Abstract

Lorie Loeb, Executive Director of Dartmouth’s DALI Lab, led the panel “Social Media and Social Entrepreneurship in Response to the Earthquakes,” featuring panelists Max von Hippel, Ravi Kumar, Kevin Bubriski, Austin Lord. This panel discussed the means by which various forms of social media played a role in the aftermath of the Nepal earthquake. Max von Hippel discussed his mobile app “Chetawani”, which allows users to locate available resources and receive instantaneous updates about damaged areas. Chetawani also offered verified news stories after the earthquake to prevent the spread of misinformation. Ravi Kumar used social media to make information easily accessible in the aftermath of the earthquake. His Google Doc on verified news, resources, and relief efforts became a widespread tool for citizens on the ground. Kevin Bubriski used his photography and Photo Kathmandu as an example to discuss social media as a forum for diverse perspectives and a platform for giving voice to the voiceless. Finally, Austin Lord reflected on his experience on the ground after the earthquake, and the importance of social media as an archive and a source of immediate relief information. The panelists provided diverse perspectives on the integral role of social media in disaster relief after the Nepal earthquake.

Background and Historical Context

Nepal is considered a high-risk country for seismic events, but the worst earthquake in its history before the earthquakes of 2015 occurred more than 80 years ago, in 1934 (Nepali Times). That earthquake was of a similar magnitude and incurred a similar death toll as the earthquakes of 2015 (Earthquake-Nepal). While Nepal’s geographical location makes its vulnerability to earthquakes inevitable, the consequences of any seismic event there is considerably worsened by the country’s unpreparedness – its physical structures are not earthquake-resistant, and Nepalis are not educated on earthquakes and how to safely react to one.

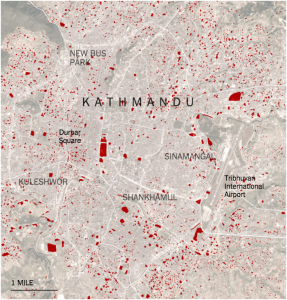

Map of Death Tolls, The New York Times

Nepal is the 16th poorest country in the world; 55 percent of its population of 26.5 million people live below poverty lines, and 37 percent are considered extremely impoverished (Foundation Nepal). The earthquakes of 2015 ravaged Nepal’s already weak economy and killed thousands of its citizens. Economic activities were disrupted and millions were displaced from destroyed homes. Despite its diffuse geographical population distribution – 82 percent of Nepalis live in rural areas – Kathmandu received the majority of relief resources, and rural communities were left to rebuild on their own (Foundation Nepal).

Temporary Shelter Areas in Kathmandu, The New York Times

As the speakers at the panel discussed on this page made clear, social media was instrumental in distributing resources and information in the aftermath of the earthquake. But access to smartphones and the Internet, as well as technological literacy, is limited in Nepal, and was significantly diminished in the aftermath of the earthquake. Developers creating online earthquake relief resources had to devise solutions that would be easily understood and could function on limited bandwidth (NASA).

Ethnography

Throughout the panel, it was interesting to note the audience’s reactions to different panelists. The room was dominated by non-Nepalis. Most of the Nepalis present were seated in the front row. While there were a few undergraduates and Tuck students present, most of the audience consisted of older people – potentially faculty, guests, or community members. The tone of the panel was professional, but the presentations were lighthearted and often humorous. Near the end, the audience seemed to grow restless. The panel went overtime and the later speakers had to cut their presentations short, or rush them.

Lorie Loeb, the executive director of Dartmouth’s DALI Lab, opened the panel with a discussion of social entrepreneurship and social media. Loeb defined social entrepreneurship as the use of business concepts and innovation in solving societal problems and bringing value to society. She asked the audience to question what social media and social entrepreneurship mean, in terms of both economic and societal impacts, went on to introduce the first panelist.

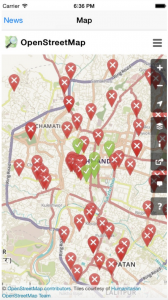

Max Von Hippel, a Dartmouth ’19, discussed his disaster relief mobile application, Chetawani (Nepali for ‘danger’ or ‘warning’). Chetawani contained a curated collection of resources such low-bandwidth RSS feeds for verified news updates and the ‘Quake Map,’ a real-time feature that allows users to view and input information relevant to the earthquake. Over 6,500 users have downloaded Chetawani. Most came from Nepal, in the time directly after the earthquake.

