The Ideal Child

My cousin Jayden, born to Vietnamese and Chinese parents, appeared to be able-bodied at birth. However, we quickly realized that Jayden wasn’t hitting his milestones. His neck couldn’t support the weight of his head. He barely spoke, aside from a few incoherent babbles. He couldn’t sit without the support of a pillow. My mother would whisper to my father behind hushed doors, “There’s something wrong with him.”

Jayden was diagnosed with Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) shortly after he lost his ability to eat, speak, and walk. My aunt’s Chinese mother-in-law was devastated that her only son had fathered a disabled child. She desperately wanted to carry on the Auyeung family name, so she told my aunt she would pay her to have another child. My aunt refused. I was appalled by how my aunt’s mother-in-law was so quick to seek a replacement for her disabled grandson. If this was how Jayden (a half Chinese American) fared, then what was the fate of disabled children in China—a country with an extensive history of marginalizing minorities?

Although I did not expect disabled children to be warmly embraced by Chinese society, I did not realize the extent of neglect they faced until I stumbled upon two viral social media posts. In November 2013, Facebook users shared images of He Zili, an eleven-year-old Chinese boy with a mental illness. In the picture, Zili was sleeping on a pile of wooden planks. His face was buried in a thick, matted blanket, but all I could focus on was the chain on his right foot. The chain was just long enough for him to claw himself outdoors so that he could go to the bathroom. Because Zili’s caretakers lacked the money and education to care for him, he became a prisoner of his home.

In October 2017, Weibo users shared a picture of an older Chinese woman crying in court. The caption revealed that Ms. Huang killed her disabled son because she feared he wouldn’t be able to support himself when she died. Ms. Huang received twisted sympathy from Weibo users. @Mayboliang wrote: “I can’t imagine how much pain she went through when killing her son.” An anonymous user commented, “I can’t imagine how much perseverance was required for what she’s done for the past 43 years.” To Chinese society, Ms. Huang was the self-sacrificing victim, who shouldered the burden of raising a disabled son for 43 years. Her son was nothing more than a parasite, leeching Ms. Huang of time, money, and happiness. Because Ms. Huang’s son was unable to care for himself like other able-bodied individuals, society deemed him subhuman, and thus undeserving of life.

They are abandoned

Chinese parents also perpetuate the norm that disabled people are “lesser” humans through their high abandonment rates of disabled children. When researcher Erin Raffety visited two Chinese orphanages, she was shocked to only see “orphans with cleft palates, club feet, spina bifida, cerebral palsy, and heart disease.” Raffety’s experience parallels national statistics: 98 percent of children in Chinese orphanages are special needs. The Chinese government attempted to supplement overrun orphanages with baby hatches, where “parents could legally abandon infants into safe care.” Previously, disabled babies were dumped on the sides of roads, stuffed into trash cans, or thrown head-first into drainage pipes.

They are aborted

Some Chinese parents take the more extremist stance that disabled children aren’t entitled to human life. China does not publicly release abortion statistics, so it is difficult to pinpoint the percentage of disabled children that are aborted; however, a study published in the National Society of Genetic Counselors Journal showcased the perspectives of expectant mothers. 519 Mandarin-speaking individuals were interviewed, a majority of whom were willing to terminate a pregnancy if the child was disabled. They cited health as their number one priority and admitted that it would be “worse to have a child with Down syndrome than an invasive test-related miscarriage.” Many Chinese parents associate able-bodied children as “healthy” and disabled children as “unhealthy.” Rather than investing time and resources into a “defective” child, Chinese parents believe it is better to have no child at all.

Where do these deeply rooted prejudices come from?

These prejudices are not recent developments; discrimination against disabled Chinese children dates back to when Chinese characters were created. Disabled people were initially called “fei ren,” which translates to “disabled garbage person.” In an attempt to be more politically correct, the Chinese government coined the term “can ji ren,” which means “disabled sick people.” Despite China’s lackluster efforts to change the terminology surrounding disability, they have still yet to address the underlying causes of disability stigma. There are many theories that attempt to explain why disabled Chinese children are so negatively perceived; scholars cite cultural reasons relating to family reputation, societal norms, imperfection, and academic excellence. However, it is possible that Confucianism perpetuates discrimination against disabled Chinese children by portraying the disabled as subhuman.

Although no research states how many people practice Confucianism, the religion has an impact on every Chinese citizen. Within the last decade, the Communist Party of China has declared Confucius’s birthday a national holiday, published Confucian blogs and websites, and built Confucian statues on school campuses. As a result, Chinese society has come to embrace the social order and harmony that Confucius preached.

