Why should the student of politics be apprised of the beautiful? This question is answered perhaps obliquely in the Nicomachean Ethics, where the Aristotle remarks that of the four fundamental questions of the study of politics, one is the enquiry into what is “noble [kalon] and just” (NE 1144a12). But this very word, kalon, is the root of much debate, sometimes with acerbic overtones in academic settings that seem otherwise to be bereft of sharp rivalries and accusations and allegations of utter and complete incomprehension of the object, or in this case, the word being examined. Today, I shall endeavour to write about the word ‘kalon’ despite my utter and total lack of Greek, ancient or modern; with this goes any apologies that must be rendered for coming off as a total tool. The question that we are faced with is simple: why is kalon rendered in translations the way it is: varyingly, as noble, just, or good, or nothing but beautiful? Can we truly remove from the scope of Aristotle’s ethical and political thought any concern with aesthetics, and, if this being the case, is such an artificial separation detrimental to how we conceive of politics in practice and thought?

Category: Aristotle

Marginal Notes toward a Politics of Space

Socrates, awaiting his execution in a prison cell in Athens, tells his protégé this nugget of wisdom: “the good life, the beautiful life, and the just life are the same” (Crito, 48b). The just, the beautiful, and the true are intrinsically linked together, for they take their ideal form in the wholly abstract world of forms. In this essay, I do not seek to argue for the nature of beauty, or for aesthetic characteristics of an objective standard of beauty, but only that the current manner in which aesthetic degradation has permeated into life is subversive to the ends of the polis — namely, it actively works to subvert human flourishing, broadly understood — and must be dealt with in the strongest possible terms. The importance that is attached to this subject arises from a strong sense of architectural exceptionalism and the moral character inherent in architecture and in any sort of grand design.

Continue reading “Marginal Notes toward a Politics of Space”

The Acquisitive Life and the Good Life

R.F. Stalley remarks in his introduction to Aristotle’s Politics:

“Disturbingly, however, he [Aristotle] does not disguise the fact that only a limited section of the population will be able to achieve such a life. Many people lack the appropriate capacities, but, in any case, the existence of a city requires that a substantial number of its inhabitants engage in occupations which are inconsistent with a good life. Manual labour and trade not only take up time, but they also render people unfit for the activities which Aristotle sees as worthwhile.”[1]

