Introduction

Native American Assimilation and the Definition of “Citizen”

The period of Native American assimilation began roughly in 1880, with the start of the boarding school movement, and although the last boarding school was not closed until the 1960s, this era arguably ended when Native peoples were granted citizenship within the United States in 1924 with the Indian Citizenship Act. During this time period, Indian lives underwent some incredible changes as they were forced off land, put into schools, and separated from their families, among much more. I am interested in looking at trends among Indians during this time period to see if it is possible to track assimilation through these changes in family structure, population and location of Native peoples from 1880 through 1950. This time period was chosen to give a clear view of the Assimilation Era in its completion and to analyze any trends which may have begun towards the end of this era. I am interested in seeing if there is any link between assimilation of Native Americans and when they were granted citizenship, and to see if this group of people was more or less able to emulate the ideal “American citizen” after years of forced assimilation or if citizenship was granted for other reasons. For these purposes, my dimensions of analysis will be race, migration, family makeup, and population. To track these changes, I will use visuals showing family structure according to number of people living within a unified household, overall population of Native peoples within the United States from 1880 through 1950, and location of Native peoples throughout the United States during 1880 and again during 1950, and historical evidence of factors affecting assimilation at any given time.

Native Americans as a group of peoples changed largely throughout the Assimilation Era. Individual tribes faced specific hardships and underwent adaptions to tackle these hardships, and although looking at Native peoples as a collective group makes it hard to understand these more specific issues throughout the time, there are many similarities between the experiences of tribes across North American. Many scholars have looked at this time period already extensively, although none have looked directly at the link between assimilation and citizenship among Native. However, previous work can help to better understand what was said about the Assimilation Period and how the definition of citizenship, especially in Indian country, has changed through the history of the United States. The Assimilation Era came about as the means by which the United States government sought to assimilate Native peoples to white culture, and therefore to mold them into the perceived image of the ideal “American citizen.” The resources used will focus largely on the idea “citizenship” and how this idea has changed over time within the United States to become more inclusive, and additionally how Native peoples have changed over time to possibly fit more into what an “American citizen” is. Citizenship has been an ambiguous term throughout our history as a country, but seems to have grown overall to become more open to include those people who have assimilated to the agreed upon definition of a “citizen.” This work will focus on how this process has occurred among Native peoples and what other sources have to say about the process of assimilation among Native peoples overall.

Within the United States, those considered “citizens” have been, and continue to be, a growing population of people, which began with mainly white, male landowners, and grew to include almost anyone over 18 years of age. From these somewhat exclusive beginnings, it is important to look at what allowed certain populations to come to fall under the scope of “citizens,” because as Stacy Camp recognizes, citizenship continues to be a defining aspect of American Culture and identity which affects both naturalized and non-naturalized populations within the United States (Camp 2013, 1). Originally, Natives were seen by the ruling British government as colonial subjects, a title which offended the colonists who believed the two groups were vastly different (Piatote 2013). Later on however, the new United States government defined this group of peoples as domestic subjects, a term which was in almost direct opposition to citizenship (Piatote 2013, 8). Throughout this time, the definition of citizenship was constantly changing, to include men over 18 who did not own land, then women, then those who were born or naturalized within the United (which still excluded Native Americans), and so on. Although this definition was growing, so too were the populations of people who were allotted citizenship changing. Although citizenship was indeed becoming more inclusive, groups were still somewhat required to assimilate to fit into American ideals and American culture before they were granted citizenship or considered citizens, and this is especially clear in the case of Native peoples throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Methods

How the data was created

Data from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) were used to create figures one through four. Data from 1880 through 1950 were used with 1% samples. Native Americans were selected from this data set using the IPUMS-created variable RACE, and Alaska and Hawaii were both excluded to ensure the data used would be uniform over time. To look at household sizes, the variable GQ was used to filter out all those living in groups quarters so that only households as defined by IPUMS were included in the data set. However, before 1940, group quarters included large households and households made up of several families which may have an effect on the figures showing household size among Native Americans. Additionally, populations were weighted by PERWT for all years except 1940 and 1950, which were weighted by SLWT. This was done because in 1940 and 1950 the sample for IPUMS was drawn from those who were given the “sample line” version of the census, which included more questions than the regular census forms given our during those years. Additionally, it is important to note that during this time period, enumeration methods were changing between censuses, especially those used to determine race. Therefore, the data may be skewed and underrepresent or overrepresent at times the actually number of Native peoples within the United States.

