapsed due to the quake’s tremors. By contrast, around 80% of concrete dwellings, generally occupied by higher castes, stayed intact. These unstable homes were also built in perilous locales: on insecure slopes, exposed to rockfalls, and along riverbanks (13). Moreover, quantity of debris is associated with immediate reductions in food security, since materials mix with and contaminate existing food supplies.

Breakdown of Tamang death rates per district. (13)

Close-Up–The plight of the Tamang people, an ethnic sub-group associated with the Janajati caste, vivifies the connections between location and infrastructural vulnerability: an estimate released in early July from the Ministry of Home Affairs identified that over half of the 607,212 buildings damaged by the quakes were situated in Tamang-dominated areas. Tamangs composed 34% of the estimated death toll from both earthquakes at this time, the highest proportion of those killed in the Sindhupalchok district northeast of Kathmandu, which bore the brunt of the tremors. The location of the Tamangs directly contributed to their high death rate. Less than 40% are able to access health clinics within 30 minutes of walking. Lack of education compared to less-discriminated castes hampers benefits the Tamangs would otherwise gain from proximity to the nation’s capitol (13).

Human Rights Violations:

Dalits are often vulnerable to human rights violations that are not justly addressed by the government or police administration. Despite the official outlawing of caste-based discrimination, there is no legislation in place to ensure that law enforcement agencies deliver equitable and just responses to formally filed complaints. Thus, those who commit injustices against Dalits will likely never face prosecution. This has created a culture in which the majority of Dalits have lost faith in the government’s espoused commitment to steward their rights, leading them to accept the physical violence and substandard health conditions that they systematically endure as an unpreventable part of the social order – a form of symbolic violence (14). To this effect, many have ceased lodging complaints. The earthquake created conditions that exacerbated this situation, manifested through those whose trust in the government has been further damaged by the unequal aid response and those who have experienced caste-based violence during the quake.

(16)

(16)

Close-Up—Consider the case of Saraswati Sunar, a Dalit whose relief package of tarpaulins and blankets from World Vision was distributed to someone else after the earthquake. Unconcerned for herself, Sunar instead attempted to uncover the location of a similarly absent package marked out for her fellow Dalit neighbor, a mother of eight whose family had been displaced. Yet no sooner had she asked volunteers about the package than three higher-caste neighbors physically assaulted her, fracturing her left shoulder (16). Follow the progression of her unsuccessful attempt to find justice here:

Possible Interventions:

Social Inclusion, Legislation, and the Government’s Response: Bhakta Bishwokarma, president of the Nepal National Dalit Social Welfare Organisation (NNDSWO), points to a way to avoid future uneven aid responses: “For rescue and relief operations in Nepal to be non-discriminatory, Dalits must be consulted and involved in the planning and delivery” (17). In order for an integration of Dalits into discussions of relief to be feasible, the concept of untouchability must be reduced or eliminated from the cultural imagination; otherwise, the taboo associated with forms of mingling will continue to serve as a barrier to the group’s the group’s collective voice. Fortunately, small seeds of such a potential elimination are not unheard of: alongside moments of caste-based violence, the earthquake has also produced moments in which the barriers of the caste system appear to dissolve as people work together to survive and rebuild.

Take the example of Baburam, a Dalit from the Gorkha district who has been volunteering with an NGO called HEADS-Nepal to help people salvage valuables from their destroyed homes. He reports finding camaraderie with his fellow volunteers from higher castes as well as those he aids, never encountering any form of resistance or personal discrimination (18). Shreya Shrestha noted that caste was a non-entity as she carried out relief work. She says that while caste does not disappear completely (salient facial features do often help native Nepalis discern who belongs in which caste), ingrained prejudice vanished to many people in the energies of the crisis produced by the earthquake–she described an overall societal shift to prioritizing the preservation of human life, with equal value assigned to all groups. These cultural moments of widespread humanitarianism provide ample opportunity for an intervention by the government, whose actions could have very tangible consequences for the social order in post-quake Nepal. This intervention would involve enacting and effectively implementing laws that enforced the government’s rhetorical commitment to end caste-based discrimination by delivering penalties to perpetrators and ensuring just recompense for victims, and creating negative incentives for violent behavior while encouraging the altruistic inter-caste interactions that have been seen during relief efforts. Shrestha notes that the goal should not be to eliminate caste entirely; instead, Nepal must acknowledge that caste provides community by facilitating a sense of cultural, ethnic, and religious belonging while working toward the eradication of violence (physical and symbolic), suffering, and vulnerability experienced by lower castes (11).

#DalitLivesMatter has become a phenomenon of twitter activism, indicated by an entire Twitter account and hashtag (19)

Social Media: NGOs like the IDSN, news agencies like the Anadolu Agency, and the International Conference on Nepal’s Reconstruction (ICNR 2015) have active Twitter and Facebook feeds, web pages, and social media petitions that promote efforts surrounding the issue of caste disparity. Many relief groups and individuals have also expanded the use of the new catchphrases #DalitLivesMatter and #DiscriminationinNepal over the last few years, which have become all the more powerful in the face of the worldwide attention Nepal has received after the disaster (19).

