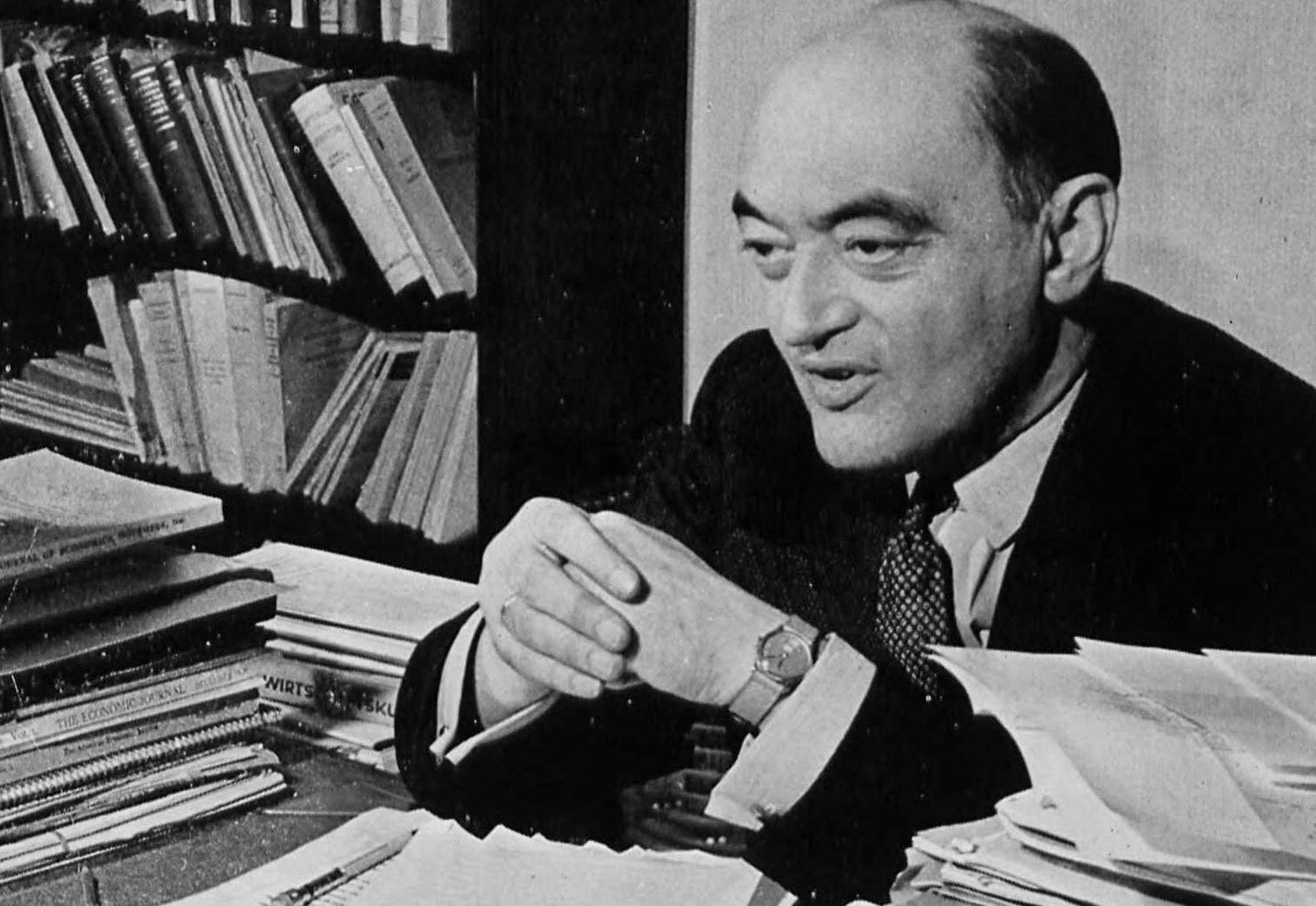

Joseph Schumpeter is the rare economist whose interest and work extends outside of the small, technical field of economic analysis. In his History of Economic Analysis, he looks deep and wide, but of particular interest to us are his comments on the ancient Greeks and Romans, and the medieval Scholastics.1 The book is more widely known for the provocative claim that the man regarded as the father of classical economists was merely derivative of his French brethren — Turgot being the main source of ‘inspiration’ — but that is a claim that I will reserve for examination at another time. For now, of key interest are: {1} the distinction he makes between thought and analysis, {2} the distinctions he draws between Plato and Aristotle, {3} his discussion of the development of the concept of usury alongside the flourishing of industry in medieval Europe, and {4} his discussion of the ‘welfare state’ and its relation to the thought of the medieval scholastics.

Analysis Contra Thought

Schumpeter is a maestro in making distinctions, but unlike The Economist, which has a torrid love affair with lists of three elements, this economist makes distinctions in all sorts of numbers but three.

In any case, the first useful distinction for our purposes is the “distinction between Economic Thought … and Economic Analysis” (49). Everyone thinks about economics, Schumpeter points out, because of the pervasive nature of economic phenomena in our daily lives. In this category is included utterances about economics along the lines of, ‘the fields seem dry for this time of the year,’ ‘there ought to be more of a hustle and bustle in the marketplace,’ or the treasurer complaining of an impending bankruptcy. It is commonplace and does not require much analysis, and Schumpeter confines it to the domain of “economic history rather than to the province of the history of economics” (49). Schumpeter provides an easily accessible example of economic thought, distinguished from economic analysis: “The sacred books of Israel … reveal perfect grasp of the practical economic problems of the Hebrew state. But there is no trace of analytic effort” (49). The Israelites knew the problems that faced them, understood them comprehensively, and figured out how to solve them, Schumpeter points out, but deigned to think analytically about economics. What, then, is economic analysis? For Schumpeter, economic analysis is “the result of scientific endeavour” which can be traced back to the ancient Greeks (49).

What prevented the Chinese or other great ancient civilisations from thinking about economics in an analytical manner? Schumpeter does not gloss over the question but speculates in an informed manner. He admits the possibility that their analytical work could have been lost, but “there is reason to suppose that there was not much of it” in the first place (50).

What led Schumpeter to this judgement? It was the recognition of the effect of practical knowledge, distinct from theoretical speculation, on economic matters. Economics is unique: “common sense knowledge, relative to scientific knowledge, goes much father in the economic field than it does in any other” (50). He continues, in a statement that ought to earn the ire of every professional economist, but not many others: “economic life is the sum total of the most common and most drab experiences” (50). Economic life is banal. It is mundane, repetitive, and oftentimes the product of action necessitated by material factors necessary for sustenance, or the result of a drive for the acquisition of wealth as a substitute for some other inner failing or deep-seated insecurity about oneself. A negligible minority of those involved in economic activity have a formal education in economics, it must be added, even today, despite growing enrolments in economics departments globally today. Economic actors are almost never educated economists, even more so if one looks to the past. Bill Gates most certainly did not have an economics degree (or any degree, for that matter). Success in the economic sphere — the acquisition of wealth — is possible even in the throes of ignorance about the formal lessons of economic analysis. Schumpeter even admits that the study of economics is not instinctually attractive. It lacks temptation. “Nature harbours secrets,” Schumpeter reminds the reader, and those prone to thinking with depth and rigour are more drawn to them, and not to economic life (50).