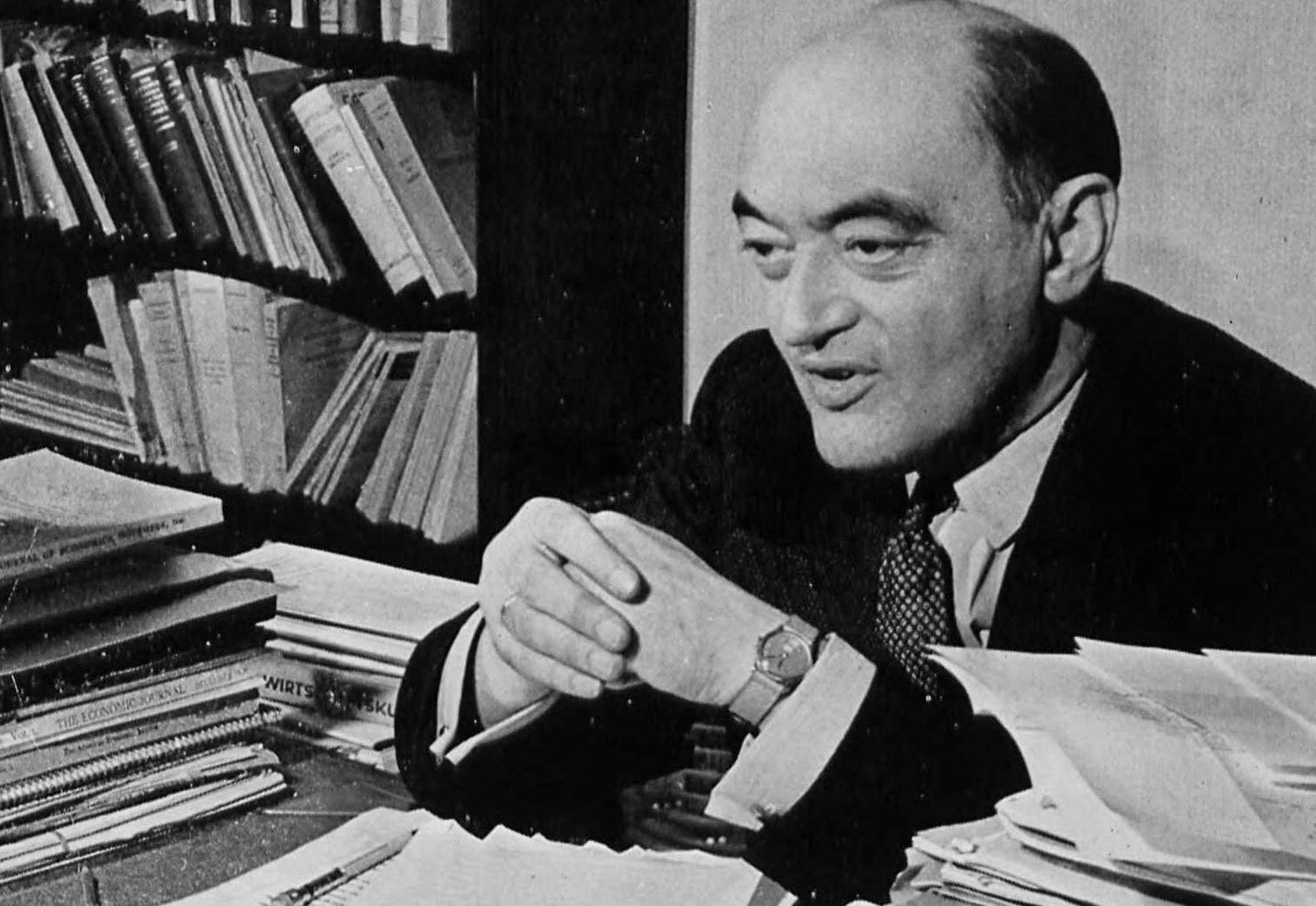

Schumpeter’s Soirée with the Ancients and the Schoolmen

Joseph Schumpeter is the rare economist whose interest and work extends outside of the small, technical field of economic analysis. In his History of Economic Analysis, he looks deep and wide, but of particular interest to us are his comments on the ancient Greeks and Romans, and the medieval Scholastics.1 The book is more widely known for the provocative claim that the man regarded as the father of classical economists was merely derivative of his French brethren — Turgot being the main source of ‘inspiration’ — but that is a claim that I will reserve for examination at another time. For now, of key interest are: {1} the distinction he makes between thought and analysis, {2} the distinctions he draws between Plato and Aristotle, {3} his discussion of the development of the concept of usury alongside the flourishing of industry in medieval Europe, and {4} his discussion of the ‘welfare state’ and its relation to the thought of the medieval scholastics.

Continue reading “Schumpeter’s Soirée with the Ancients and the Schoolmen”

- Joseph Alois Schumpeter, History of Economic Analysis, ed. Elizabeth Boody Schumpeter (London: Routledge, 2006). ↩

Short Note #1: The Importance of Politics

To know man fully is to know first what politics is. Aristotle’s arguments for the importance and primacy of politics still maintain their vitality today. They go as follows.

For Aristotle, “nature … makes nothing in vain” (Politics, 1.2, 1253a8–9). Everything that arises from nature has an end, a telos. Man’s telos is determined by Aristotle by the possession of faculties of speech that go beyond expressions of “pleasure and pain” (1253a12). The Epicureans would like to reduce most things to pleasure and pain, but Aristotle does not: he restricts them to the domain of animals, not humans. Humans use their speech to express more complex ideas; for example, “man alone possesses a perception of good and evil” (1253a16). Man’s ability to converse has an end, and it cannot be realised in solitary existence.

Continue reading “Short Note #1: The Importance of Politics”

Aristotle’s Critique of Plato’s Communism

At the end of the first chapter of Book II of Politics, Aristotle poses the question: Is it “better to remain in our present condition or to follow the rule of life laid down in The Republic?” Aristotle presents a wide range of arguments to combat the particulars of what he perceives to be the result of Socrates’ advocacy for a city that would be fit only for one individual. In 1261a10, he uses the logic of the distinction he makes between polis, household, and individual to assert that the ideal city for Plato and Socrates would mean the destruction of the city because it would set out to erase all difference between its constituents through a rigid ordering of freedom and the rule of the singular and perhaps even tyrannical philosopher-king.

Continue reading “Aristotle’s Critique of Plato’s Communism”

Who was Aristotle?

The historical Aristotle is enigmatic. He does not enjoy the same level of infamy as Socrates, and whilst he is connected with the slightly less enigmatic but grand and popular Alexander, his famous pupil (of that there is no doubt, though there is no certainty as to the contents of his tutelage), he remains a mystery. There are few expressions of his personality, and more information about him comes from rumours and invectives than sources one may consider historical á la Thucydides. My account here is based on my observations whilst reading Carlo Natali’s Aristotle: His Life and School,1 which was the most advanced scholarship I could find and peruse. I will attempt to avoid commonplace observations about him, unless they are inescapable.2