On August 20, 1866, the National Labor Union asked the United States Congress to pass a law mandating an eight-hour workday (Library of Congress, http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/today/aug20.html). After decades of battling with labor unions, on June 26, 1940, Congress finally ceded, officially amending the Fair Labor Standard Act to limiting the workweek to 40 hours (Fair Labor Standards Act, https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42713.pdf). This had a monumental effect on the trend of weekly hours worked throughout the US population.

Some cite that during the same period, the correlation between work hours and wage income has increased (Costa 1998, 1). Furthermore, some attribute the declining wage gap between men and women during the same period to longer work hours for women in the workforce (Mandel and Semyonov 2014, 1598). I am going to argue that the recent increase in correlation between weekly hours worked and wage income is confined to the cohort of White women.

Data:

My data have been collected from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) from the University of Minnesota. I am using 1% samples of the decennial US Census from 1940-1960 and 1990; for 1970 I am using the 1% State Form 1 sample; for 1980 I am using the 1% Metro sample.

IPUMS variables used in the analysis include URBAN to identify the urban/rural status of an individuals residence (residing in a township with a population of greater than 2,500), EMPSTAT to identify the employment status of an individual, HRSWORK2 to identify the hours worked per week for a sampled individual, and INCWAGE to identify the strictly wage income of an individual. IPUMS variables PERWT and SLWT were used to aggregately weight the sampled individuals. SLWT (sample line weight) is used strictly for the 1950 census.

Method:

I manipulated the data to examine the different relationships between weekly hours worked and wage income across urban/rural, and race divides between 1940 and 1990 in order to compare such prevailing trends to the growing connection between women’s working hours and wages during the same time period (Mandel and Semyonov 2014, 1598).

In order to look specifically to individuals in the labor force, I filtered the data to focus on individuals who were between the ages of 18-65, and only surveyed those who were reported by the EMPSTAT variable as currently employed and therefore in the labor force. Next, I separated the individuals in the data into cohorts following their defined urban or rural resident status. I used the Consumer Price Index in order to adjust the reported incomes for inflation to the 2000 level.

The IPUMS variable INCWAGE reports the total pre-tax wage and salary income for each respondent for the previous year. Using INCWAGE I was able to plot the median incomes for each race, sex, and urban status cohort. My R code for the analysis can be found here.

Results:

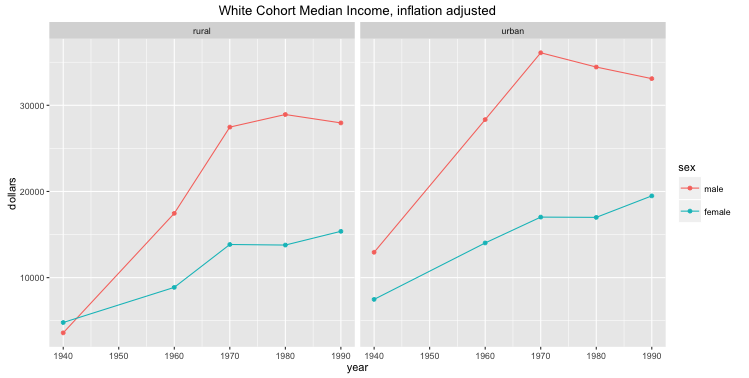

Figure 1:

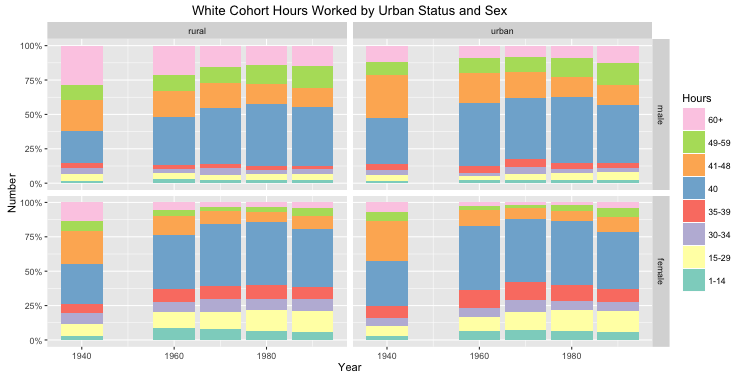

Figure 2:

Figure 1 shows the decennial median adjusted wage income for the White cohort between 1940 and 1990. Seen here is a steep increase in inflation adjusted wage income among urban White men in the labor force between the 1940 and 1970 censuses, and then decline in inflation adjusted incomes from 1970 to 1990. Rural white men experience a similar increase in inflation-adjusted incomes from 1940 to 1980, and then see a slight decline from 1980 to 1990. White women living in both urban and rural regions, however, do not experience a decline in inflation adjusted incomes at any point between 1940 and 1990. Rather, in both the urban and rural cohorts of White women, an increase in median inflation adjusted income is seen between 1980 and 1990, a period during which the median inflation adjusted incomes for both urban and rural White men had dropped.