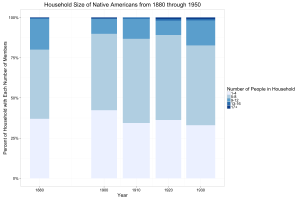

Figure 1 shows the size of Native American households from 1880 through 1930, as data for 1940 and 1950 was not available. IPUMS data provided numbers of people within households up to 48 members within a singular home. In figure 1, however, I have grouped these numbers in order to more easily interpret how household numbers changed throughout the Assimilation Era, as traditional Indian families tended to be larger, composed of extended family, or even with several different families within a single household. Figure 1 shows the number of households with numbers of members from 1-4 members, 5-8 members, 9-12, members, 12-16 members, and 17 or more people living in the household. The figure shows the composition of households as percentages of the total population to show how numbers fluctuated among the whole recorded Native population, rather than representing this population through the mean or median number of people within a household.

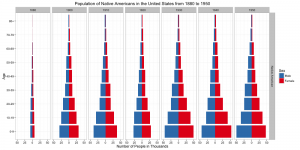

Figure 2 shows population pyramids for people marked as “Native American” in the United States census from the year 1880 until 1950. The population is shown by the thousands, from 0 to 25 and 50 thousand. Male and female populations are differentiated on the graph and ages are separated by every 10 years, until age 80, so that the differences in the population of Native Americans over the years is clear. As before stated and as is very important in population numbers for Native peoples, enumeration methods fluctuated over time and may have caused some changes in data as some Native peoples on reservation we not counted, or others did not fit the current definition of “Native American,” leading to some changes in the data shown.

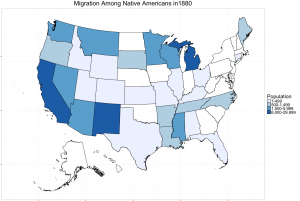

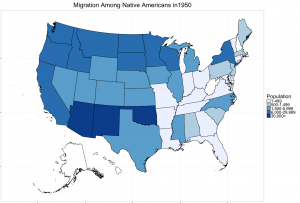

Figures 3 and 4 are maps of Native American populations to show how Native peoples moved around the United States from 1880 through 1950. Birthplace and current residence were both used to show how the location of Indians changed over the time period. Each shade of darker blue shows a larger population of Natives within a state, and these populations are grouped from 1-499, from 500-1,499, and from 1,500-5,999, 6,000-29,999, and 30,000+. Larger populations during this time period were not recorded or more options for population would have been included.

Codes for each code, including the column graph, population maps, and population pyramids, can be found here.

Results and Historical Significance of Data

assimilation and how it applies to citizenship

Assimilation of Native Americans most clearly began with the Carlisle Indian School which was established in 1879 (Calloway 2016, 392). From this point on, Indians began to be formed in the image of the “white American citizen,” largely because, as Stacy Camp argues, a group’s ability to be granted citizenship depended almost completely upon their ability to dissolve into Anglo-American culture (Calloway 2016, 411, Camp 2013, 21). At the beginning of this process, the American government was working to determine how to tackle the so called “Indian problem” and saw only two real solutions, either assimilation or eradication. Clearly the former was taken, though only after determining the latter was not feasible for the time being, and the Assimilation Era that was then ushered in may have allowed Natives to eventually come to be granted citizenship when they were molded enough into the white American image. Thus Indian schools began, which Piatote argues were merely covers for the intolerance at the time, and which spun this intolerance for Indian cultures and peoples as “education” (Piatote 2013, 2). Both Camp and Piatote argue that assimilation was an intentional action taken by the government to fix what they saw as a “problem” and as Calloway affirms, this process may have eventually allowed Native peoples to become recognized citizens, but only after the necessary loss much of their tribal identities.

Figure 1: shows the size of Native American households from 1880 to 1930 according to the number of people within households.