The next sentence — “Social problems interest the scholarly mind primarily from a philosophical and political standpoint; scientifically they do not at first appear very interesting or even to be ‘problems’ at all” (50) — is more puzzling, especially coming from an economist, than the brief excursus Schumpeter sketches above of what can only be described as the pre-history of economic analysis. This sentence can be understood as such: Schumpeter thinks that we are prone to understanding social issues within the context of the community and within the moral and civil constraints on economic activity. The purpose of scientific analysis, I think, in Schumpeter’s perspective, is the creation of economics as a field of independent inquiry. Though Schumpeter does not lose his morality, like many other economists, and blends his own sense of morality into economics in Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, he chastises St. Thomas Aquinas for his disinterest in economic subjects in his discussion of the Schoolmen, writing:

“St. Thomas, in particular, was indeed interested in political sociology but all the economic questions put together mattered less to him than did the smallest point of theological or philosophical doctrine, and it is only where economic phenomena raise questions of moral theology that he touches upon them at all” (92).

This chastisement has its intended effect in that it brings to head all of Schumpeter’s admiration for St. Thomas and diminishes it to a qualified criticism. ‘Yes’, one can imagine Schumpeter murmuring under his breath, ‘St. Thomas was a great man, a genius, but who needs moral philosophy when we have economics?’ While there is no such record of Schumpeter saying these words, or something like this, his work is tainted by a regular disparagement of moral philosophy that follows some exacting and insightful sketches of the schoolmen.

In any case, I think Schumpeter ought to have drawn a further distinction, one he dismisses half-heartedly in his discussion of the Romans. In the midst of his admiration for the Romans as men of practical wisdom, he has an inadvertent but revealing slip [I would have used Freudian to describe the slip, but I despise Freud, and I most certainly doubt that Schumpeter’s looseness of language had anything to do with sexual promiscuity or desire]. He postulates:

“The doctrine that practical need — and not, as I hold, the lure of intellectual adventure — is the prime mover of scientific endeavour can be put to the test in the case of ancient Rome” (68).

The sentence quoted above has only one end, in light of the following paragraphs. Schumpeter is carefully laudatory of the Romans, and especially the sophistication of their legal system, which he praises in his discussion on the natural law. He puts the doctrine to test, and it appears as though the ‘practical need’ of the Romans appears to have sufficed in the creation and propagation of a wondrous Republic and a somewhat more disappointing and chaotic Empire. Of the Eastern Roman Empire, he remarks that it “survived the Western for another thousand years, kept going by the most interesting and most successful bureaucracy the world has ever seen” (75) — even in the absence of economic analysis by his own admission, of scientific insight into the functioning of the economics. Practical need drove the Romans to the creation of perhaps the most sophisticated system of law that has been in continuous use in some way, shape, or form, from the Law of the Twelve Tables of the Rome of misty time to the very present moment. Or, at least, that is what Schumpeter’s analysis is. I, for one, do not think that the Romans were wholly disinclined toward questions of philosophy, although they maintained the dubious distinction of being a polis that expelled the philosophers and not the poets for some time. Plato would have been aghast, but we must not be. Within the information and the overarching narrative presented to us, it seems as though the sort of complex economic analysis that Schumpeter himself would advocate can arise out of practical necessity only when there is either a desire to understand the world in terms that existing conceptualisations make difficult or impossible, or when there is a desire to examine the world at large and from where economics makes some mutative and putative occurrence, always as the part of a whole and not a separate entity in itself.

Plato and Aristotle

Schumpeter, in his examination of Aristotle, takes the well-trodden path of looking at Plato first. The city of the Republic, Schumpeter admits, “is no more analysis than a painter’s rendering of a Venus is scientific anatomy” (52). On this front, even the most fervent admirer of Botticelli must concede ground to the point being made. Admirable as it is, it is the work of an overactive imagination, not the result of a scientific analysis of the object at hand. Although it reflects the idea of what it seeks to describe, and is recognisable as such, it is always impracticable and best left to the imagination. It has a supernatural draw and always elicits extreme reactions from those exposed to it. But Botticelli threatened to confine his to the flames under the delirious influence of the heretic Savonarola, and Plato admits the impracticality of Kallipolis in the Laws, which is changed considerably. “Chiefly,” Schumpeter notes, “they are compromises with reality” (52).

For all his flights of fancies, Plato is the recipient of much approbation. The first of the laudatory comments is the recognition “of the necessity of some Division of Labour” in Book II of the Republic, which Aristotle carries over into his work (53). The passage he alludes to is at 370c: “The result, then, is that more plentiful and better-quality goods are more easily produced if each person does one thing for which he is naturally suited, does it at the right time, and is released from having to do any of the others.” Socrates, conversing with Adeimantus, has just started on his quest to build, from the ground up, his ideal city. Although Socrates has promised Adeimantus that he will first define what “justice is in a city” (369a), he tries to achieve this in a roundabout way: he wants to build a city from the ground up, and then analyse what sort of justice is possible within it. In this early stage of the conversation, Socrates finds it essential to mention the need for specialisation because, as Schumpeter rightly points out, not because there may be an increase in productivity — though that is most certainly part of Socrates’ calculus — but more importantly, from a “recognition of innate differences in abilities” such that it becomes necessary to permit “everyone to specialise in what he is by nature best fitted for” (53). However, this line of inquiry is only presented en passant, and the focus is shifted to a more important matter, which establishes Schumpeter’s own economic proclivities, and provides the basis for his rebuke of Aristotle. This opportune moment is provided by the development of what Schumpeter terms Plato’s ‘monetary policy.’

Curiously, though, Schumpeter jumps from 370c to 371d without addressing the elephant in the room, demanding attention from its more analysed successor: “There’ll be people who’ll notice this and provide the requisite service — in well-organised cities they’ll usually be those whose bodies are the weakest and who aren’t fit to do any other work.” This passage, at 371c, describes those who buy and sell in the marketplace, because, as Socrates points out, it is unlikely that producers and consumers will congregate in the market at the same temporal span. Those who seek to tide these over engage in what is the lowliest of occupations, for Socrates. The commercial life is only for those who cannot do anything else, Socrates informs Adeimantus, and only the dregs of society ought to engage in it; they are not ‘productive’ members of society, but parasites who are most likely to engage in rent-seeking practices. In any case, Socrates’ visceral aversion to commerce — distinct from production — is visible here, and does not elucidate any reaction from Schumpeter. It is in this context that both Plato’s and Schumpeter’s views on the subject must be addressed.

