Maternal Health in Nicaragua: History & Implications of Nicaraguan Reproductive Rights

Women’s reproductive rights, specifically access to abortion, is always a contentious topic. In most countries one will find reasonably sized populations considered both “pro-life” and “pro-choice” which respectively oppose and support a woman’s right to end her pregnancy. However, in most cases, even the staunchest supporters of a ban on abortion are willing to make exceptions in certain cases. More specifically, many pro-life politicians and supporters believe that abortion should be allowed in cases where a pregnancy threatens the life of the prospective mother. A large contingent also believes in abortion rights for victims of rape and / or incest. These seem like reasonable exceptions to many people, and so are typically written into the laws of countries that oppose abortion on religious or moral grounds. Nicaragua, however, is unique in that it maintains a complete ban on abortion in all cases – even in the case of pregnancies that pose serious risks to the life of the pregnant woman (12).

How did we get here?

Abortion rights in Nicaragua have a long and complicated history. Under the Somoza regime, women were denied access to abortion as well as any prenatal care or treatment that might accidentally lead to a miscarriage. As a result, botched illegal abortions became the leading cause of maternal mortality, and women suffering from the complications of these abortions were allowed to die without treatment so that doctors could avoid liability (3). However, as the Sandinistas moved towards victory, it appeared that these trends might improve. Data collected on the sheer number of deaths from illegal abortions and a desire to mobilize more women led the Sandinistas to unveil potential legislature that seemed to indicate a more progressive position on women’s rights (7). New laws protecting against domestic violence and rape were being considered, creating the potential for a new era in which spousal rape and abuse were considered crimes rather than “outside the jurisdiction of the courts” (3).

Then, in order to secure the support of the Catholic church, support for women’s reproductive rights was rolled back following the Sandinista victory. Feminists had a slightly larger voice in society, and gender equality was officially codified into law in the new constitution in 1979, marking key advances in women’s rights. There was also legal action to establish broad sexual education (3). Access to abortion and birth control remained taboo, to the point that a proposal to include a woman’s right to decide how many children she wants and when she wishes to have them was rejected by the constitution’s authors (3). There was, however, some relaxation of the strict regulations on abortion, including the formation of hospital committees to discuss the abortion ban and the establishment of one European clinic where first-trimester abortions were performed legally (18).

The result of this was a society that had improved gender equality by some legal measures, but remained heavily prejudiced against women’s reproductive rights and the rights of wives to defend themselves against physical and sexual violence. Some advances were made, while some parts of the law lagged behind. Later, many of these gains would be even further reversed under the UNO government of Violeta Chamorro. Her positions opposing abortion, birth control, comprehensive sexual education, and divorce fell in line with the beliefs of the Catholic Church and a strict pro-family administration. The abortion committees at hospitals were shut down, sex education was returned to abstinence-only, and attempts at increasing access to abortion were halted (18). This brought the reproductive rights movement back to its initial starting point, a place where it remains today.

What is today’s state of affairs?

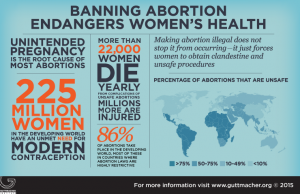

Today, women’s rights are improving in Nicaragua, with greater political involvement and better support for the feminist movement. However, the Sandinista administration of Daniel Ortega has left the total ban on abortion in place. As of November 18, 2006, abortion has been declared completely illegal, no matter the circumstances. Unsafe illegal abortions remain a leading cause of death, and laws criminalizing the provision of medical care that leads to an accidental miscarriage continue to restrict the prenatal care that doctors can provide (12, 13).

This has widespread implications for women’s health in Nicaragua, especially given the lack of access to birth control that remains an issue for young Nicaraguan women. In Nicaraguan culture, young women are not meant to admit that they are sexually active, which means that they often feel they cannot seek out birth control. There is also a strong machismo cultural element encouraging premarital sex and even the fathering of children by young Nicaraguan men (18). These cultural factors combine to produce a great deal of unwanted and, if the pregnant girl is young enough, potentially dangerous pregnancies. This coupled with lack of access to safe, legal abortion will continue to result in healthy young women dying from unsafe procedures over time unless at least one of these factors begins to change.