In this investigation, I examine whether or not immigrant groups who had arrived in America before 1930 are able to benefit from professional mobility. I do so by considering data on occupational earnings and education quantile scores from the 1900 to 1930 censuses. I address whether or not mobility existed in a specific rregion-time combinations for certain groups while also considering how access to professional mobility might have changed over time, as measured by these indicators.

Background

Given America’s reputation as a country of immigrants, it should not come as a surprise that factors associated with America’s economic greatness, including hard work, thrift, unrelenting progress, have long been associated with the journey experienced by many of the newest Americans.

Adelman and Tolnay (2003, 182) speak of the preference that certain groups of immigrant workers received over minority Americans for certain jobs. This was largely the result of an employer’s earnest belief that immigrants (often those from particular countries) are uniquely qualified for a job on the basis of their country of origin (ibid.). Be that as it may, the American Dream relies on more than just the aforementioned leg up; it requires the possibility of social mobility across and within generations. Those who work hardest should be able to ascend the proverbial ranks.

The question becomes: can an individual who betters himself truly make it? This investigation explores this in further detail, particularly in the context of first-generation American immigrants. Nevertheless, it is difficult to do so objectively and quantitatively. As unfortunate as this may sound, one way to take stock of the professional and social mobility of a group is to compare it to a reference group that is doing more poorly in these areas, noting the differences. Adelson and Tolay (2003, 179), find that the greater white collar employment rate and average SEI score for immigrants (when compared to black Americans) immediately following the Great Migration points to a greater access to opportunity and professional mobility. The disparities indeed narrow by the end of the century.

I will be using the population of workers in 1950 (who would have uniformly distributed scores for the 1950-basis occupational standing by earnings and education) as my reference group, knowing that this group better approximates the total population for a given year, as we move forward in time. This choice was made as a result of IPUMS’ choice of base year for generating these metrics.

Data and methodology

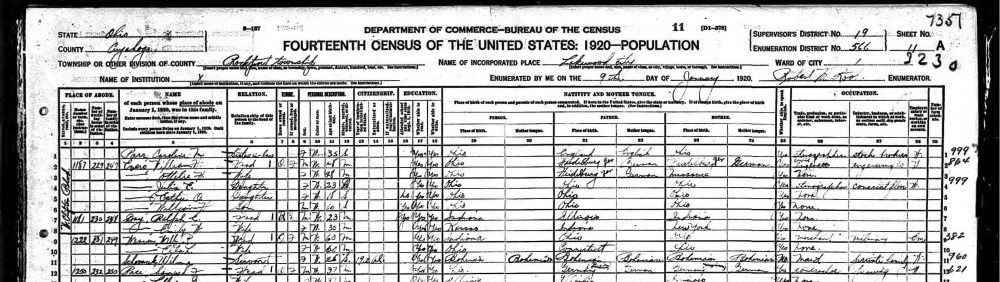

I turned to the Integrated Public-Use Microdata Series, using census samples from 1900 through 1930. I used the 1% sample provided by IPUMS for each year studied. Before any further stratification, I filtered the dataset to only include individuals with birthplaces outside of the United States and any other outlying territories or possessions.

I chose this time frame because all four of the censuses conducted within it asked immigrant respondents for their year of immigration. Although its accuracy may be effected by prevalent attitudes on immigration (or rather the effect of these attitudes on self-reporting), this variable is consistent in its definition across all years, with the relevant questionnaire text never changing in a material way. From this variable, I was able to construct a years-since-immigration estimate for every immigrant. I factored the resulting estimate by rounding the values it produced to the nearest five year interval. This was done to make the cohort-level spineplot analysis more understandable and meaningful.

The other two variables worth noting are the 1950-basis occupational education score and the 1950-basis occupational earnings score, which serve as my outcome variables. For a given occupation in any given year, these occupational standing variables represent the quantile rank of the mean outcome among workers of that occupation in 1950 (i.e. the quantile rank of the mean earnings of plumbers). Although use of these scores has garnered some academic controversy, Sobeck (1995, 49) highlights some misconceptions about them. A major claim is that they are distorted by changes in job definitions over time. Sobeck (1995, 51) refers to an earlier article that showed this concern to be empirically insignificant. Indeed, Sobeck highlights that this concern (which is at the root of many others) is far less significant for censuses before 1950 than for those conducted in 1960 or later.

This class of metric is valuable for a number of reasons. It allows us to proxy for these outcomes when I cannot access this information for all years in a comparable way (i.e. when considering the 1900-1930 time frame). It is a quantile measure, eliminating the need to account for factors such as monetary or academic degree inflation. Most importantly, it is resistant to the effect of any discrimination in the actual wages paid to immigrants or any level of educational over-qualification. In this sense, these occupational standing variables help highlight the class of opportunities immigrants are receiving rather than simple raw outcomes. Sobeck (1995, 49), touches on this, stating that “although the income score is derived from individual-level data, it should not be interpreted as actual income […] an occupation with a good score is well-rewarded and probably high-status”. Even with its limitations , this metric of occupational standing is often seen as a superior alternative to SEI and other “subjective” scoring models (Sobeck 1995, 50).