Von Hippel admitted the app has flaws: it was only available for iPhones, limiting the population of people that could access it; there is no translation, causing literacy and tech barriers to emerge; the map downloads slowly and has no filters for its information; and the app lacks a functional offline mode. Von Hippel expressed his hopes to use feedback from the app’s users, along with online tools such as Facebook and Stack Exchange, to improve its utility. He finished by describing his latest app, Chirp Alert! – his next step in working with disaster relief applications.

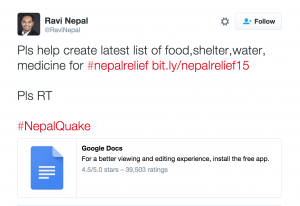

Von Hippel was followed by Ravi Kumar, founder of Code for Nepal. Kumar’s presentation emphasized the importance of complimenting open data with accessible, user-friendly platforms. In the aftermath of the earthquake, he looked to Twitter for information, used Viber to call Nepali contacts for free, and used Google India’s People Finder in the disaster areas. He organized all the information he gathered from these sources and publicly shared them as a Google Doc. This document was constantly updated by information from users, and contained verified information about the death toll, how to help, how to find more information, and where to go in Nepal for food, water, and other resources.

Kumar also talked about his latest project, launched in August, called Rahatpayo (‘did you get relief?’). This tool, on Facebook and Twitter, allows people to confirm whether or not they received relief, and whether they are injured. Kumar highlighted the idea of making data public, and the importance of transparency in social media movements. Kumar concluded his presentation with an open invitation for developers, data analysts, mappers, and marketers to join the project.

Kevin Bubriski, a professional photographer and professor at Green Mountain College, spoke next. Bubriski invited the audience to question what social media is, suggesting that things like cave paintings, religions, and music are a form of social media in their ability to spread information. He posited the notion of social media as a forum where everyone has a voice and the right to share their opinion and their story, using PhotoCircle and Photo Kathmandu as examples. Photo Kathmandu was the first international photography festival held in Nepal, with photography presented in the streets of Kathmandu for all to see for free.

Austin Lord, Dartmouth ’06, an anthropologist, visual ethnographer, and the director of Rasuwa Relief, concluded the panel. He outlined prevalent themes in his experience of social media and entrepreneurship in Nepal. He discussed the Nepal Photo Project, in which a hashtag grew into a large scale art project: Photo Kathmandu. He also described the various Facebook groups he belongs to, and how they have become a forum for sharing ideas, images, information, and memories.

Lord discussed his latest project, the Langtang Memory Project. In Nepal after the earthquakes, Lord saw firsthand the effects of social media, like Facebook groups for finding missing people, on healing communities through unity and documentation. This led him to start the Langtang Memory Project to foster community memory and remembrance. Lord’s presentation was followed by a Q&A session for the panelists. Some questions were specifically about app development, but overall Lord dominated the conversation.

Core issues:

Structure-Agency Representation

Center-Periphery Transparency

Community Memory

The panel “Social Media and Social Entrepreneurship in Response to the Earthquakes” touched upon many important issues, the first and most obvious of which is that of representation.

Social media was a primary platform by which images of and information about the earthquake and its aftermath were disseminated following the event. Social media propagated many representations of the earthquake, both from within the country and from foreign sources.

Some representations within social media were data-driven, like the Google Doc Ravi Kumar created containing verified sources of food, shelter, and water around the country. This Google Doc was an accurate and utilitarian representation of the situation on the ground in the aftermath of the earthquake. It was disseminated via social media, thus making the data open and accessible to everyone with an Internet connection.

Max Von Hippel’s app Chetawani is another example of a data-driven representation of the earthquake and its aftermath. Chetawani contained validated news stories, a curated collection of links to different resources, and the Kathmandu Living Labs Quake Map.

Kathmandu Living Labs Quakemap

Because the app and its various features operated in real time, this was a realistic representation but its period of peak utility was very limited. In the immediate aftermath of the earthquake it was very difficult to get Internet connection and therefore near impossible to access the app. Then later on, as relief and resources became more established and consistently available, the app’s utility as a crisis response tool dropped once more.

While these projects are important for increasing transparency through social media and encouraging open data, the important consideration of discrepancies in levels of access remains. Ravi Kumar’s organization Code for Nepal recognizes that there are deep inequalities in Nepal where people’s access to the Internet and digital training is concerned. Women, minorities, and people living in poverty or in rural areas – people on the peripheries of Nepali society – have severely limited access to the Internet and digital training in Nepal.

