About Nicaragua: The People of the Autonomous Regions

According to the United Nations, there are approximately 400 million Indigenous people in the world, belonging to 5,000 different groups in 90 countries worldwide. While there is not yet a formally accepted definition of indigenous status, these peoples usually share certain characteristics: (1) they are descended from pre-colonial inhabitants of the region, (2) they maintain traditional cultural and economic practices that are heavily tied to their land, and (3) as a minority group, they suffer from economic and political marginalization.[1]

Within the RACCN and the RACCS, there are three main indigenous groups–the Miskito, the Mayagna, and the Rama–which enjoy different histories as well as different cultural practices.

The Miskito/Miskitu

The most populous indigenous group in Nicaragua, the Miskito have a population of around 200,000. While the Miskito have a native language (which some 180,000 practice), a large percentage of the population also speaks creole English, Spanish, and Rama. Historically, the Miskito subsisted through hunting, gathering, fishing, and gardening. However, as the group is located on the “Mosquito Coast” (which spans from Cape Camaron, Hondorus to Rio Grande, Nicaragua) their economy relies primarily upon fishing and the lobster export industry.

Historically, the Miskito subsisted through hunting, gathering, fishing, and gardening. However, as the group is located on the “Mosquito Coast” (which spans from Cape Camaron, Hondorus to Rio Grande, Nicaragua) their economy relies primarily upon fishing and the lobster export industry. [2] For this reason, a significant portion of the Miskito population has migrated to Corn Island and the Bluefields, which provide plentiful (and lucrative) fishing/lobster yields. According to Encyclopedia,

“The coastal economy in general has been characterized by boom-and-bust cycles; foreign entrepreneurs have periodically invested in rubber, timber, gold, or bananas. When foreign companies were hiring, the Miskito sought labor opportunities; when depressions struck, the Miskito relied on their continuing subsistence agriculture and fishing for support.” [3]

Traditional Miskito society was highly structured, with a defined political hierarchy headed by a king. Power was split among the king, a governor, a general, and (by the 1750s) an admiral. According to the New World Encyclopedia, “historical information on kings is often obscured by the fact that many of the kings were semi-mythical.” [4] Today, as the Miskito people exist in semi-isolated communities along the coast, centralized power has become obsolete; instead, each community is led by their unique Communal Assemblies and Elders Councils. [5] In terms of cultural practices, the Miskito have suffered from a slight cultural “white washing” due to years of entanglement with other cultural groups (both indigenous and non-indigenous). For example, many traditional ceremonies were abandoned when the British introduced Christianity–a faith which they readily adopted. Though they no longer produce traditional Miskito pottery, the group does still craft traditional household utensils/furnitrue out of woven strips of tree fibers and dugout canoes.

The Mayagna

The Mayagna people (typically divided into the Panamahka, Twahka and Ulwa ethno-linguistic subgroups) live in remote communities on the Coco, Waspuk, Pispis and Bocay rivers in north-eastern Nicaragua, as well as on the Rio Grande de Matagalpa in the far south. [6] Lacking a totally unified language, the majority of the Mayagna speak a dialect called ‘Mayagna’ (which is thought to have been born in communities around Rosita and Bonanza). However, this language has been under constant threat due to the proliferation/general shift toward the use of the Miskito language. [7]

Indeed, the Miskito and the Mayagna people have suffered a tumultuous joint-history, characterized by conflict and domination (as evidenced by the Sumo nickname, a derogatory term spread by the Miskito people.) When the British arrived on the Caribbean Coast in the seventeenth century, the Mayagna were divided into a variety of sub-tribes. In the meantime, the Miskito benefitted from friendly relations with the British and (in return for their work as intermediaries between the European power and other indigenous peoples) the group acquired firearms. The armed Miskito frequently raided the Mayagna, often taking captives which they later sold to the British. Later, in the eighteenth century, the Spanish penetrated the Nicaraguan highlights, forming settlements on a large portion of traditionally Mayagnan land. As their population dwindled due to war with the Miskito, disease, and assimilation pressures, the Mayagna were dealt a final blow–at the beginning of the twentieth century the group succumbed to Christianity. In order to preserve the vestiges of their culture that still remained, the Mayagna retreated away from the coast, settling along rivers (and within the Bosawas Biosphere Reserve). [8]

Though there is a lack of information about current Mayagnan population statistics, the general consensus is that the group numbers around 25,000. Today, the Mayagna consider themselves “the custodians of the last surviving primary rainforest in Central America, an area more biodiverse than the US, Canada and Mexico combined,” often relying on the Bosawas’ resources (as well as sustenance farming) to survive [9].

The Rama

Though small in number (around 2,000) of Rama remain in Nicaragua, the indigenous group still boasts an incredibly rich cultural tradition. Location primarily in the isolated land of the Bluefields, the Rama consistently reject millions of dollars from multinational corporations in order to preserve their ancestral lands. [10] While the Rama vigorously protect traditional practices (such as canoe and house construction), recently their langauge (“Rama Cay Creole”) has come under duress. Today, less than 1% of Rama (primarily community elders) speak the language.

Sources:

[1] Welker, Glenn. “Indigenous Cultures.” Indigenous Peoples Literature. September 28, 2016. Accessed October 20, 2016. http://indigenouspeople.net/.

[2] http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Indigenous_peoples_of_the_Americas

[3] http://www.encyclopedia.com/places/latin-america-and-caribbean/nicaragua-political-geography/miskito

[4] http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Indigenous_peoples_of_the_Americas

[5] https://vianica.com/go/specials/32-current-indigenous-communities-of-nicaragua.html

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sumo_people

[7] https://intercontinentalcry.org/indigenous-peoples/mayagna/

[8] http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/41/index-hn.html

[9] https://aeon.co/essays/what-does-progress-mean-for-the-mayagna-of-nicaragua

[10] http://www.bizarreglobehopper.com/blog/2015/01/13/indigenous-people-of-nicaragua-the-rama/

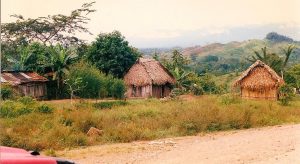

Featured Image: Jungle House, Rosita Nicaragua by Adam Cohn