Isabella Jacoby

SPAN 7 – 17W

Professor D. Moody

3 March, 2017

Response Paper #3 – Who Authorizes Public Art

Rivera’s Symbolism as a Barrier to Revolutionary Thought

The idea that art must be “authorized” to be public is a trait of a bureaucratic society, and can be a problematic manifestation of a government in which moral judgement is institutionalized. Art is a visual or aesthetic expression of the human imagination, and in any place that free speech is held sacred, the publication of art should be as well. However, when an artist wants to reach a truly broad audience, such as the population of a nation or city, the involvement of additional parties becomes necessary. Such was the case with Mexican painter Diego Rivera and his famous murals. For Rivera, public art was authorized by financially, politically and socially powerful people – himself included. In post-revolutionary Mexico, his commissioned murals became state-sponsored attempts to create a national identity. The goal of this state art, and of state-sponsored art in many cases, was to inspire unity and nationalism among a population. While this has proven effective over many years, public art will always have the additional potential to flatten a complex subject by codifying one version of the truth. In order to appeal to and reach a broad audience, Rivera’s public art in particular made use of a popular vocabulary of images and widely-known symbols, such as political figures and stereotypes of people. This use of an iconic visual lexicon to reach an audience signifies a potential problem with public art. While Rivera’s murals were able to write a national story that would speak for the people, there is less proof that they were able to inspire individual thought and “active” contemplation. The publicity of art, especially when sanctioned by the state, has the potential to flatten not only the ideas in a work but also the audience that receives them.

In the 1930s, Diego Rivera received several important mural commissions from the Mexican government that involved depicting the “epic of Mexican history”. It was around this time that Orozco, as well, was being asked by the government to create these visual manifestations of the Mexican story. The two artists, who had developed distinct styles and personas, were now being asked by the state to create the first formal pictorial versions of the Mexican story. This attempt to create a modern national identity would emerge from the necessity of unifying the culture of post-Revolution Mexico during the time leading up to World War II when the imperial imposition of culture from Europe and the “Western” world was a real threat. The publicity of Rivera’s art reached heights it had never seen before, and two particular mural commissions were crucial points in his work. The murals he painted at the National Palace and at Cortez Palace in Cuernavaca were both vast chronicles of Mexican history in which he attempted to summarize hundreds of years on one or two walls. Both works included Rivera’s honed array of political figures and stylized depictions of distinct socioeconomic and ethnic groups.

In his murals at the National Palace in Mexico City, which is shown in Figure 1, Rivera covered three large walls with a chronological account called The History of Mexico. This work, painted between 1929 and 1935, signaled the “real beginnings” of the institutionalization of Mexican mural art. (Rochfort 84) It was here that the public could truly see Rivera’s refined pictorial representations of Mexican themes. Much like the existing traditional rhetorics of European art – which included the countless renditions of the virgin Mary, floating cherubs on Italian ceilings, dramatic ethereal nudes, and stern Flemish women – Rivera was creating a rhetoric for Mexican art. In essence, he gathered meaningful symbols and created a language for the Mexican people to speak to the world through their art and culture. In The History of Mexico, Rivera writes fluently with this vocabulary.

As shown in Figure 2, on the North wall within the palace is a depiction of Pre-Colombian Mexico. This Mexico is painted as a “Golden Age” without conflict despite the harsh realities of certain indigenous rituals and practices. (Rochfort 85) The indigenous people are portrayed with dark skin and white clothing, often in profile or in positions that evoke ceremonial traditions. A temple rises in the background, and a volcano spews tongues of fire under a sun that gazes down with large eyes. A priest-like figure rides a sort of white dragon in the sky. The arrangement uses narrative to bring history to life in mythical form. Even in the panels that depict life after Colombian conquest, this mythical narrative style is still in use. People appear in frieze-like hierarchical levels, assembled with others in the same racial, social, or historical groups.

