The Crucible dramatizes one of the darkest moments in American history. Fear mongering became an excuse to hunt down the ordinary citizens of Salem, Massachusetts, in order for the Puritanical leaders to maintain strict control over their town. Those responsible for such heinous acts used terror and separation to antagonize people they had known their whole lives. Among the townspeople characterized in the Miller’s play, only one is black. Tituba, the slave of Reverend Parris and a native of Barbados, stands alone in the town of Salem. Numerous scholars have studied Tituba, identifying her for the contrast she gives to the rest of the white Puritans. However, her place in history often takes on that of the instigator, and she faces blame for the events in Salem to this day, described by some as “a dark icon of American mythology.” [1] This blame has no justification, and the amount of attention and criticism Tituba has received by historians stems from her difference in race above all else. In Miller’s play, he individualizes Tituba in terms of her dialect, place of origin, and skin color in order to show how individuality can be subverted into a cause for fear. Miller characterizes the preconceived difference between black and white as it would have appeared in Salem, but also as it has appeared throughout American history until his time. Miller also reminds the audience that while Tituba faces subjugation because of her race, she holds an unusual power over the people in the town.

The racial individuality of Tituba in The Crucible gives her a place unmatched by any of the Puritans in the play. Amidst a large cast, she stands alone as the only character from outside New England, the only character who speaks differently than everyone else, and the only character with one name. [2] She stands apart from the rest because of her race and the associations that she draws from the audience when seen amid the townspeople of Salem, among them her fractured English and voodoo. However, despite her individuality, she holds no true agency against the other characters of the play. While the theatrical world often utilizes individuality to contrast the crowd, Tituba remains invisible and her voice stays silent as a result of her race. However, despite Tituba’s invisibility in the action of the play, she has gained notoriety in the historical record. Among the many victims of the Salem Witch Trials, restitution and exoneration were offered to the families of almost all victims. Tituba remains, however, as a symbol for the horrors and injustices that occurred. Even today, some historians still argue Tituba should be “blamed for the start of the trials” and her perceived ignorance evokes accusations of Satanism. [3] While all of the white victims of the trials have been absolved of their frivolous charges, the historical record still singles out Tituba as the primal instigator. Miller utilizes this individuality as well as the general state of American racial prejudice in order to show how Tituba stands apart from the crowd. [4] She receives different treatment, faces different criticism, and gains her small amount of power from the trials in a way that contrasts the experience of everyone else. Miller symbolizes all of these inconsistencies using the same method that Americans have for centuries, in the difference between blackness and whiteness.

The racial individuality of Tituba in The Crucible gives her a place unmatched by any of the Puritans in the play. Amidst a large cast, she stands alone as the only character from outside New England, the only character who speaks differently than everyone else, and the only character with one name. [2] She stands apart from the rest because of her race and the associations that she draws from the audience when seen amid the townspeople of Salem, among them her fractured English and voodoo. However, despite her individuality, she holds no true agency against the other characters of the play. While the theatrical world often utilizes individuality to contrast the crowd, Tituba remains invisible and her voice stays silent as a result of her race. However, despite Tituba’s invisibility in the action of the play, she has gained notoriety in the historical record. Among the many victims of the Salem Witch Trials, restitution and exoneration were offered to the families of almost all victims. Tituba remains, however, as a symbol for the horrors and injustices that occurred. Even today, some historians still argue Tituba should be “blamed for the start of the trials” and her perceived ignorance evokes accusations of Satanism. [3] While all of the white victims of the trials have been absolved of their frivolous charges, the historical record still singles out Tituba as the primal instigator. Miller utilizes this individuality as well as the general state of American racial prejudice in order to show how Tituba stands apart from the crowd. [4] She receives different treatment, faces different criticism, and gains her small amount of power from the trials in a way that contrasts the experience of everyone else. Miller symbolizes all of these inconsistencies using the same method that Americans have for centuries, in the difference between blackness and whiteness.