Confucian beliefs have also been skewed to present disabled individuals as “lesser” beings, deserving of discrimination. For example, Confucius outlines Five Cardinal Relationships, one of which is that “the son is expected to respect and care for the family.” After 18 years of feeding, clothing, and housing their children, Chinese parents expect their children to care for them after retirement. However, some disabled children may need their parents to care for them even as adults. Because disabled children cannot uphold societal expectations, Chinese parents view the disabled as “inferior.”

Furthermore, Confucius championed the importance of “face” or the idea of social worth and reputation. Professor Chow Lam, who teaches at Illinois Institute of Technology, accurately summed up how the Chinese perceive disability in relation to face: “A disability or any other deformity is a serious loss of face, damaging the social power of the family. A faceless individual is powerless to interact with society.” By referring to disabled individuals as “faceless,” Lam suggests that disabled individuals have no social worth and instead taint the family name.

“A disability of any other deformity is a serious loss of face, damaging the social power of the family.” – Professor Chow Lam

Perfect children only

One of the most concerning aspects of Confucianism is its emphasis on academic excellence and perfection, which is often used to show the inadequacies of disabled Chinese children. Even my Americanized mother, who grew up in a Confucianist household, constantly reminded me to be the smartest, most hardworking student. Hence, my mother always frowned upon how Jayden couldn’t read. She agonized that Jayden was falling behind his peers and insisted that any proper parent would “read to their child every day until he could do so himself.” My mother’s desire for Jayden to academically excel stemmed from the Confucian belief that children should “honor the family through personal accomplishments.” In Confucius’s time, Chinese children studied for civil service exams in hopes of securing a government job. Today, Chinese children attend college in hopes of attaining a respectable job such as a doctor or engineer. Chinese parents fear that a disabled child would be unable to fulfill the role of a perfect, academically driven child. In fact, a study in the National Society of Genetic Counselors Journal revealed that parents “expressed aspirations that their child would be smart and concerns that it would not be normal.” Their responses highlighted the Confucian belief that families must maintain “face” by raising a child who will uphold societal standards of intelligence and honor.

Confucianism also stresses the importance of perfection, and thus has shaped the perception of an “ideal child.” China’s high abortion and abandonment rates speak to a society that views disability as less than ideal—the opposite of perfection. In fact, perfection was taken to such extremes that China became a society that practices eugenics. This was first seen in China’s 1995 Maternal and Infant Law, which barred disabled individuals from reproducing to “prevent new births of an inferior level.” The law also forced women to terminate a pregnancy if the baby exhibited a severe disability. Not only did the Maternal and Infant Law dehumanize the disabled, but it denied children the right to life at the first sign of imperfection. Although religions such as Christianity look down upon abortion, no such stigma exists in Confucianism. Aborting a disabled child is a way of alleviating parents of an unwanted burden and giving them another chance to have a more desirable, perfect child.

Disability in the one-child policy

China’s one-child policy was another example of how the Confucian-based government encouraged parents to abort “imperfect” children. In 1979, the Chinese government adopted the policy because it feared that the population was growing too quickly. Families could only have one child—with several exceptions. For reasons linked to Confucianism, an overwhelming number of baby girls were aborted. Families prioritized having a baby son because Confucius believed that the second most important relationship (after ruler-subject) was between the father and son, who would carry on the family name. Confucius made no mention of the relationship between the father and daughter. Scholars have focused mainly on how female babies were a victim of eugenics; however, they fail to note how disabled people fared during the 34 years the one-child policy was in effect. The one-child policy has only one line that addresses disability: “parents are allowed to have a second child if the first is disabled.” This exception suggests that disabled children hold no value in the eyes of the Confucian-grounded Chinese government. The family is seen as an object of pity, deserving of another chance to have a more worthy child. Thus, Chinese religions create unreasonable standards for an ideal child and enforce policies that systematically dispose of and discriminate against disabled children.

Future outcomes of disabled Chinese children

Disabled children that defy abortion rates and survive ramshackle orphanages become disabled adults who battle the Confucian-based stereotype that they cannot academically excel. If a disabled individual is fortunate enough to be educated (a 2013 Human Rights Watch report estimates that 43% of disabled Chinese individuals are illiterate compared to the 5% national average), she will apply to universities. Unfortunately, China is a communist state, which means the Confucian-grounded government has a large say in the college admissions process. The government not only mandates disabled students to disclose their disability in applications, but it has also created guidelines to advise universities on the types of disabilities that would prevent a student from excelling academically. Rather than looking beyond a student’s disability, the government is more concerned about maintaining the reputation of the school. A disabled student is considered a flaw in China’s academic system, so the government allows universities to reject qualified students based on disability.

