Marriage Through an Anthropological Lens

In order to first answer the question of how anthropologists define marriage, we checked out a couple introductory anthropology texts from the library, including:

- Cultural Anthropology by Welsch & Vivanco

- Window on Humanity: A Concise Introduction to Anthropology

- Invitation to Anthropology

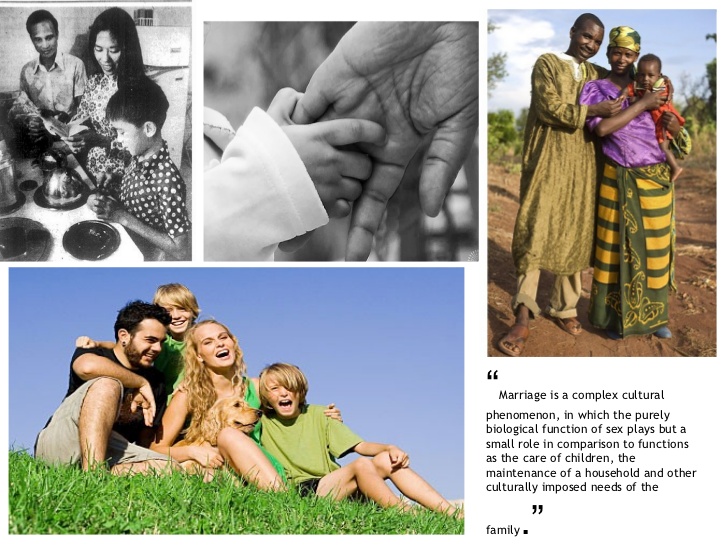

From these texts, it became evident that anthropologists struggle just as much as we did when it comes to determining a clear, universal definition for marriage. This is because a universal definition really doesn’t exist: marriage is complex and takes on many definitions and diverse practices around the world.

Marriage can be a legal contract, a religious covenant, and a social union. It can occur between a man and a woman, two men, two women, a man and multiple women (polygyny), and a woman and multiple men (polyandry). Polygamy is against the law in contemporary North America, but polyandry and polygyny are both practiced in other societies around the world; however, polygyny is far more common. There is no single explanation for polygyny; rather, its context and function vary among societies and even within the same society. For example, in a populous society in Madagascar, plural wives play important political roles; the king’s wives serve as his local agents and are a means of the king giving the common people a stake in the government.

Furthermore, from our research it became evident that marriage greatly differs in Western societies as compared with nonindustrial societies. In nonindustrial societies, marriage can be a means to convert strangers into friends and of creating and maintaining personal and political alliances, relationships of affinity.” This refers to the concept of exogamy; exogamy has adaptive value because it allows the couple to create more widespread social networks. Marriage is more of a group concern in nonindustrial societies; when an individual marries a spouse, they also assume obligations to a group of in-laws. This is in great contrast to marriage in the United States, where marriage is more of an individual matter. This was reflected in my interview with my mom (Kim Gruffi); she said that marrying into my dad’s family was not really a concern for her, and she was excited about creating a new family.

In the US, marriage hinges on the idea that through marriage, a couple creates a new family and they are meant to leave their old families behind as they create a new home for themselves. To an outsider, this would seem extremely strange: Why would the U.S., a country that prides itself on “family values,” encourage the abandonment of families for the creation of independent households?

In addition, it is important to remember that the American ideal of marriage tends to be ethnocentric and neglects the diversity of marriage practices around the world. We tend to think of a “traditional marriage” as that which exists between a man and a woman; however, the idea of a same-sex union is actually not a modern one. For example, there is widespread occurrence of female husbands or woman marriage in many African societies. Among the Nuer, patrilineal pastoralists of Sudan, a woman unable to have children may take a “wife” who enters into sexual relations with a man to bear children.

Two other important terms anthropologists define when it comes to defining marriage are bridewealth and bride service. The concept of bride wealth compensates the bride’s group for the loss of her companionship and labor. It also makes the children born to the woman full members of her husband’s descent group. Bride service also relates to the idea of compensation: among the San/Bushmen community in southern Africa, a new couple typically lives with or near the bride’s family. To compensate the bride’s family for a new home to raise children during the first year of marriage, the man must hunt for the wife’s family. Through this system, marriage ties people into a larger network of people for whom they are responsible.