Schumpeter notes that Plato’s ‘monetary policy’ is based on two different observations: (a) “his hostility to the use of gold and silver” and (b) “his idea of a domestic currency that would be useless abroad” (53). In both cases, they are tied up in more complex tales that ought to be thought of further. It makes Schumpeter’s distinctions between Plato and Aristotle seem less pressing, though I do not intend to say that there are no irreconcilable differences between the teacher and student.

Plato mentions “his hostility to the use of gold and silver” at the end of Book III of the Republic. Socrates is attempting to distinguish between “soldiers” and “money-makers” (415e), and tries to build in safeguards to prevent the former from terrorising the latter. He recognises the important part both play in the polis; but the focus, first, is on the soldiers. After denying them private property and privacy in their private property (416d), Socrates proceeds to endow them with a moderate salary through taxation (416e). But the most important, here, is the denial of precious metals:

“We’ll tell them that they always have gold and silver of a divine sort in their souls as a gift from the gods and so have no further need of human gold. Indeed, we’ll tell them that it’s impious for them to defile this divine possession by any admixture of such gold, because many impious deeds have been done that involve the currency used by ordinary people, while their own is pure. Hence, for them alone … it is unlawful to touch or handle gold or silver.” (416e–417d)

Soldiers ought to live in spartan conditions — and this ought not to be taken entirely without the historical comparison this necessitates, for Socrates’ system for soldiers has some startling similarities. At any rate, the main differentiator here is the Spartan’s ability to own all sorts of property. The guardians, by being denied material luxuries, are denied temptation, and are supposed to be incorruptible. Gold and silver, then, are also means of coercion: the guardian cannot defect, either, because he will have nowhere to go because he does not have the ability to leave. The same can be same about trade, for that matter — to keep the inhabitants of the polis within it, their universal tokens of exchange, accepted far and wide, are taken from them, and they are replaced with tokens which lose their value beyond the city walls, because they are fiat tokens. They operate on the basis of faith more than a substantial backing. But this coercive element that such a currency necessitates — or, at any rate, did, until forex markets came into being. The coercive element is highlighted more in Plato’s Laws, which, absent the presence of a titled ‘Socrates’, still makes similar proposals, with distinct limits on possession of money according to class — and threats of forfeiture for those who do not conform.

Schumpeter uses this to “claim Plato as the first known sponsor of one of the two fundamental theories of money, just as Aristotle may be claimed as the first known sponsor of the other” (53). Plato, for him, represented a heightened state of thinking that separated money from a store of value. Plato, in theory, advocates for a definition of money in “which the value of money is on principle independent of the stuff it is made of” (53). One cannot fault Schumpeter entirely because he wades into the ‘Plato the fascist’ versus ‘Plato the communist’ debate earlier by admitting that Plato’s ideal city have “features that go far toward defining fascism” (53) whilst rightly pointing out the anachronistic usage of the communist-fascist controversy and keeping in mind what can be recognised more readily as the immensely popular but loose misreading of Plato by Sir Karl Popper. Plato becomes the flagbearer for an admirable economic theory, but is also passingly decried for his seemingly brutish views. That he cannot separate the two as part of a cogent whole, and resolve them into its constituent parts, is perhaps more telling. Schumpeter reads strongly, but he has a tendency to misread just as finely as he reads.

Most telling about Schumpeter’s assessment of Plato’s disciple and spurned successor, Aristotle, is his hope to say what he must “without offense” (54). Invariably, all uses of that turn of the phrase cause offence, and it is always pretence and charade that warrant its unnecessary insertion into conversation, and more frequently in the written word. It is, similarly, harder to fault Schumpeter for this, for he is being a good student of Aristotle, who has been paraphrased and popularly thought (mistakenly so, though) to have said that “I am a friend of Plato, but a better friend of the truth,” or some variation of those words.2 I am sure that Schumpeter was acquainted with that phrase; it is hard to find a student of Plato and Aristotle with such familiarity with the two in the West who does not know of it. And thus, we have digressed. After his show of obeisance, more likely feigned than not, he remarks that he finds Aristotle’s work “decorous, pedestrian, slightly mediocre, and more than slightly pompous common sense” (54). While this statement is a gross mischaracterisation, and the man responsible for teaching Schumpeter Aristotle ought to be remembered as an awfully poor teacher of the Philosopher, it does set the tone for what is to follow.

Chief among Schumpeter’s annoyances with Aristotle — and there are many, for they comprise a sizeable list — is that “he also went hortatory on Virtue and Vice (as we do not)” (54). Clearly, Schumpeter’s annoyance stems from the supposed mess that Aristotle made, subordinating the study of the part to the study of the whole, and also of including ethical concerns as necessarily prior to action and commerce. Although Schumpeter is extremely well read, his stubborn refusal to concede ground to Plato on his moral tactics — the comment about Plato being similar, in many regards, to the fascists, is only in the context of the fascist’s tendency toward certain economic aims — or to others, leads me to believe that like his fellow economists, he revels in Homo Economicus, the overtly rational, self-maximising man who belongs more to the figment of the economists’ imagination than to the corresponding domain of reality.

The corresponding footnote criticises Aristotle for refusing to “assent to the pleasure-and-pain doctrines about behaviour that were gaining ground,” but claims Aristotle secretly harboured a hidden love for utilitarian principles because he committed the “original sin” of having “happiness in the centre of his social philosophy” (54n). Not to stress too large a point, but it seems as though Schumpeter never really paid much attention to Aristotle at all: eudaimonia is qualitatively different from the principle of approbation based on the greatest happiness for the greatest number, or any permutation and combination of that Benthamite principle.3 Later in the text, he comments on Epicurus’ “atomic materialism” band posits “a connecting line that leads from Epicurus to Helvetius and Bentham” (63). He is confused, I think, about Aristotle’s position in this lineage, and although it may seem as they he seeks to expose Aristotle for being one of Bentham’s earliest acolytes, he forgets the footnote he made only a few pages prior. Schumpeter’s allegation, then, is only en passant, but he seeks to mould Aristotle in his own stead — like others have done unto Aristotle — such that Aristotle forms the basis for claiming a lineage that would have otherwise resembled a tree cut from its base.

In Schumpeter’s projection of utilitarian principles onto Aristotle and the tacit advocacy for Homo Economicus, I am reminded of a comment Aristotle makes in the Politics: “People make the lives of the gods in the likeness of their own—as they also make their shapes” (I.2, 1252b26). It is most revelatory, lacking wholly in that “decorous, pedestrian, slightly mediocre, and more than slightly pompous common sense” that Schumpeter accuses Aristotle of peddling (54).