The stratifying variables not worth mentioning in great detail consist of geographic region of residence, gender, citizenship status, and year. I considered adding continent of birth, but the effect that stratifying by another variable would have on computation times led me to eliminate that option.

The filtered data was then used to generate a spineplot on the basis of years-since-immigration and the chosen outcome measure. As mentioned previously, individuals were grouped into cohorts on the basis of these metrics. Outcome scores were split into quartiles and years-since-immigration was rounded to the nearest five year interval. The proportions of individuals represented by each outcome quartile (of all individuals within a given years-since-immigration cohort) were plotted. Doing so controlled for disparities in the number of immigrants across these cohorts.

Results

Link to interactive heat map of professional mobility

Given the nature of occupational standing scores, it is not particularly meaningful to consider absolute quantities. After all, what numerical bearing does the quantile earnings rank of a job in 1950 have on workers in that job in 1910? With all that said, I still comment on observable trends, patterns, and under or over-representation based on what I see in the various spineplots. Indeed, in order to infer over or under-representation, I must make the plausible assumption that the score quartile cutoffs from 1950 roughly correspond with the quartile cutoffs in each year of analysis. That is to say, I assume a fairly uniform distribution of outcome scores (for each outcome) within every year being considered.

Moving onto my chart, I find that the starting position for immigrants (that is, their outcome within 7.5 years of immigration) becomes more difficult from 1910 to 1930. In all four years, nearly three quarters of those with less than 2.5 years of residency fell into the bottom two earning score quartiles. However, the proportion of those within the bottom quartile increases by almost a half between 1910 and 1930.

Overall, it appears that the prospects of male immigrant workers have improved over time, when I focus on earnings score. Whereas men in 1900 were underrepresented in each of the top two quartiles for all residency estimate cohorts, these proportions improved moderately in 1910. By 1920, those within the top two quartiles exceeded 50% for men who had spent approximately 25-35 years in America. By 1930, I find a fairly mobile picture of the employment market place; when an individual has spent approximately 30 years in America, the odds that they land in any quartile are about 1 in 4. This observation seems to hold true for immigrants when I include women as well. Perhaps if I extended this analysis further into the future, I would find stagnation in improvements, which would support Adelson and Tolnay (2003).

For women only, there are also trends of drastic improvement, although the general deficit in female earnings means that women are generally in jobs in the lower quartiles. Nevertheless, I find that although half of immigrant women in 1900 and 1910 fell in lowest earning score quartile, this number dipped below a half for women who had spent approximately 5-30 years in America in 1920 and 1930.

Other notable observations include the fact that the distributions change (and begin) less dramatically for citizens than for non-citizens. For most region and time combinations citizens also terns to see better outcomes (i.e. higher representation in better quartiles) than non-citizens. The differences are starkest in the top and bottom quartiles. Non-citizens appeared to have the best outcomes in the Northeast and the poorest outcomes in the South. Conversely, citizens appeared to do the best (i.e. proportion in top two quartiles after two decades in America) in these regions.

When I looked to perform an analogous analysis on education, the results were surprising. For most region, year, gender, and citizenship combinations, upwards of 75% of persons represented were in the lowest quartile, with this number slimming down slightly for every census year. The exceptions to this rule included female citizens in the South and West. While it may be the case that many of the jobs requiring education in 1950 simply did not exist in large numbers during the early 1900’s, I did not find this line of reasoning compelling.

The best conjecture I could come up with after looking at the literature, was that immigrants at this time generally did not begin their careers in jobs demanding a high degree of education. Even if they later shifted into more or less demanding jobs (and demonstrated mobility in earnings score) its not likely that they would move into jobs were education was a priority. This finding is sobering in light of Sobeck’s (1995, 51) caution against over-reliance on the earnings score. He notes that it does a poor job in distinguishing white and blue collar workers, which is an area in which the education score might plausibly excel.

Conclusion

Although the results were fairly consistent with the initial hypothesis, it was surprising to see the stark contrast between the earnings score and educational score distributions. Immigrants in all decades appeared to have the opportunity to change their lot in life.

While starting position and the degree of mobility varied by year and region, having social mobility as a male immigrant was as good as a guaranteed. Results indicated that the same could be said (with less enthusiasm) of women; particularly of those with citizenship.

The lack of parallelism with mobility in educational score indicates that perhaps the opportunity granted to immigrants is more one-dimensional than I, as a country, as willing to collectively admit.

Sources

Source code for shiny application

Adelman, Robert M. and Stewart E. Tolnay. “Occupational Status of Immigrants and African Americans at the Beginning and End of the Great Migration”, Sociological Perspectives, Summer 2003; Vol. 46, No. 2, 179-206. Print.

Sobeck, Matthew and Lisa Dillon. “Occupational Coding”, Historical Methods.Winter 1995; 28(1): 70-73. Print.

Sobek, Matthew. “Occupation and Income Scores”, Historical Methods. Winter 1995; 28(1): 47-51. Print