Census Information Collection: There is a lack of information on census material on social classifications, but these social distinctions are well-known, according to Shreya Shrestha, based on where a person is from, their ethnicity, and their last name. But gathering data on cultural and ethnic backgrounds could produce more effective hypotheses for targeting caste discrimination (11).

“When we were on the ground, I did not encounter caste at all.” – Shreya Shrestha

Exemplars

- International Dalit Solidarity Network (IDSN): This is a global NGO dedicated to ending issues of caste-based discrimination that, in Nepal, targets human trafficking, bonded labor, inhibited political participation, and social stigma attached to caste. In the face of the earthquake the IDSN has had quite a large presence on social media and advocating for equality in relief efforts. Cooperating with many other Dalit-Oriented organizations, it produced the document Waiting for “Justice in Response” post-earthquake.

- ALNAP and ACAPS: The “Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance in Humanitarian Action (ALNAP) was established in 1997, as a mechanism to provide a forum on learning, accountability and performance issues for the humanitarian sector,” claims their website (20). ACAPS is a similar organization that also hopes to improve “the assessment of humanitarian needs in complex emergencies and crises” (21). Both of these organizations produced assessments of the responses to the 2015 Nepal Earthquakes that placed great emphasis on the effects of caste inequality, in contrast to many local relief efforts.

- Amnesty International: An organization begun by British lawyer Peter Benenson in 1961, Amnesty seeks to expose specific issues of inequality and combat discrimination all around the world. It provided a report that “highlights important areas of concern which […] could have an impact on the success of relief and reconstruction endeavors in Nepal.” Much of Amnesty’s advocacy has focused on equal aid distribution, particularly to “groups who are often the target of discriminatory treatment… including women who head households, Dalits, Indigenous Peoples or people with disabilities” (22).

- Empower Dalit Women of Nepal (EDWON) and Association for Dalit Women Advancement of Nepal (ADWAN): Founded by Bishnu Maya Pariyar, a female Nepali rights activist currently living in the United States, to “enable rural Dalit women repressed by caste and gender to claim their rights and live in dignity” (15), EDWON has worked to implement microfinance groups of 15-25 women from a cross-section of different castes that run their own savings and loan associations to fund small enterprises. These groups are found in Bishnu Maya’s home district of Gorkha and have stood successfully for over a decade, transforming members into change agents in their community. EDWON rallied financial support from independent donors following the earthquakes to create a rebuilding fund that aims to address the gaps, left unchecked by the Nepali government’s slow emergency relief response to rural low-caste communities, in which the 760 women involved in EDWON’s savings groups are caught. EDWON’s Nepali partner, ADWAN, distributed crucial supplies to over 4,000 people in these women’s communities, including “several thousand kilos of food (rice, lentils, potatoes, oil), hundreds of tents, blankets, sleeping mats, and mosquito nets, as well as 150 solar lanterns to keep women and girls safe at night.” Bishnu Maya returned to Nepal personally immediately following the quake to help distribute relief aid to thousands in her native village of Taklung (23). Her battle against caste-based discrimination was the subject of a short documentary released in June that can be viewed here:

(24)

Additional Readings and Resources

- A personal interview with a Geisel Medical School student, Shreya Shrestha, gave this group a great foundational understanding of the current state of the caste system in Nepal and how it has intersected with relief efforts. It is with her consent that we post the following recording of the interview.

- András Höfer’s study of the 1854 Muluki Ain, The Caste Hierarchy and the State of Nepal provides a detailed analysis of Nepal’s caste rules as they were legally defined for over a century; this civil code, now outdated, molded the caste system into the form it holds today.

- For impact statistics and humanitarian aid focus on caste and privilege disparity from a partnership of caste-focused NGOs, see the IDSN Report: Waiting for “Justice in Response”.

- The World Bank’s Unequal Citizens: Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal Summary showcases the findings of a multi-year study of social exclusion in Nepal. It outlines clearly the current impact of caste on life in Nepal.

Discussion Questions

- Will the suspension of normal caste rules experienced at the height of the earthquake lead to a lessening of caste rigidity, or reinforce caste inequalities in the long run?

- The immediate aftermath of the earthquake has created space for discussion and critique of Nepali social structures, which has the potential to lead to change if acted upon swiftly; otherwise, the opportunity may pass when another large-scale event occurs that will take priority in people’s minds. Who will be the most effective agents of change? The citizens of Nepal or the government?

- Do social media movements such as #DalitLivesMatter help create effective international solidarity for issues like caste-based discrimination? Could such solidarity initiate any tangible long-term impacts, or is simply raising awareness valuable enough?