In many traditional Native households, several families or extended family would live within a singular home. This was both for support and because many tribes emphasized the power of the group rather than the individual, unlike within American society. During the assimilation era however, this composition began to change. The government was working towards “remak[ing] Indians in the image of white American citizens” (Calloway 2016, 380). Following the perceived ideals of “white American citizens,” boarding schools stressed the importance of the individual and of advocating and working for oneself, rather than for the benefit of a larger group as was the dynamic within the tribe. Thus, teachers and administrators at boarding schools sought to instate individualistic values in Native children and did so by removing them from their families and tribes, both of which were seen as dangerous influences for young and impressionable Indian children. It was very purposeful then, that many schools were located away from reservations, so that “children could be isolated from the ‘contaminating’ influences of parents, friends and family” (Calloway 2016, 392). Figure 1 shows the composition of Native American households over the years, with each shade of darker blue showing more household members. Although households have not shown significant changes over the time period, the year 1880 shows slightly higher numbers of households with nine or more people than the years following. This is also the year where boarding schools became a growing movement and when children began to be removed from tribes, meaning that families were being split apart more so than ever, possibly leading the next few decades to show slightly smaller Indian families. By teaching them the values of white America and removing them from their families and tribes, boarding schools instilled within children the idea that smaller families based around immediate relatives were the most important. The removal process was pertinent to the movement because it fractured families, and separated children from the larger group of the tribe, completely immersing them in the new culture they were to become a part of in order to become “civilized” (Calloway 2016, 381). However, all too often this meant that it was difficult for children who had gone through the boarding schools to return their tribe, after being “remade” into white citizens. This, however, eventually came to create almost an entire generation of Native children who had been raised in the boarding schools to assimilate to white culture, which meant the entire population of Native peoples was moving towards citizenship through the forced assimilation of this generation.

Also during this time period, Native peoples were being condensed onto reservations to make way for westward movement, a product of the idea of “manifest destiny” which was gaining popularity throughout this era. This paired with the boarding school movement had many adverse effects on Native populations. Before assimilation was accepted as the “answer” to the “Indian problem,” eradication was considered for a brief period, and reservations played a part in this plan. Boarding schools and reservations both were very poor environments and many deaths occurred often undocumented by the government or any administrative organizations. All too often, reservations were cesspools for infection and disease, and through this were somewhat evident of the original solution to the “indian problem”: eradication (Calloway 2016, 328). On reservations Indian peoples tended to be in very dire conditions, and continue to be subject to awful conditions even today. The reservation system, and many of its symptoms, caused Native peoples to become largely dependent on the United States government for their survival. They depended on rations from the government, and subsidized housing and healthcare to survive in the immense poverty that was present on reservations after they had been removed from the land they had known likely for centuries (Harrison 1887, 8). Figure 2 shows that in 1880 and even through the start of the 20th century, the population of Native peoples was in the low thousands according to the U.S. census, although it is important to note that census measures for recording race were often variable and hardly reliable at this time (Calloway 2016, 397). The population of Indians grew throughout the 20th century for the most part, but takes a clear drop in 1920, with all ages showing a notable decrease in population from the decade before. This can perhaps be attributed to the boarding school movement because so many children were lost to the schools, and many died due to harsh treatment, perhaps taking a toll on the overall population. Additionally, as before stated conditions on many reservations were very poor and were often geared towards assimilation in ways that had adverse effects on Native populations, encouraging individualism and the breakdown of the extended family unit for example (Piatote 2013, 1). Although the reservation system was not new, it is possible that its effect on populations was delayed for a couple of generations and only really became clear with children who had grown up there, and were less present in adults who had grown up on traditional land. As the schools began in the 1880s and the reservations had at this point been instated for many years, it is possible that the Native American population shown in the year 1930 could have been the result of these effects, showing a significant decrease. However, as before noted, this decrease could also be the result of census enumeration methods.

Figure 3: shows the number of Native Americans living within any given state, excluding Alaska and Hawaii, in the United States in 1880.

Figure 4: shows the number of Native Americans living in any given state, excluding Alaska and Hawaii, in the United States in 1950.