The Crucible serves as a historical drama, and it offers a strong emphasis on the symbolism behind being black and being white in Puritanical and contemporary America. Even before Tituba confesses that “the Devil got him numerous witches,” she has already been associated in Salem with evil because of the color of her skin. To the Puritanical leaders that ran the town, “God’s condemnation was visible in the color of her skin.” [6] This condemnation remains evident throughout the play in the way that Tituba receives treatment. The black slave of Salem already brings connotations of the devil with her, so her admission comes as little surprise compared to the numerous white characters who face accusations of congress with the devil. Miller allows Tituba to buy into this reality fully in the play. By condemning her own blackness, she can offset some of the blame onto the whiteness of those she accuses. Reverend Parris and his cronies presuppose her association with the devil, but her revelations on the state of her white neighbors are much more shocking. When Tituba describes her encounter with the devil, she says, “It was black dark,” in order to show how her blackness evokes evil throughout the play. [7] In the historical records of Tituba’s testimony, it states that she described the devil as a tall man from Boston, wearing black, who had white hair. [8] This description seems to describe both her master, but also the clergy as a whole. The Crucible shows how the evil associated with blackness is merely present by association. Conversely, the abhorrent actions of the characters who accuse and kill their neighbors show how evil can just as easily become associated with the whiteness and purity of the Puritans. In the historical context of the play’s debut, not much had changed. “The history of witchcraft in The Crucible is a struggle between wrong and right; the history of McCarthyism is a struggle between left and right; but the history that is obscured by both of these other histories is the struggle between black and white.” [9] The division between blackness and whiteness remains as real today as it did during McCarthyism and the Salem Trials. The association between blackness and evil have persisted, regardless of the lack of justification for it.

The Crucible serves as a historical drama, and it offers a strong emphasis on the symbolism behind being black and being white in Puritanical and contemporary America. Even before Tituba confesses that “the Devil got him numerous witches,” she has already been associated in Salem with evil because of the color of her skin. To the Puritanical leaders that ran the town, “God’s condemnation was visible in the color of her skin.” [6] This condemnation remains evident throughout the play in the way that Tituba receives treatment. The black slave of Salem already brings connotations of the devil with her, so her admission comes as little surprise compared to the numerous white characters who face accusations of congress with the devil. Miller allows Tituba to buy into this reality fully in the play. By condemning her own blackness, she can offset some of the blame onto the whiteness of those she accuses. Reverend Parris and his cronies presuppose her association with the devil, but her revelations on the state of her white neighbors are much more shocking. When Tituba describes her encounter with the devil, she says, “It was black dark,” in order to show how her blackness evokes evil throughout the play. [7] In the historical records of Tituba’s testimony, it states that she described the devil as a tall man from Boston, wearing black, who had white hair. [8] This description seems to describe both her master, but also the clergy as a whole. The Crucible shows how the evil associated with blackness is merely present by association. Conversely, the abhorrent actions of the characters who accuse and kill their neighbors show how evil can just as easily become associated with the whiteness and purity of the Puritans. In the historical context of the play’s debut, not much had changed. “The history of witchcraft in The Crucible is a struggle between wrong and right; the history of McCarthyism is a struggle between left and right; but the history that is obscured by both of these other histories is the struggle between black and white.” [9] The division between blackness and whiteness remains as real today as it did during McCarthyism and the Salem Trials. The association between blackness and evil have persisted, regardless of the lack of justification for it.

The individuality of Tituba combined with the associations perpetuated onto non-whites give her a powerful potential in the world of the play. Tituba represents “the embodiment of Africanness in American history.” [10] She holds power, but becomes clouded in invisibility and cannot overcome the confines of a legal system and racial hierarchy that surround and antagonize her. The one moment in the play when Tituba exercises her agency exists only when she initially accuses those around her of witchcraft. She becomes interesting and useful to the white men for a brief time, but after noticing what has happened, the young white girls just as soon usurp her gained power and begin accusing those around them. [11] The Crucible showcases the way that power can be subverted by panic and fear. In the world of the play, the devil and witchcraft serve as the primordial threat to the power held by the town’s Puritanical leaders. In Miller’s world of the 1950s, the fear of Communism similarly threatens the established order, solely because the ideology remains different and obscure. In both of these times, the conception of blackness serves the same purpose. The leading parties of both eras emphasized race to label the differences between themselves and others as a “discernible threat to the stability of the community.” [12] When Tituba exclaims, “I have no power on this child, sir,” she speaks the truth, whether or not she believes her own words. [13] However, Tituba holds a much greater power over the stability of Salem which she does not recognize. Tituba has power in her differences of dialect, origin, and skin color, and she unknowingly utilizes this power by playing into the fear that she evokes among her white neighbors in an effort to save herself. She certainly may not be doing this consciously, but at this early stage in the dramatic action she holds enormous sway over the course of events. Miller utilizes Tituba as a character the way his world has utilized African Americans. She serves as a powerful invisible presence, one which has to potential to shake the foundations of society. In The Crucible, Tituba exists in a way that challenges those who have more power than her, and ultimately shakes them to their core.

