El Mestizo y Los Mestizaje

When thinking about the term “mestizo” and the “mestizaje”, one might believe that they mean nothing more than the mixing of two races. Up until the 20th century, the meaning of the term was meant to be derogatory towards people of mixed race, especially when the Spanish began to interbreed with the native and indigenous people of Latin America. The term has since carried a more positive connotation, seen as a sense of pride for one’s cultural background and heritage. By the year 1910, nearly half of the population in Mexico was considered “mestizo”, stemming from the indigenous and Spanish populations. Even though they were part Spanish, there was still a rift between the full-blood, upper class Spaniards, and the working class mestizaje and indigenous people. As this divide continued to grow, tensions also began to rise between the upper class and lower class societies. This set the stage for a revolution and change not only politically, but within all aspects of life in Mexico.

Throughout the 20th century, the “mestizaje” became a leitmotif for many artists, stemming from muralists to writers alike. Artists used the image of the mestizo to capture the essence of the revolution, as well as depicting the realities of the war in Mexico. Muralist Diego Rivera and novelist Mariano Azuela are two examples of how artists were able to use this image in their works, portraying the mestizaje fighting the government in attempts to yield power from the upper class and give it back to the common people of Mexico. In Rivera’s mural The Liberation of the Peon and in Azuela’s novel The Underdogs, both artists portray the mestizaje as a heroic figure fighting for the common man against the oppression and abuses of the Mexican government and the bourgeoisie.

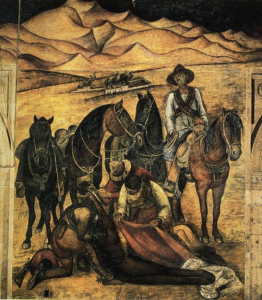

In The Liberation of the Peon, Rivera illustrates life of the men fighting during the Mexican Revolution. In the mural, a group of mestizo-looking men are seen gathered around another man lying on the ground. With his hands tied to a stake in the ground, the man lies naked, and seems to have been abused from the scars that stripe his back. Upon first glance, he looks nothing more than a lifeless body in need of rescuing. Rivera seems to be expressing the reason behind the start of the Mexican Revolution, which is the oppression and abuse of the working class by the upper class. The tying of the hands presents the thought that the government and wealthy are supposed to have total control over the workers, while the scars on the back represent the punishment and abuse of powers that they use in order subjugate the workers to a life of indentured servitude. Fortunately for the man, a small group of people have come to free him from being bound and take care of his wounded body. By helping the man, Rivera suggests that these mestizo men are heroic and noble people, capable of helping to save society from the corruption throughout the country. Rivera not only wanted to show that these mestizo people were valiant based upon their actions in aiding the helpless man, but also wanted to depict these men as true fighters whom resembled the mestizo revolutionaries.

Although Rivera’s intent with the mural was to illustrate the freedom of the woking class from the maltreatment of the upper class, he was certain to make sure that the people, who were liberating the peasants and the common man, were the revolutionary mestizaje. Rivera outfitted

the men in clothing and equipment that typified what revolutionaries wore during the war. All of the men are wearing sombreros, with guns around their waists, as well as bandoliers of ammunition around their chests. Additionally, another detail that Rivera includes in the mural, is the burning of the pueblo that sits a distance away from the men in the background. Historically, revolutionaries would travel to pueblos across in search of supplies and aid in order to fight the Federales. Rivera understood that, although these men were revered as valiant people fighting for a greater purpose, they still had their own flaws which hindered them from being perfect. Even though Rivera acknowledges the reckless burning of the pueblo resembles the dark and destructive side of the mestizaje, he undoubtedly wanted to make it apparent that the mestizaje were helping to change the country from its corrupt and oppressive ways.

Above all the men in the mural, there is one who sits on a horse while the others help the abused man. This man is seemingly portrayed as the leader of the group, sitting high above the others and looking on as if he had just given them orders. He is reminiscent of the character Demetrio Macías in Mariano Azuela’s novel, The Underdogs. Like the man in Rivera’s mural, Demetrio was portrayed as the leader of his rebel group of fighters, who joined the revolution to fight against the Federales. Prior to joining the fight, Azuela describes Demetrio as a farmer with a family, illustrating him as, “tall and well built, with a sanguine face and beardless chin; he wore shirt and trousers of white cloth, a broad Mexican hat and leather sandals” (Azuela 4). Azuela writes of Demetrio, just as Rivera painted the men in the mural, wearing the same typical clothing as that of the Mexican common folk. By expressing Demetrio in this manner, Azuela is able to demonstrate how the most heroic characters during the revolution were common workers and peasants.

In addition, Azuela, much like Rivera, also spotlights the dark side of the mestizo revolutionaries. For example, after visiting the house of Don Mónico, Demetrio orders Luis Cervantes to burn the house down. After Luis carried out the order, Azuela chronicles, “a couple of hours later the small town plaza was full of black smoke, and the enormous flames lapped up from Don Mónico’s house” (Azuela 90). Consistent with the Rivera’s mural, Azuela shows how theses heroic figures also carry their own demons, which further humanize, but do not take away from the courageous actions taken by these men in fighting the Federales. Understanding the flaws of these heroic characters connected these artists views of the mestizaje and how they were viewed during the revolution.

The Mexican Revolution was certainly a time when the mestizaje began their rise in the public spotlight. For years, the mestizo people had been thought of as the “lower class” of Mexican society, being neglected and often maltreated by the bourgeoisie. Artists like Diego Rivera and Mariano Azuela began to use the mestizaje and the revolution as a means of producing works that connected with working class people of Mexico, as well as portraying what the war was like. While also addressing some of the flaws of these men carried, both Rivera and Azuela were able to display the mestizaje as heroes of the revolution, who fought for the people of Mexico against the upper class. The similarities of both The Underdogs and The Liberation of the Peon provide insight as to how the mestizaje was portrayed by artists and the rest of society during the Mexican Revolution.