Additionally, throughout this time period Indians were being relocated and were themselves moving towards opportunities and the centers of Indian life that had been forming by the end of the nineteenth century. By this point it had been some 50 years since Andrew Jackson had instated the Indian Removal Act, through which Native peoples throughout the nineteenth century were moved from traditional tribal lands to reservations where they would be able to learn about what it meant to be a part of larger American society and where they would be out of the way of westward expansion. The government believed that being able to own land, even on reservations, would be a large step in assimilating Indians to more individualistic ideas (DiMatteo 1997, 5). However, this caused little or no change among tribes, as many tribal members thought of reservation land as communal rather than individual. Centers of Indian life due to the reservation system began to emerge by the late 1800s, as shown in Figure 3, and were located largely in western states such as New Mexico, California, and Montana, all of which continue to be home to large populations of Native peoples. After the establishment of reservations by Jackson, it is interesting to note too how the large majority of the Native population of the United States continued to move west even after 1880, as shown in Figure 4, and this may have been due in part to the Dawes Allotment Act (Calloway 2016, 385). The Act was a movement away from the reservation system and towards more clear individualistic ideas of land ownership, by breaking up reservation land into individual holdings. Looking at the map from 1950, Indian populations seemed to spread out very widely, with the exception of Oklahoma. Native peoples continued to be relocated during this time, often in conjunction with the boarding school movement where children were relocated, but also in order to find options for employment or other opportunities. This relocation and spreading out of Native peoples between 1880 and 1950 could speak to the population becoming more integrated into white or American society, and moving towards centers of Native life, but also spreading beyond those. In the post-war era, opportunities abounded even for those who were not white, and for Native who had assimilated into white culture it might have made economic sense to search for jobs and homes away from reservations and centers of culture. This could signify that Native peoples were becoming more assimilated to and accepted in white society, and thus more apt to be granted citizenship.

Much has been written on Native Americans and the Era of Assimilation during the turn of the 20th Century, which began with boarding schools and arguably ended with Native Americans being granted citizenship with the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924. The above four figures shown different possible facets of assimilation and the affects it might have on Native societies. Family structure played a large role in traditional Native cultures, as did knowledge of the land they inhabited. Both of these were affected largely through assimilation, and thus had somewhat of an adverse affect on the population of Native peoples throughout the United States from 1880 through 1950. Although the trends seen could be much clearer and only lend themselves to possible affects, they can help to imagine how the lives of Indians would have been changing during this time.

Conclusion

The definition of “citizenship” has changed throughout American history, from including only those who were white, male and property-owners, to now representing all those who were born or who have been naturalized within the United States. However, as the definition has grown more inclusive, so have certain groups been pressured to assimilate to the mold of the ideal “American citizen.” Native Americans for examples have been clearly targeted throughout post-contact history as “savages” to be molded and integrated into white American society. This was especially true from 1880 through 1930 and even beyond, with the Assimilation Era. Natives were targeted on several levels, three of which were addressed here: family structure, land ownership and location, and overall population. It is somewhat difficult through these variables to see how assimilation may have helped Native peoples to be granted citizenship. Families did become slightly smaller, especially after 1880, although they did not change to a significant enough degree to attribute this change directly to boarding schools. However, the change does correlate with the timeline of boarding schools, and therefore lends itself to a correlation between the two. Native peoples also dispersed widely during this time period, especially when looking at 1950 and where populations resided. This change, more so than the other two, does not correlate with any specific movement during the time, but rather gives off the idea that Native peoples were becoming more integrated in general into white society due largely to assimilation attempts. And finally, populations of Native people during the assimilation era were clearly affected by assimilation attempts, as is shown by a marked drop in the overall population of Native peoples in 1930. However, this too only correlates roughly with the reservation and boarding school movements, and does not lend itself to showing a trackable trend. Although the variables have shown little change over time, when paired with historical context it is possible to see how Native cultures were changing slightly and how Native peoples were reacting to assimilation and growing contact with white society throughout this time period. None of the variables analyzed showed significant changes over the Assimilation Era, but it is possible to understand how Native lives were changing during this time, and how they continued to change even after they were granted citizenship and through the 21st century.

Works Cited

Calloway, Colin. First Peoples: A Documentary Survey of American Indian History. Bedford/St. Martin’s Press, 2016.

Camp, S. L. Archaeology of Citizenship. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2013. Project MUSE.

DiMatteo, Larry A.; Meagher, Michael J. “Broken Promises: The Failure of the 1920’s Native American Irrigation and Assimilation Policies.” University of Hawai’I Law Review 19.1 (1997): 1-36.

Harrison, Jonathan B., 1835-1907. The Latest Studies on Indian Reservations, United States, 1887.

Piatote, Beth H. Domestic Subjects: Gender, Citizenship, and Law in Native American Literature. Yale University Press, 2013.