The middle panel, which can be seen in Figure 3, shows events from the conquest of the Aztecs to the revolution in the early 20th century. The indigenous are shown on the bottom, thrown into chaos by the Europeans. The struggle against oppression is a constant theme throughout the mural. To represent this, Rivera uses iconic figures from history such as Obregón, Calles, Villa, Zapato, and Cabrera who stand for key moments and energies in Mexico’s history of revolution. In the South panel, Karl Marx is shown clearly leading a utopian Mexico in a reflection of Rivera’s vision the country’s recent past and future. The people, events, and clothing in the fresco are all objects which are clearly recognizable by the Mexican public. They symbolize certain ideas: for example, the “Tierra y Libertad” banner in the middle panel, a detail of which is shown in Figure 4, encapsulates the “spirit of the agrarian revolt”. The oil rigs behind the figures of the revolution refer to worship of modernity during the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz. The many revolutionary figures, alongside men in sombreros and bandoliers, clearly represent the Mexican Revolution. (88) Rivera used his system of symbols here to give the Mexican public an ideological language with which to speak about their past, present, and future.

The existence of a national visual vernacular is essential to Mexico as it is essential to any country. Around the world, organized nations incorporate symbols of their history into holidays, media, and even education. The fact that most Americans recognize their flag, their Constitution, the faces of their founding fathers and images of their civil rights movements holds the country together even in a huge nation with vast differences. Rivera used these symbols to create a record of the peoples’ struggle. Sponsored by the government, the Mexican mural movement was a powerful way to connect their people through giving them recognition and pride in the things that made them Mexican. However, the figures depicted in Rivera’s murals are either exact portraits or vague stereotypes. Mexico’s everyday people are always the latter, depicted as resistant hoards of workers that embody the revolution and the spirit of the country. Rivera’s Communist and utopian visions played a key role in this aspect of his work, as he glorified crowds and the laboring class. But such a heavy use of symbols and repetition in public art raises a critical point. Art that is based on accepted visual phrases and traditional narrative accounts – particularly ones that have already been seen before – often lacks the personal impact to compel individual free thought, which is crucial as a catalyst for change.

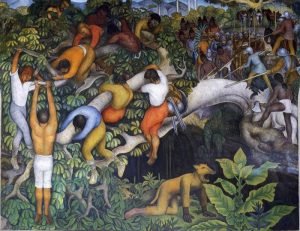

In her book “How a Revolutionary Art Became an Official Culture,” art historian Mary Coffey asks the question: “Do certain visual idioms lend themselves to passive contemplation and thus to political conformity? Or can an artist, through innovative formal means, activate the viewing subject and thereby fulfill mural art’s utopian claim to be a weapon for social change?” (Coffey 2) The “idioms” that so often appear in public art seems to have a problem fulfilling this claim. Because Rivera’s murals were commissioned by the state and because they were so public, he had to create something that spoke to all Mexican people. To do this, he created a vocabulary of visual symbols that communicated important nationalist ideas. By doing this, he was able to help establish a strong Mexican identity. (Rochfort) However, Rivera’s public art in Mexico, consistently fails to defy existing social stereotypes and traditions, and rather embraces and exaggerates them. For example, a detail of the Cortez Palace mural in Cuernavaca can be seen in Figure 5, in which Rivera incorporates clear delineations of race and social roles. By commissioning these murals, the Mexican government meant to express that they supported and encouraged the freedom to embrace Mexican and mestizo identities rather than a prestigious political ideal. However, considering the History of Mexico and murals like it as having revolutionary power to inspire change and artistic freedom of thought is naive. Rivera may have helped strengthen a culture that had been revolutionized from its previous state, but his large-scale murals like the History of Mexico were too steeped in symbolism to plant any lasting seeds of free thought. The “utopian claim to be a weapon for social change” can never be realized when art speaks to individuals exclusively through popular visual imagery. In his works that were authorized by the state, Rivera’s use of symbolism crowds out any space for personal themes that would profoundly impact the individual, and neglects to provide any context for the peoples’ power of free thought. For this reason, the publicity of his art and of many other works, deeply hinders its ability to reach individual people and therefore to inspire truly new and revolutionary ideas.

Works Cited

Coffey, Mary K. How a Revolutionary Art Became Official Culture: Murals, Museums, and the Mexican State. Durham: Duke UP, 2012. E-Duke Books. Duke University Press. Web.

Rivera, Diego. The History of Cuernacava and Morelos – Crossing the Barranca. 1929-30, Cortez Palace, Cuernavaca.

Rivera, Diego. The History of Mexico. 1929-1935. Fresco. National Palace, Mexico City.

Rochfort, Desmond. Mexican Muralists: Orozco, Rivera, Siqueiros. San Francisco: Chronicle, 1998. Print.