Schumpeter’s original sin is in his understanding the value of money. In praising Plato for recognising the value of money as wholly independent of the medium of exchange it is carried out in, Schumpeter sets up his critique of Aristotle, who is chided for being pedestrian to too ‘metaphysical,’ especially in his view of pricing mechanisms in relation to his standard of commutative justice (58–59). The question, however, is not of the sterility of money itself but the view that Schumpeter adopts, one that could be stretched to most economists today without contortion or distortion and without any suspension of disbelief. Schumpeter’s criticism of Aristotelian money is not wholly without praise — he credits Aristotle with recognising for the first time money as a “medium of exchange,” “measure of value,” and “store of value”: “three of the four functions of money listed in those nineteenth century textbooks” (59–60). Aristotle’s biggest failing for Schumpeter lies in his inability to the think of money as “the Standard of Deferred Payments” (60), which in this case seems to be the function of money that is the first amongst ostensibly equally important characteristics. Why is this important?

Aristotle’s understanding of money is no doubt far more complex that Schumpeter would like his readers to blindly believe. The principle upon which Aristotle constructs his philosophy of money must be examined first in light of the subject being discussed: the polis and the good life. Money for Aristotle is never an end in itself, but only the means to an end. It is, by common agreement, the store of value, the medium of exchange, and the measure of value: that Schumpeter is right about. But what it is most certainly is not is the store of value. Put in more economic terms, one would be led to believe that Aristotle did not think with nuance and complexity about money. This is most emphatically untrue.

“Property,” Aristotle asserts, “is part of the household and the art of acquiring property is part of household management, for it is impossible to live well, or indeed at all, unless the necessary conditions are present” (I.4, 1252b23–25). Property and independence from the tumultuous conditions of commercial life are necessary for the good life — regardless of whether one picks the active or contemplative path — because one ought to be financially independent to devote as much time and resources as possible to one’s pursuits. Property is not an end in itself, but only the means to an end. The same has been said about money, which is not intrinsically different from property. The question of independence is paramount for Aristotle: the truly free man must be free from commercial pressures to be free to do whatever he wants, and with this is the important corollary that only a few can ever achieve that level of comfort required for independent living. Property, by virtue of being part of the household, ought not to be alienated from it: it is the subject of a sort of paternalistic rule by the head of the household.

Aristotle makes an important distinction between the sort of household management that is responsible for the productive use of resources in the household: “there is a second form of the art of getting property … ‘the art of acquisition’” (I.9, 1256b40–41). This ‘art of acquisition’ has as its object a desire for increase wealth in the form of money. Although it seems similar to the art of household management, “in fact it is not identical” (I.9, 1257a2–3). It has as its bedfellow the strange misconception that “there is no limit to wealth and property,” something that even Aristotle cannot wrap his head around (I.9, 1257a1). Having said this, he launches into a discussion of money. In the interests of brevity, we will accept Schumpeter’s tripartite description of Aristotle’s conception of money, and only focus on Aristotle’s supposed repudiation of the fourth: money as the “the Standard of Deferred Payments” (60).

The origins of money can be traced back to the rise of trade outside the bounds of the polis. Barter was difficult because “all the naturally necessary commodities were not easily portable; and people therefore agreed, for the purpose of their exchanges, to give and receive some commodity which itself belonged to the category of useful things and possessed the advantage of being easily handled” (I.9, 1257a35–37). Markings only helped in ensuring that metals commonly used for this exchange did not have to be measured and tested at every step of exchange (I.9, 1257a39–40). Perhaps we ought to remember that the gold standard held court for more than two millennia, and in the grand sweep of history, the rise of currency backed only by faith is a concept yet in its infancy. Roman coins circulated in significant quantities in Muziris and toward the southern tip of India; ‘Senatus Populusque Romanus’ had as much authority in certifying the composition of a blob of precious metal in the Indian Ocean as it did across the English Channel.

But money is not merely a commonly accepted token of exchange: for some, it is their professed goal. The mindless pursuit of money is dangerous and unnatural: it fosters greed, vice, and avarice. Aristotle need only mention the tale of Midas, whose touch turned everything to gold: “A man rich in currency will often be at a loss to procure the necessities of subsistence; and surely it is absurd that a thing should be counted as wealth which a man may possess in abundance, and yet none the less die of starvation” (I.9, 1257b12–15). The mindless acquisition of wealth is not the end of man. In no examination of the good life is the pursuit of wealth the telos of aim or the articulation of any sense of virtue.

By Schumpeter’s own admission, he considers only the view of money and its relation to the polis “mainly in Politics I, 8–11” (57). I do not think Schumpeter lacked in intelligence, but that he refused to deal with the view of the household, money, and household management in light of its moral ends in I.13 of the Politics is stupefying. It is where Aristotle develops his ‘sterility of money’ and the nature of money in more expressed, final terms, where his discussion gives way to conclusions. Moral concerns do not interest Schumpeter, and he brusquely wishes them away as annoyances that ought not to distract the economist hunched over his desk, attempting whatever equilibria he thinks man ought to be subordinated to. But even if he did pay close attention to the minutiae of I.10, which falls comfortably within a view that would befit a horse restricted by blinders, he would see the obvious. It is here that Aristotle’s brilliance shines: he exposes a problem, whilst offering a solution that will be expressed in more complex terms by the schoolmen.

In I.10, Aristotle writes:

“Currency came into existence merely as a means of exchange; usury tries to make it increase. This is the reason why it got its name; for as the offspring resembles its parent, so the interest bred by money is like the principal which breeds it, and it may be called ‘currency the son of currency’. Hence we can understand why, of all modes of acquisition, usury is the most unnatural.” (I.10, 1258b4–8).

If money is all those things that Schumpeter admitted that it is — money as a “medium of exchange,” “measure of value,” and “store of value” (59) — then it is impossible that usury itself be the subject of anything but moral disapprobation. Money lacks an intrinsic sense of value; its only value is inherently derivative. It can be used to measure and store a certain form of value, yes, and this value is the basis of exchange. But it is always referential, never alienated from the use of money. Money can be said to be sterile insofar as it cannot produce offspring. When it is used, it is necessarily expended. Schumpeter classifies this pre-emptively by prescribing to it the character of pedantic common sense, but it must be observed that the very expression ‘common sense’ is an oxymoronic utterance: sometimes that which is most obvious is most easily dismissed as having no validity whatsoever. It is common knowledge that a piece of gold cannot be worth two pieces of gold in the future. In whatever form of reasoning one chooses to apply, 1≠2. But in Schumpeter’s world, it does.

Aristotle understands money far better than most economists. He thinks that money is not an end in itself, and it ought never to be. This is what dissuades him from thinking of money as the “standard for deferred payments” (60). Schumpeter’s disavowal of the moral dimension in economics — the most important dimension, it must be noted — is that there ought to be a use to which money is prescribed, and to which the acquisition of money is held in check with. The moral economy of the household is identified and emphasised with a vitality that still colours the page today:

“It is clear from the previous argument that the business of household management is concerned more with human beings than it is with inanimate property; that it is concerned more with the good condition of human beings than with a good condition of property (which is what we call wealth).” (I.13, 1259b18–20).