Figure 2 represents the decennial percentages of White respondents in differing cohorts of weekly hours worked. Here we see the impact of the 1940 amendment to the Fair Labor Standards Act on the weekly hours worked throughout the White cohort of the US population. Although data for the 1950 census are not available for the categories, we see a precipitous increase in the percentages of both white men and white women working 40 hours per week. However, it is important to note that the Fair Labor Standards Act amendment had a larger impact on the ratio of white women working 40 hours per week than it did on the ratio of white men working 40 hours per week. This is especially important to note when considering the stated effect of hours devoted to paid work on the gender pay gap in recent decades. Mandel and Semyonov say, “…gender differences in average working hours accounted for 4% of the total gap in 1970 (less than sociodemographic characteristics and occupations). Only two decades later, in 1990, working hours accounted for one-fifth of the gross gap; and in 2010 working hours already explained one-third of the gross gender pay gaps.”(Mandel and Semyonov 2014, 1607). This explanation is consistent with my analysis of the data, as there is a continuous increase in the median wage income of white women between 1940 and 1970, despite a perceived decrease in the percentage of women working for greater than 40 hours per week. Furthermore, following Mandel and Semyonov’s explanation of the gradual increase in the correlation between women’s working hours and pay, the more recent increase in white women’s wage income shown in the 1990 census can be more so attributed to the perceived increase from 1980 to 1990 in the percentage of white women working more than 40 hours per week.

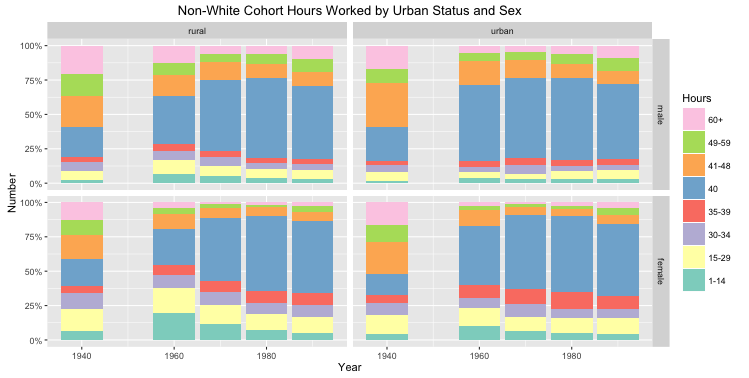

Figure 3:

Figure 4:

Figure 3 shows the decennial median inflation adjusted income for non-white respondents from 1940 to 1990. For non-white men, the trend in this graph differs slightly from that of the same graph for white men. Inflation adjusted incomes for urban, non-white men did not begin to decline until between 1980 and 1990; inflation adjusted incomes for rural, non-white men did not decline at any time during the period analyzed. The observed trend in inflation adjusted wage incomes for both urban and rural, non-white female respondents also differs from that for both urban and rural, white female respondents. Although both urban and rural, non-white women experienced faster increases in inflation-adjusted incomes during the period examined, the decennial rate of increase between 1980 and 1990 is declining compared to the prior year, rather than increasing, as seen in the trend for both urban and rural, white women.

Figure 4 shows the decennial percentages of both urban and rural, non-white men and women in each of the various weekly hours worked cohorts. Although similar general trends exist here in comparison to Figure 2, it seems that the 1940 congressional amendment to the Fair Labor Standards Act had a magnified in both urban and rural, non-white men and women. Observed here is a greater increase in the percentages of non-white men and women working 40-hour workweek after the amendment than white men and women. Furthermore, when comparing this to Figure 2, there is a very similar increase in the percentages of both urban and rural non-white women working greater than 40 hours per week between the 1980 and 1990 censuses.

Conclusion:

The similarities in the most recent (between 1980 and 1990) increase in the percentages of respondents working greater than 40-hour workweeks despite the differing trends in the rates of change in inflation adjusted incomes suggests that the increase in correlation between working hours and wage incomes is confined to urban and rural white women. This more recent trend is different from that observed from earlier in the century by Costa, suggesting an across-the-board increase in correlation.(Costa 1998, 1) Furthermore, Mandel and Semyonov seemingly overlook the difference in the connection of working hours and wage income between white and non-white women (Mandel and Semyonov 2014). The decrease, rather than increase, in the inter-census rate of change in the inflation adjusted wage incomes of non-white women, despite a comparable increase in the percentage of women working greater than 40-hour work weeks, suggests a smaller correlation between working hours and wage income of non-white women. Furthermore, the recent drop in the inflation-adjusted incomes of both white and non-white men despite a similar increase in the proportion of men working greater than 40-hour work weeks between 1980 and 1990 suggests a negative correlation between working hours and inflation adjusted wage income during the period examined.

Works Cited:

2014. “Gender Pay Gap and Employment Sector: Sources of Earnings Disparities in the United States, 1970-2010.” Demography 51: 1597-1618

- “The Wage and the Length of the Work Day: From the 1890s to 1991..” Journal of Labor Economics 18: 156-181

Mayer, Gerald, Benjamin Collins, and David H. Bradley. The Fair Labor Standards Act: A Resource Guide. Fairfax, VA: International Asoociation of Fire Chiefs, 1994. Fas.org. Congressional Research Service, 4 June 2014. Web. 6 Mar. 2016. <https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42713.pdf>.

“Today in History.” : August 20. Library of Congress, n.d. Web. 09 Mar. 2016 <http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/today/aug20.html>.