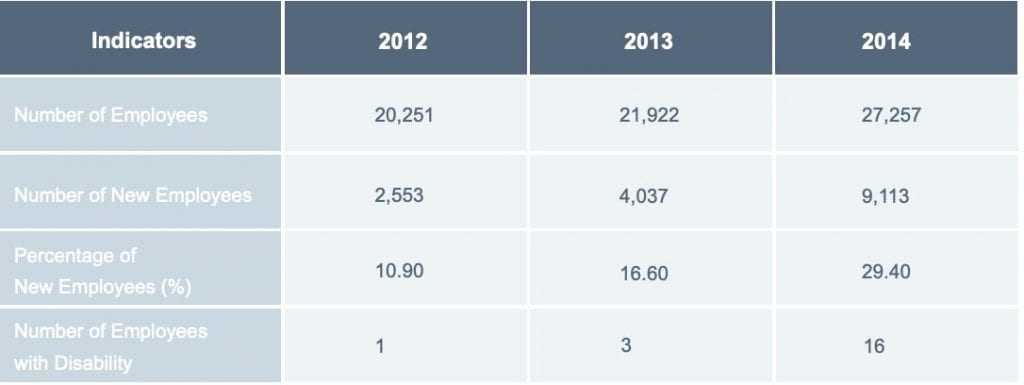

Disabled individuals that do earn a college degree must then live up to the Confucian expectation of perfection in the workplace. Many employers assume that disabled individuals are inadequate workers who hinder company productivity. As a result, only 9 million out of 85 million disabled individuals (6.5 percent) in China are employed. The Chinese government established a quota that 1.5 percent of workers must be disabled, but I was skeptical that this quota was enforced. I confirmed my hunch by reading the 2013 Corporate Social Responsibility Report of Alibaba, one of the largest companies in China. In 2012, 1/20,251 Alibaba workers were disabled. Representation increased in 2012 (2/21,922) and 2013 (16/27,257), but disabled individuals still made up less than 0.06 percent of Alibaba’s workplace. Alibaba’s lack of representation has prevented disabled individuals from proving that they can perform just as well as their able-bodied co-workers.

What can we do?

Misguided religious beliefs have been ingrained in Chinese society for centuries, shaping discriminatory attitudes that disabled children are “lesser” beings. These attitudes continue to influence culture and policy that shun the disabled, rendering them unable to seek higher education and employment. The Chinese government has little intention of reversing these norms. Adoption is the only hope for millions of disabled Chinese children seeking a better life.

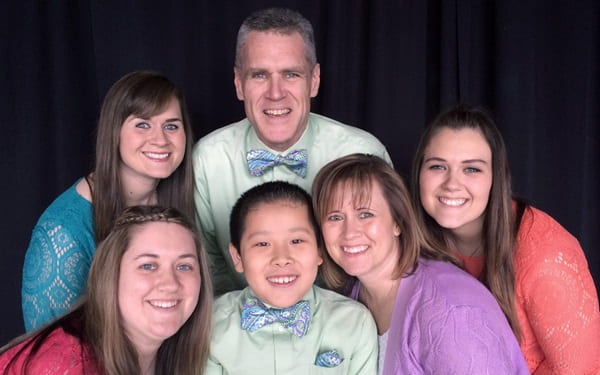

Jiajia was one of the millions of disabled Chinese children waiting to be adopted. He was abandoned and sent to Alenah’s Home orphanage after his parents discovered he had spina bifida. Although Jiajia was eventually cured, his surgery paralyzed him from the waist down. During a CNN Hero segment, Jiajia told reporters that “his dream was to have a family.” After the segment aired, the family that wanted to adopt Jiajia received $36,000 in donations—enough to cover the adoption fee. A CNN reporter checked in with Jiajia a year later “to see him with his family and friends, smiling and laughing.” Through adoption and donation efforts, we can show other disabled Chinese children that they are not forgotten; they are loved.

Click here to donate to Alenah’s Home, a non-profit organization based in St. Louis, MO. Donations will help disabled Chinese children receive medical care and rehabilitation training.