The moral dimension is inalienable from the question of property itself, and more specifically of money. How man must comport in relation to financial matters is not an insignificant topic, and if Schumpeter ‘feels’ that Aristotle gave it short shrift, he is most certainly wrong. The subject of household management maintains a prominent place in the very first book of the Politics, and it is foundational to Aristotle’s understanding of the investigation that ensues into the highest sovereign form of association. The concern of the economist is the care and nurture of the Homo Economicus, whilst the care and concern of the political philosopher à la Aristotle is man. It seems that Homo Economicus and man are two different species altogether, and any further examination will show that to hold, even if neither are wholly reflective of the human condition as such in a more empirical sense. At any rate, economic analysis, or the study of whatever it is that Schumpeter exalts over en passant thinking about modes of production and of wealth is more concerned with inanimate property than with human beings as such. It most certainly is not directed toward the “good condition of human beings” but with the “good condition of property.” No economist can deny that they are not constantly troubled by the quality and quantity of productive resources, or, expressed in more mechanistic terms, the ‘stock of human capital’ or other articulations of man as machine. The equation of man as productive resource is a reductionist view of the world and a wholesome view of classical economics.

The Propagation of the Sterile

As we can see above, Schumpeter faulted Aristotle for a supposed casuistry in his work, and for other aspects that ought not to be mentioned again on so prominent and wise a man. The picture Schumpeter paints of the Dark Ages is bright and illuminating, and largely disavows the views adopted by later scholars of the Renaissance. But for the purposes of this essay, focus ought to be directed to perhaps the greatest interpreter of Aristotle, St. Thomas Aquinas, and the tradition of Schoolmen he established, with Aristotle as their headmaster and the Bible as their priest and the world as their curriculum.

The Schoolmen, in Schumpeter’s world, suffered from the same primitivism and erroneous thought that their headmaster was disparaged at length for. Schumpeter writes: “Individual questions, mainly about money and interest, were occasionally dealt with separately. So were political questions. But economics as a whole never was” (79). The sense of disappointment and disapprobation here is far too evident. The pace of Schumpeter’s sentences slows down, and they contract in size, coming almost to a screeching halt. Schumpeter, as we can see with Aristotle, cannot reconcile his admiration for the Schoolmen with what he perceives to be their naivete and backwardness, and as with Aristotle, he charges the Schoolmen with being prototypes of Bentham or of being secret admirers and bricklayers of the beast commonly known as Homo Economicus. Projection in face of internal insecurity about the pedigree of one’s intellectual positions is the sort of faulty teleological thinking that ought to draw ire and earn condemnation, but Schumpeter somewhat unscrupulously faults the headmaster for the correct application of the teleological principle: the headmaster supposedly “gave in, and led followers to give in, to a particular form of the rationalist error, namely the teleological error” (55).

At any rate, Schumpeter makes some key observations about the nature of the late medieval world (or the early Renaissance, depending on which department one waltzes into). The period starting from the thirteenth century — that of Albert the Great (c. 1200–80) and St. Thomas (1225–74) slowly gives way to that of Dante Alighieri (1265–1321), Giotto (c. 1267–1337) and Petrarch (1304–74); the former group are the venerated subject of many a medievalist’s admiration, and the latter some of the founding fathers of the Renaissance, the modern world. But despite the overlap in their years, we are led to believe by most first-rate introductions to the early modern world, perhaps most prominently by Jacob Burckhardt in his The Civilisation of the Renaissance in Italy, the reading of which is a rite of passage for every aspiring Renaissance potentate in the academic world today and for the last century or so, that these two dispositions were violently opposed to each other and bore their relations in only a manner that could be represented as a bitter, acrimonious war of words and morals and aesthetics. It is to Schumpeter’s credit that his study of the medieval world does not suffer from such lacunae, and he recognises fully the richness and vitality of the medieval, which slowly transforms into the modern, not with a jolt and a rupture, but with calm continuity.

After laying out the two ‘cases’ of civilisations — the ‘objective,’ communal civilisation, contrasted with the ‘subjective,’ individualist one (82) — Schumpeter warns his readers of the pitfalls of neatly allocating one to the medieval and the other to the moderns. He writes:

“Is it possible to imagine a fiercer individualist than a knight? Did not the whole trouble that medieval civilization experienced with military and political management (and which largely accounts for its failures) arise precisely from this fact? And is the member of a modern labour union or the mechanized farmer of today really so much more of an individualist than was the medieval member of a craft guild or the medieval peasant? Therefore, the reader should not be shocked to learn that the individualist streak in medieval thought also was much stronger than is commonly supposed.” (83)

This raises significant questions, more so for the non-materialist historian than the materialist sort (associated with a German ‘thinker’ or two, best unnamed). There was always the possibility of neat epochal categorisation, but any astute scholar proficient in the history of the world, the sort that could be seen to move not toward a certain ideological or material end, would recognise the fungibility of categorisation. Most philosophers find it hard enough to ply their trade without historical scepticism entering the foray, and here it is only sufficient to comment that although the serf and the manor, the mainstays of the medieval world, reflect one sort of organising principle, the Schoolmen’s philosophy and theology reflect another sort. It is perhaps time for a suitable reminder: St. Thomas, who found brutal condemnation in the years immediately following his death was canonised within half a century of it, named a Doctor of the Church in 1567, and by 1917, his position in Church doctrine and canon law was elusive and exclusive.

That being said, it must still be emphasised that the medievals, particularly the Schoolmen, are still ‘relevant’ in their style, grace, and expression, and there is much to admire in their work. Schumpeter keeps the vitality of St. Thomas alive, but his revolution does not happen there: it occurs at the margins, with thinkers who fail to show in the blinding brilliance of St. Thomas. It is in this context that Schumpeter writes the following:

“In what may be described as the applied economics of the scholastic doctors, the pivotal concept was the same Public Good that also dominated their economic sociology. This Public Good was conceived, in a distinctly utilitarian spirit, with reference to the satisfaction of the economic wants of individuals as discerned by the observer’s reason or ratio recta (see, below, next section)—and is therefore, barring technique, exactly the same thing as the welfare concept of modern Welfare Economics, Professor Pigou’s for instance. The most important link between the latter and scholastic welfare economics is the welfare economics of the Italian economists of the eighteenth century.” (93)