The individuality of Tituba combined with the associations perpetuated onto non-whites give her a powerful potential in the world of the play. Tituba represents “the embodiment of Africanness in American history.” [10] She holds power, but becomes clouded in invisibility and cannot overcome the confines of a legal system and racial hierarchy that surround and antagonize her. The one moment in the play when Tituba exercises her agency exists only when she initially accuses those around her of witchcraft. She becomes interesting and useful to the white men for a brief time, but after noticing what has happened, the young white girls just as soon usurp her gained power and begin accusing those around them. [11] The Crucible showcases the way that power can be subverted by panic and fear. In the world of the play, the devil and witchcraft serve as the primordial threat to the power held by the town’s Puritanical leaders. In Miller’s world of the 1950s, the fear of Communism similarly threatens the established order, solely because the ideology remains different and obscure. In both of these times, the conception of blackness serves the same purpose. The leading parties of both eras emphasized race to label the differences between themselves and others as a “discernible threat to the stability of the community.” [12] When Tituba exclaims, “I have no power on this child, sir,” she speaks the truth, whether or not she believes her own words. [13] However, Tituba holds a much greater power over the stability of Salem which she does not recognize. Tituba has power in her differences of dialect, origin, and skin color, and she unknowingly utilizes this power by playing into the fear that she evokes among her white neighbors in an effort to save herself. She certainly may not be doing this consciously, but at this early stage in the dramatic action she holds enormous sway over the course of events. Miller utilizes Tituba as a character the way his world has utilized African Americans. She serves as a powerful invisible presence, one which has to potential to shake the foundations of society. In The Crucible, Tituba exists in a way that challenges those who have more power than her, and ultimately shakes them to their core.

[1] Rosenthal, Bernard. “Tituba.” Magazine of History, vol. 17, no. 4, 2003, 50.

[2] Miller, Quentin D. “The Signifying Poppet: Unseen Voodoo and Arthur Miller’s Tituba.” Forum for Modern Language Studies, vol. 43, no. 4, 2007, 438.

[3] Roszak, Suzanne. “Salem Rewritten again: Arthur Miller, Maryse Condé, and appropriating the Bildungsroman.” Comparative Literature, vol. 66, no. 1, 2014, 114.

[4] Ibid, 118.

[5] Miller, Arthur. The Crucible. Bantam Books, 1963. 42.

[6] Tucker, Veta Smith. “Purloined Identity: The Racial Metamorphosis of Tituba of Salem Village.” Journal of Black Studies, vol. 30, no. 4, 2000, 625.

[7] Miller, Arthur, 43.

[8] Tucker, 625.

[9] Miller, Quentin D, 444.

[10] Ibid, 440.

[11] Ibid, 443.

[12] Ibid, 440.

[13] Miller, Arthur, 41

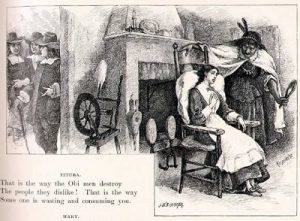

Images: Left: [Tituba Teaching to 4 Children the First Act of Witchcraft]. [No Date Recorded on Caption Card] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <https://www.loc.gov/item/2003663675/>. Right: “Tituba and the Children,” illustration by Alfred Fredericks, published in A Popular History of the United States, circa 1878. Below left: “Look Into This Glass” illustration of Tituba by John W Ehninger published in Poetical Works of Longfellow circa 1902