Who Authorizes Art?

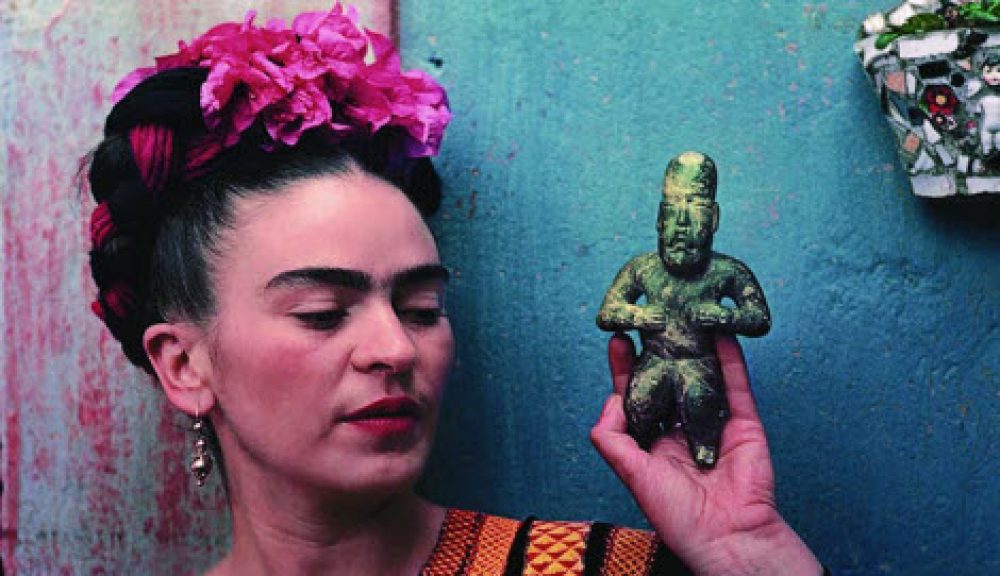

To understand a work of art, one must be able to understand the artist themselves and be able to comprehend the thought process by which their art is influenced. Often an artists’ ideas and works can be conflicting of societal ideologies or social norms, which can be controversial and upset groups of people. This can certainly put a damper on an artist’s career, as they rely on commissions from private and public sources in order to make a living. While some artists tend to have different styles and means of creating art, others are forced to conform to the styles that are popular to gain commissions and stay afloat in this uncertain career path. Art, though, is not confined to a specific style or color scheme, but rather is a form of expression in which anyone can convey a message that they feel is important. Frida Kahlo understood this better than most artists of her time, painting controversial art that would define her, not only as an artist, but also a person.

Unlike most artists during her time, Frida Kahlo was lucky enough to not have to rely on commissions and the selling of her artwork to make a living. Kahlo had the support of her world-renowned husband, Diego Rivera, to make a living for her. In fact, for the first few months of marriage to Rivera, Kahlo did not paint at all. It would be a sense of loneliness and isolation that she renewed her talent for painting as a means of filling the void left by Rivera during his work days. Initially, Kahlo began painting self portraits, as well as portraits of other people, giving them as gifts to those that she felt gratitude toward. For example, in 1930, Kahlo and Rivera traveled to San Francisco where he had received commissions for work. They were only able to enter the United States thanks to the help of Albert Bender, an international art collector.

To show her appreciation for the tireless help of Bender to get them to the United States, Frida painted a wedding portrait, entitled Frida and Diego. She would go on to do this for others, such as her personal physician, Dr. Leo Eloesser, who would help her get through many of her life crises, as well as physically examine her health. For Frida, though, her artwork was not about how much she got paid or the commissions she received. Rather, Frida was more worried about how her art work reflected herself above all else.

In all aspects of her life, Frida was not afraid to stand out and separate herself from others around her. Her artwork was no exception to this quality, as her works were often deemed as graphic and untraditional at the time. While much of the Mexican art that was produced during the early decades of the 1900’s incorporated either political or nationalistic themes, most of Frida’s art portrayed real life tragedies, as well as pain that she had suffered or was feeling at the time. For example, Frida’s painting My Birth (1932) depicts a woman lying on a bed with a sheet laid over her head, as she gives birth to a baby Frida. Below the baby, whose head is protruding from between the woman’s legs with her eyes closed, there is a pool of blood staining the sheets of bed. Just above the bed’s headboard, a picture of the “Virgin of Sorrow” hangs, sadly watching over the gory scene and unable to help the woman. This picture, while meant to represent the stark contrast between life and death, was “a startling image for Western audiences since childbirth has not been addressed, if at all, so frankly in Christian iconography” (Motian-Meadows 1).

For many viewers during that time, the image of a dead woman giving birth to a baby with a puddle of blood on the sheets was shocking and ghastly. Other Mexican artists did not portray pain and suffering in this realistic style that would define much of Kahlo’s art. Although Kahlo certainly pushed the boundaries of what was socially acceptable when it came to her artwork, what made her art stand out more than others, was her ability to make her pieces relate to the struggles and sufferings faced by much of her audience.

Throughout most of her life, Frida struggled to deal with pain both physically and emotionally. Physically, her body had been severely damaged and scarred, due to a horrific bus accident, as well as contracting polio and gangrene which would result in the loss of her leg. All of her physical pain would take a toll on her emotionally, adding on to her tumultuous marriage to Diego Rivera. For Frida, painting would be a means of both portraying her pain and creating a “creature she invented to help her withstand life’s blows” (Lindauer 4). As she began to rise throughout the art world and gain more notoriety, Frida’s audience, especially women and underrepresented groups of people, began to relate to the trials and tribulations faced by Kahlo throughout her lifetime. Pieces, such as The Broken Column (1944), serve as an inspiration for viewers who are struggling in parts of their lives. In the self portrait, Kahlo paints herself with support belts bracing her, exposing most of her upper body, which has been split down the middle. A tattered column supports her upright posture in place of a normal backbone, suggesting the “bend but don’t break” attitude that someone, like her, needed to have to succeed in an industry dominated by men. Included are also nails piercing her body everywhere, and

although there seem to be tears that are running down her cheeks to show that she is in pain, she still has a straight face to signify that she is determined and unrelenting. Throughout all of her paintings, Frida understood that the portrayal of her pain went far beyond what she felt, commenting, “they have a message of pain in them, but I think they’ll interest a few people. They’re not revolutionary, so why do I keep on believing they’re combative?” Even though she was only painting what she felt at the time, Frida still understood that her art had significant influence and power over her audience. Works of art like The Broken Column exemplify how Kahlo’s pain and struggles throughout her life was relatable to a wide variety of people during that time, which would propel her to become a cult-like figure after her death.

For Kahlo, painting was not a job or profession in which she needed to utilize her talents to make money. Rather, Kahlo’s art was meant to express her own thoughts and feelings through self reflection, such as her most famous piece, The Two Fridas (1939). This painting serves yet another shining example of the dark and unconventional style by

which would create such a masterpiece. It would be works like The Two Fridas, that would help to shape Kahlo’s image as both an artist and inspiration for numerous social change movements around the world. Frida was not concerned with her art or what others thought of her art, stating, “The only thing I know is that I paint because I need to, and I paint whatever passes through my head without any other consideration” (Kahlo 1). Kahlo did not need money or commissions to paint, but found that her own reality gave her enough motivation to create artwork that would cause both controversy and sweeping change for generations to come.