This is a most curious comment to be made. The medieval reputation for the harsh darkness of ignorance is replaced with another, more scalding one: that of being proto-Benthamites. Such a reputation was unfairly and unfoundedly attached onto Edmund Burke, whose philosophical star diminished in brightness for a considerable period precisely due to this sordid and bigoted mischaracterisation. In the same vein, one ought to be aghast that between what one can only assume to be Schumpeter’s lusting for a utilitarian history and an otherwise overworked imagination, the ills of 19th century intellectual fads and 20th century economic philosophes — every bit as radical as those responsible for the travails of 1789 — are carried back to the venerable remains of the past. What is this concept of ‘welfare’, of the summum bonum, that is prescribed a utilitarian tinge? Schumpeter’s projection of some modified form of proto-Epicureanism and proto-utilitarianism onto Aristotle was rather without basis, and his projection here is implausible and possibly wholly unfair. But the assertion that those honourable Schoolmen had something to do with ‘welfare economics’ as conventionally understood — those who think that the summum bonum ought to be expressed in mathematical terms, with selection of random ‘facts’ as results of whatever methodological fad they subscribe to, resulting in what would have been described only as a pseudoscience — is downright implausible. Although they had, as we shall accept, an individualistic streak in their thought, the Schoolmen did not suffer from moral depravity, and Schumpeter can never address the major question at hand: why did they always subordinate their ‘economic’ thought to matters of theological, philosophical, and even political concerns? It was only because they understood that the whole is always superior to, and prior to, the parts: this is what their headmaster had taught them, noting rather wryly that “the whole is necessarily prior to the part” (I.2, 1253a20). If the household — the basic unit of organisation in the polis — necessarily belongs to the polis, then the art of its management ought to, as well. The question of economics is always that of political economics, however oxymoronic that may be, and the quantitative approaches that classical economics take eschew that approach, advocating for the tacit erasure of the state in favour of a state that only ought to look at being the guarantor for punishments in the wake of broken contracts and as the registrar of property and transactions. The justification for the minimal state, the ‘amoral’ science of economics — if such a thing could ever be said to exist with a degree of certainty and without having wool pulled over one’s eyes — is put rather succinctly by the economic historian Raymond de Roover, in his survey of scholastic economics: “Trade has no soul and the individual did not count: why should the mercantilists be disturbed by moral issues?”[ Raymond de Roover, ‘Scholastic Economics: Survival and Lasting Influence from the Sixteenth Century to Adam Smith’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 69, no. 2 (May 1955): 161–90, at 180.]

The same economic historian makes an interesting remark that dictates in no small part Schumpeter’s approach to the scholastics: “The great weakness of scholastic economics was the usury doctrine.”4 The question of what to do when credit for business activity was declared illicit — contrasted with loans for gratuitous personal consumption beyond one’s means — is a touchy subject, as it was for Plato in the Laws: he forbade the lending of money beyond that which one could not afford to lose, whilst Aristotle could not conceive of a sterile object being able to reproduce and propagate itself. But it cannot be denied that there was always a need for credit, especially in the daily transactions of business activity. Schumpeter’s solution to this dilemma is coloured with a historicist tinge, and it is this that we ought to examine and perhaps challenge with some gusto. There are two homologous claims that Schumpeter makes:

“The reader will observe that I do not assign to the recovery of Aristotle’s writings the role of chief cause of thirteenth-century developments. Such developments are never induced solely by an influence from the outside. Aristotle came in, as a powerful ally, to help and to provide implements. … The economic process was evolving patterns of life that called for legal forms, especially for a system of contracts, of the type that Roman jurists had worked out. … The Roman law came in usefully, not because it brought something that was foreign to the spirit and needs of the age … but precisely because it presented, ready made, what without it would have had to be produced laboriously.” (84–85)

This is a garden variety historicist claim, with nothing spectacular about it. More puzzling is his words in the same chapter, which seem to show that the ‘decline’ of industry never really happened. For example, he remarks:

“The society of feudal times cannot be described in terms of knights and peasants any more than the society of capitalist times can be described in terms of capitalists and proletarians. Roman industry, commerce, and finance had not been destroyed everywhere. Even where they had been destroyed or where they had never existed, they—and consequently classes of bourgeois character—had developed or developed again before St. Thomas’ day.” (71)

It can be safely assumed that this is a claim rather distinct from the claim advanced on pp. 84–85, which is quoted above. Here, he seeks to let loose on those who seek to claim the medieval era as some sort of ‘dark age,’ and although he does not direct his animus toward the individual responsible for said characterisation, Petrarch, he does paint a vivid picture. Elsewhere, he says that “by the end of the fifteenth century most of the phenomena that we are in the habit of associating with that vague word Capitalism had put in their appearance, including big business, stock and commodity speculation, and ‘high finance’” (75). Any student of Florentine economic history will instantly balk at this claim, and he must for it puts the development of the complex economic forms that governed Italian banking and trade at least two hundred years later than its first important occurrence.5 Medieval banking, trade, and business are far more complex than Schumpeter was willing to admit, and while de Roover rightly recognises the Achilles’ heel of the schoolmen as their casuistry in regards to usury, Schumpeter speaks of it in more general and sympathetic terms. But the historicist tinge never goes: it assumes that profitable deployments of capitalism developed significantly in more recent years, somewhere between the 12th and the 15th century, depending on which page you happen to open on a particularly day, and that pushed the schoolmen to write apologias for usurious loans without making either the all-too-important distinction between licit and illicit contracts, or otherwise some sleight of hand that would permit business credit. De Roover, armed with brevity, remarked after noting that whilst the original ethical reasoning of the schoolmen was referred to as casuistry, their ingenious workarounds acquired for them a poor reputation, where they were rightfully accused of being faithfully only to the letter and not the teachings of their philosophical-theological enterprise. He scathingly asked: “Is it then surprising that casuistry acquired such a bad connotation and is today synonymous with sophistry and mental reservation?”6

At any rate, let us consider Schumpeter’s representation of the late scholastic argument for interest-bearing loans in broad strokes before looking at his examination of permissive usury in St. Thomas. Schumpeter characterises the general thrust of the argument that business credit is not usurious as follows: “… deviation of interest from zero is a problem the solution of which can only be found by analysis of the particular circumstances that account for the emergence of a positive rate of interest. Such analysis reveals that the fundamental factor that raises interest above zero is the prevalence of business profit …” (101). This is a startling claim for a historicist like Schumpeter to make: if the thirteenth century or thereabouts had as its marker the development of certain historical facets that would enable certain lines of thought to become more relevant, and consequently bring to the fore the work of the Roman jurists and Aristotle as a handy crutch, what made it unique? Here, Schumpeter seems to be arguing that the scholastics only came up with the distinction between interest-bearing loans and usurious loans because of the “prevalence of business profit,” a most curious and ahistorical claim to make. If business were truly unprofitable, how would any society sustain itself? If the state exchequer and the treasury spent all there gold on fiscal stimuli of various sorts because daily activities were sorely unprofitable, how did medieval society survive? Business profit is a wholly insufficient explanation for the comprehension of scholastic approaches to business. What could be plausible — but Schumpeter happens to rule that out in passing — is the development of business activity on such a scale that everywhere one looked, one would see transactions happening. The world would become a marketplace. But that, too, would be grossly inaccurate: the medieval world, while qualitatively different, still maintained important aspects of business activity that certain historians with an eye toward ‘progress’ would like to believe. Schumpeter’s analysis is rather susceptible to the chicken-and-egg problem: we have evidence that the chicken, business profits, came first, and that the defence of usury, the egg, came later — but the issue is that business profits were always there, and the defence of usury ought to have no relation whatsoever, except in poor historical terms, with the corresponding rise in business activity. The world that Aquinas entered into — the world of thirteenth century Italy — was rich and vibrant, full of bankers and a host of businessmen who plied their trade across Europe. The same can be said for the later scholastics, who knew of and countenanced business itself whilst pushing for ethical action within it.