References

Featured Photo: A high-caste man, offered water by a Dalit “water-unacceptable” tailor, is compelled by caste rules to drink it from his hands instead of directly from the container. “Unequal Citizens: Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal, Summary.” World Bank. World Bank, n.d. Web. p58. 26 Aug. 2015. <http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2006/12/05/000090341_20061205151859/Rendered/PDF/379660Nepal0GSEA0Summary0Report01PUBLIC1.pdf>

1. Shrestha, Nanda R. and Keshav Bhattarai. Historical Dictionary of Nepal. USA: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2003. p75. Print.

2. Gellner, David N. Introduction. Nationalism and Ethnicity in a Hindu Kingdom: The Politics of Culture in Contemporary Nepal. Eds. David N. Gellner, Joanna Pfaff-Czarnecka, and John Whelpton. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1997. 3-31. Print.

3. “Constitution of Nepal 1990”. Nepal Democracy. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung – Nepal, 2001. Part 1: Article 4, (1). Web. 26 Aug. 2015. <http://www.nepaldemocracy.org/documents/national_laws/constitution1990.htm>

4. “A Civil Society Parallel Report on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in Nepal.” Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. United Nations Economic, Social and Cultural Committee, 2013. Article 15, p79. Web. 26 Aug. 2015. <http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CESCR/Shared%20Documents/NPL/INT_CESCR_NGO_NPL_15369_E.pdf>

5. “Unequal Citizens: Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal, Summary.” World Bank. World Bank, n.d. Web. p18. 26 Aug. 2015. <http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2006/12/05/000090341_20061205151859/Rendered/PDF/379660Nepal0GSEA0Summary0Report01PUBLIC1.pdf>

6. “Unequal Citizens: Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal, Summary.” World Bank. World Bank, n.d. Web. p17. 26 Aug. 2015. <http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2006/12/05/000090341_20061205151859/Rendered/PDF/379660Nepal0GSEA0Summary0Report01PUBLIC1.pdf>

7. Höfer, András. “The Caste Hierarchy and the State in Nepal: A Study of the Muluki Ain of 1854.” Center for Research Libraries. Center for Research Libraries, 2 Aug. 2010. Web. 26 Aug. 2015. <https://dds.crl.edu/crldelivery/14196>

8. “A Civil Society Parallel Report on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in Nepal.” Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. United Nations Economic, Social and Cultural Committee, 2013. Article 2, p19. Web. 26 Aug. 2015. <http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CESCR/Shared%20Documents/NPL/INT_CESCR_NGO_NPL_15369_E.pdf>

9. Shrestha, Shreya. (2015, August 18). Personal interview. <https://soundcloud.com/nepal-earthquakes/shreya-shrestha-interview>

10. “Waiting for ‘Justice in Response’.” Asia Dalit Rights Forum. Dalit Civil Society Massive Earthquake Victim Support and Coordination Committee, 2015. p6. Web. 26 Aug. 2015. <http://asiadalitrightsforum.org/images/imageevent/1294431538REPORT%20OF%20IMMEDIATE%20ASSESSMENT%20NEPAL%20(1).pdf>

11. Shrestha, Shreya. (2015, August 18). Personal interview. <https://soundcloud.com/nepal-earthquakes/shreya-shrestha-interview>

12. Photo taken 20 August 2015 from: https://twitter.com/NepalDonorConf

13. Magar, Santa Gaha. The Tamang epicentre. Nepali Times. 5 July 2015. <http://www.nepalitimes.com/blogs/thebrief/2015/07/05/the-tamang-epicentre/>

14. Tamrakar, Tek. “Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights.” Feminist Dalit Organization, 2011.

15. Empower Dalit Women of Nepal Mission Statement. EDWON.org. <http://www.edwon.org/>

16. Adhikari, Deepak. Nepal Dalits Discriminated Against for Quake Relief. Anadolu Agency. 12 August 2015. <http://www.aa.com.tr/en/u/572797–nepal-dalits-discriminated-against-for-quake-relief>

17. Report: Dalits short-changed in aid delivery in Nepal. IDSN.org. 29 May 2015. <http://idsn.org/dalits-short-changed-in-aid-delivery-in-nepal/>

18. Nepal post-quake relief: Breaking the caste barriers. World Humanitarian Summit. 29 July 2015. <http://blog.worldhumanitariansummit.org/entries/nepal-relief/>

19. Photo taken 20 August 2015 from: https://twitter.com/hashtag/Dalitlivesmatter?src=hash

20. ALNAPS.org. <http://www.alnap.org/who-we-are/our-role>

21. Lessons Learned for Nepal Earthquake Response. ACAPS.org. 27 April 2015. <http://acaps.org/img/documents/l-acaps_lessons_learned_nepal_earthquake_27_april_2015.pdf>

22. Amnesty International. Nepal, Earthquake Recovery Must Safeguard Human Rights. 1 June 2015. <https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/ASA31/1753/2015/en/>

23.Empower Dalit Women of Nepal – Earthquake Update. Global Giving. <https://www.globalgiving.org/donate/14728/empower-dalit-women-of-nepal/reports/>.

24. EDWON video: “Untouchable.” Join the Light. 14 August, 2014. <https://vimeo.com/103464350>