St. Thomas looks at usury with significant nuance, nuance that is largely lost in Schumpeter’s retelling. We are primarily concerned with the views in the Summa Theologica, particularly II–II qq. 77–78.7 The account, however, that has been provided in 77, art. 4, shows no deviation from the account Aquinas provides in his commentary on the Politics, which is why discussion of the latter text is omitted here.8 The order of business shall be as follows: we ought to examine the veracity of Schumpeter’s claim that the Scholastics, “undoubtedly held the opinion expressed by St. Thomas, namely, that there is ‘something base’ about commerce in itself” (88), and then examine St. Thomas’ views on interest, particularly in light of q. 77, art. 4.

Did St. Thomas harbour some animus toward the commercial world as a whole, or was it directed toward certain acts that warranted interest and condemnation from a theological and philosophical standpoint? Schumpeter picks up on a particular turn of phrase, but lands up losing the forest in the trees. The phrase in question is in ST II–II, Q77, A4. But the entire question, directed as it may be to instances of cheating and fraudulent exchange of various sorts, tells another story. It is wholly sympathetic to the businessman, whilst stringently advocating for the rights of the consumer that can be applied to any number of transactional situations. Take, for example, the third article of the same question. The reply to the second objection is as follows:

“There is no need to publish beforehand by the public crier9 the defects of the goods one is offering for sale, because if he were to begin by announcing its defects, the bidders would be frightened to buy, through ignorance of other qualities that might render the thing good and serviceable. Such defect ought to be stated to each individual that offers to buy: and then he will be able to compare the various points one with the other, the good with the bad: for nothing prevents that which is defective in one respect being useful in many others.” (ST II–II, Q77, A3, ad 2).

One might even say that in this instance, St. Thomas’ sympathies lie not with the buyer, but with the seller. The disclosure of defects in public would reduce the price being offered for it, but if those defects are fully disclosed to potential buyers individually before the transaction is commenced, then the seller has performed his obligations. Anyone who has had the distinct misfortune of being stuck in front of the television — and this is true of the United States more than any other nation — will be bombarded with an unending barrage of commercials, of which those containing anything to do with pharmaceuticals will have at their close a voice speaking at the limit of human comprehension of adverse side effects, ‘defects’. In other countries, risks associated with certain medical treatments are revealed not through the ‘public crier’ of the television, but through doctors. That is a matter of convention, more than anything else, but only serves to elucidate Aquinas’ emphasis on the communication of defects. The intent here, clearly, is to ensure that the seller gets the just price for his goods as much as the buyer receives that which he paid the just price for. Earlier in the response, it is stated that “if the defect be manifest, for instance if a horse have but one eye … he is not bound to state the defect of the goods” (ST II–II, Q77, A3, resp.) Obvious defects — a unicorn without a horn, for example, ought not to be sold as a unicorn; neither must the buyer be so naïve that he not comprehend the difference between a unicorn and another equine creature — ought to not be stated. This is not the attitude of someone who is opposed with every sinew to trade and to the commercial world. St. Thomas understands the commercial world, and though he does not countenance some of its practices, he does not reproach it in its entirety. He leaves to the domain of ‘common sense’ that which ought to be commonly known, and he does not pedantically dictate the minutiae of market exchange mechanisms, because he recognises the great flexibility and changes that can take place in the form of those norms across space and time.

The gist of the following article — Q77, A4 — follows in a similar vein. The response is worth is put in economic terms by Schumpeter accurately:

“[For St. Thomas,] commercial gain might be justified (a) by the necessity of making one’s living; or (b) by a wish to acquire means for charitable purposes; or (c) by a wish to serve publicam utilitatem, provided that the lucre be moderate and can be considered as a reward of work (stipendium laboris); or (d) by an improvement of the thing traded; or (e) by intertemporal or interlocal differences in its value; or (f) by risk (propter periculum).” (87)

But this is where Schumpeter and I must take separate paths. Schumpeter chides St. Thomas for his simple understanding and devaluation of economics, for he does not read the entirety of the fourth article, which contains this gem:

“… gain[,] which is the end of trading … does not, in itself, connote anything sinful or contrary to virtue: wherefore nothing prevents gain from being directed to some necessary or even virtuous end.” (ST II–II, Q77, A4, resp.)

St. Thomas’ exhortation is not only to do the right thing, and act morally in going about one’s commercial life, but also in how one uses the fruits of commercial life. A life of decadence ought not to be the aim of profit-making. Even the exhortations themselves show that there is more than ample room for virtue and justice in the commercial world, and it is contingent upon individual souls to act in the manner most conducive to virtue. St. Thomas stresses upon the individual and his agency, for in his remarks on usury he readily admits that the law ought to correspond to the imperfection of this world:

“Humans leave certain things unpunished, on account of the condition of those who are imperfect, and who would be deprived of many advantages, if all sins were strictly forbidden and punishments appointed for them. Wherefore human law has permitted usury, not that it looks upon usury as harmonising with justice, but lest the advantage of the many should be hindered.” (ST II–II, Q78, A1, ad. 3).

This is a suitable segue into the world of St. Thomas’ views on usury. As we have seen before, there were a variety of conditions under which St. Thomas was ready to permit business activity. I would dare say that most of those conditions still hold today, and that we ought to think more carefully about commercial decisions that require some change to be forced to fit in these criteria. But, I digress. St. Thomas’ views on usury are complex. They are not the simple-minded actions of a “dumb ox,” as G.K. Chesterton fondly called Aquinas. Take, for example, this line of argument:

“A lender may without sin enter an agreement with the borrower for compensation for the loss he incurs of something he ought to have, for this is not to sell the use of money but to avoid a loss. It may also happen that the borrower avoids a greater loss than the lender incurs, wherefore the borrower may repay the lender with what he has gained. But the lender cannot enter an agreement for compensation, through the fact that he makes no profit out of his money: because he must not sell that which he has not yet and may be prevented in many ways from having.” (ST II–II, Q78, A2, ad. 1).

Does this, read strictly, remove one from considering the time value of money? Take, for instance, this ‘thought experiment’: I lent 10 ingots of gold today to a friend, who was to use that as working capital for his business, to be repaid in five years’ time, and that 10 ingots of gold today would buy a ton of wheat. Due to inflation and other external factors, I could only buy three-fourths of a ton in five years’ time. Is this a just transaction? The lender is worse off than the buyer. It fails Aquinas’ test of just price. The price that is being paid for an advance of business capital in some way, shape, or form is being repaid in a de facto lower sum, although it is de jure the same. Money borrowed must be paid back in equivalent terms, even if it is construed in relation to its purchasing power, which is the standard of exchange and store of value definition Aquinas derives from Aristotle. This provides a limited set of actions that one may use in order to recompense the lender, if only by the demands of justice: one ought to repay a loan in full. The question of usury begetting sin is only when it is used to advance personal wants and mores. Ad. 5 of the same response includes a preliminary sketch on the understanding of unlimited liability in corporate structures, showing that Aquinas thought and articulated moral and theological viewpoints on such matters as well, although the titles of his questions were more often than not wholly inadequate in encapsulating the vast subjects they dealt with.

“It is lawful,” St. Thomas reminds future students, “to make use of another’s sin for a good end, since even God uses all sin for some good” (ST II–II, Q78, A4, resp.). This is the principle he applies to usury. The lawfulness of taking a loan with corresponding interest payable upon the principal in kind or in cash is contingent upon the ends to which it is applied. In a perfect world, no one would charge interest, and one ought not to borrow if one knew that paying back such a loan would be impossible to repay. The question of reciprocation always arises: the loan is like Mauss’ Gift. But the question of the ends and title has, in a quintessentially Thomist fashion, a neat, succinct, and tidy resolution: goods purchased with the help of an interest-bearing loan are “due to the person who acquired them not by reason of the usurious money as instrumental cause, but on account of his own industry as principal cause” (ST II–II, Q78, A3, ad. 3).

This is just scratching the surface. Even this short excursus of St. Thomas’ thought is wholly insufficient for any number of reasons, save for one: to show that St. Thomas thought carefully about the commercial world, that he was careful to take man as he is, in all his imperfection. Perhaps Schumpeter — and other economists — ought to remember this: Gratia non tollit naturam, sed perficit.

Concluding Remarks

I have only touched upon a few of Schumpeter’s ideas and encapsulations, and only briefly. The same can be said about my treatment of all the philosophers discussed here, from Plato to Aristotle to St. Thomas. But there is only one point of order that I ought to emphasise on, if only because it seems as though it is a lost cause — and that is the case of the ‘moral economy.’

Schumpeter observes — rightly, this time round: “Exactly like the scholastics, the philosophers of natural law aimed at a comprehensive social science — a comprehensive theory of society in all its aspects and activities — in which economics was neither a very important nor an independent element” (113). The scholastics and natural law theorists10 saw the whole, and face criticism for not giving importance to a part that a certain cabal thinks to be of superior merit. Unfortunately, the materialist world of the economist is not the world in which man lives. As I have expressed before, the atomist, materialist ‘thing’ in motion is not man: it is only a brute.11 It lacks a soul, the non-material element which makes man yearn for beauty, lust for travel, and aspire to knowledge, honour, and greatness. The Homo Economicus, unencumbered by moral constraints or the weight of a conscience, is unable to perceive the subtlety and sublimity of this world, and seeks refuge by using his pursuit of wealth to hide his deep insecurities and inner restlessness. That is precisely what Aristotle and St. Thomas warns us against: money is no good, and the industry expended in acquiring it of no consequence whatsoever, unless it is oriented to the ‘good life’ (and not the hedonist life) broadly understood. It is a means to an end, not an end in itself. The reason why economics, I think, is such a small (but by no means insignificant) part of the work of the schoolmen and the natural law theorists is that they see a much larger world.

I started my academic journey as a student of the history of art; I studied the Renaissance in Florence with admiration, tenderness, and love. I saw a large, interconnected world. Yet, remarkably little of that world was the world of business.12 The good life is the one that is worth living, but no economist will ever tell you why, or what it consists of. For too long, the study of economics has been alienated from the household. The focus has been on ‘productivity,’ not on honour and virtue. We must not make the world anew, but we must seek to understand it in terms more suited to the essence of man and his existence. I have expressed before a desire to think of property in different terms: when conceived off as a series of duties and obligations instead of a persona ficta is more effective in ensuring generosity, for then one perceives a certain moral obligation to do so. That is only one example. And it is precisely that rich understanding that classical economics seems to negate, regardless of whether said economist is a ‘socialist’ like Schumpeter, or Marx, whose dictatorship of the proletariat is another sort of unmitigated disaster, or Hayek, who denies the potential for politics itself in his ‘spontaneous order’.13 No economist ought to escape criticism for looking at the human world through a horribly brutish lens, characterised by a bellum omnium contra omnes.

- Joseph Alois Schumpeter, History of Economic Analysis, ed. Elizabeth Boody Schumpeter (London: Routledge, 2006). ↩

- For a brief look at the history of that turn of phrase, look here: Henry Guerlac, ‘Amicus Plato and Other Friends’, Journal of the History of Ideas 39, no. 4 (1978): 627–33, https://doi.org/10.2307/2709446. ↩

- I examined the error of Adam Smith in thinking that happiness — different from eudaimonia — ought to be the telos of life in another brief essay. The entry includes an account of the difference between ‘happiness’ and eudaimonia in Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics: https://journeys.dartmouth.edu/otemporaomores/2020/07/04/adam-smiths-hidden-debt-to-thomas-hobbes/ ↩

- Ibid, 173. ↩

- For a good analysis, see Richard A. Goldthwaite, The Economy of Renaissance Florence (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009). ↩

- De Roover, ‘Scholastic Economics’, 173. ↩

- Quotations from the Summa are from the standard translation by the Fathers of the English Dominican Province. ↩

- See the comments Aquinas makes on p. 60 and p. 64 of this edition, which are alternatively at 1.8.10 and 1.9.3. Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on Aristotle’s Politics, trans. Richard J. Regan (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Company, 2007). ↩

- The question of the public crier only comes as part and parcel of an example borrowed from Cicero’s On Duties, not on the actual act of hiring a public crier. This is, perhaps, Aquinas’ sense of humour, but here we are only concerned with his philosophy. ↩

- This group ought not to be tainted by Hobbes and Locke and their students, for their ‘natural law’ is not the ius naturale of the Roman and Scholastics tradition or of Grotius’, for that matter. ↩

- https://journeys.dartmouth.edu/otemporaomores/2020/07/08/self-interest-as-a-moral-maxim/ ↩

- https://journeys.dartmouth.edu/otemporaomores/2020/05/20/the-art-historian-as-political-philosopher/ ↩

- https://journeys.dartmouth.edu/otemporaomores/2020/07/01/the-deterministic-conceit/ ↩