Code for Nepal – Increasing Digital Literacy

These issues of access are structural obstacles that limit people’s agency within the realm of social media as a crisis response method. Kevin Bubriski and Austin Lord touched upon the idea of social media and photography as mediums that “give voice to the voiceless,” or those without the resources to make their own stories and opinions known. But the “voiceless,” first have to gain access to these tools in order to make use of them and find a forum in which their voices can be heard.

Facebook: your emergency rescue of the future?

Bubriski and Lord also discussed social media and photography as a method of preserving history and creating community memory. Beyond the immediate implications of social media as a rapid method of communication and information distribution, this technology can also serve to archive cultural information and individual histories. Bubriski and Lord both emphasized that in Nepal’s undemocratic political climate, social media and photography, their preferred archival medium, create a kind of democracy among diverse experiences and backgrounds.

Significance

As was made clear in this panel, the advent of social media as a tool in disaster relief has drastically changed the ways people communicate and rebuild in the aftermath of disaster. The panelists offered a unique lens for understanding the Nepal earthquake through the role of social media in relief effort, and challenged popular notions of social media itself: Kevin Bubriski posited that social media includes photography, cave paintings, and music – any form of information dissemination extending beyond word of mouth.

The panelists described how social media, in all its forms, allowed people throughout Nepal and around the world to contact friends and family, call for resources and relief, and raise awareness about the extent of the destruction. The astounding relief efforts brought about by social media, even in with limited social media access, is a significant takeaway from this panel and one of the biggest lessons to come out of the Nepal earthquake. The success of social media as a tool in disaster relief in Nepal sets an important precedent for future disaster relief efforts, and encourages people to think about what could be next.

With some planning and innovation, the expansions upon these uses of social media in the aftermath of disaster could be extremely helpful in future relief efforts. Austin Lord discussed this shift of focus towards the future, and how Nepal can better prepare itself for future disasters. It would involve engaging informed Nepalis in both urban and rural regions, providing a basis for offline documentation, and equipping Nepalis with the ability to document their own experiences. This means providing both the equipment and education necessary to fully utilize and take advantage of potential social media resources.

Social media creates a forum for news and support that fosters a sense of community cohesiveness and facilitates social healing as well as physical rebuilding. In the aftermath of the earthquakes, social media has helped people rebuild their lives, homes, families and communities. As an archive of the lives lost, of the resilience of the Nepali people, and of the national effort to rebuild, social media gives people autonomy over the construction of the disaster and its aftermath in community memory and recorded history.

This panel itself, and its discussion on the effectiveness of social media as a tool for disaster response and relief, is significant in that it could have challenged audience members’ preconceived notions of the state of technology in Nepal. Himalayan areas often carry the connotations and characteristics of a “Shangri-la” in Western imagination: a place lost in time, void of influences from the outside world, giving it a mysterious and removed characteristic. Embedded in this notion are ideas of sparse technology and limited connection, both internally among villages and externally with the outside world.

The photos displayed during this panel demonstrated clearly the current technological situation in Nepal. Younger generations of Nepalis were seen holding devices, particularly smartphones, and often taking pictures of their own. In juxtaposition, older generations were more often seen praying and engaging in “traditional” practices than interacting with technology. Younger monks were also seen with devices such as iPads and mobile phones, suggestive of the fact that technology use is linked less to preference for tradition, and more with technological competence.This panel and its images and themes were therefore important for sharing with audience members the reality of Nepal’s digital landscape.

Discussion Questions

- Is there a way to “properly” or “appropriately” depict disaster? Is it possible to discriminate between sensationalist portrayals and honest representations?

- How does social media affect existing inequalities in relief distribution?

- How can social media be more effectively used as a crisis response mechanism in the future? What are the major takeaways from this panel that could be applied to the role of social media in future natural or man-made disasters?

- How do technological tools like social media platforms change internal representations of disaster? In what ways does social media and its portrayals of disaster change self representations and understandings of the events and society?

- How does a disaster impact realizations of impermanence and the introduction of projects for recording and preserving culture and history?

- What are the areas of overlap between social media and social entrepreneurship? How does each support the other?

Additional Readings and Resources

Social Media Services for Nepal Earthquake (The New York Times)

Nepal earthquake: Govt using social media to connect and provide relief (The Times of India).

Devastation in Nepal (CNN)

In Nepal, Instagram Plays Vital Role In Spreading Info To Earthquake Survivors (Huffington Post)

How One Company Used Social Networking Technology to Respond to Nepal’s Devastating Earthquake (Business Insider)

How social media is helping Nepal rebuild after two big earthquakes (Quarz)

Nepal earthquake: How open data and social media helped the Nepalese to help themselves (ABC)

Nepal earthquake: how social media has been used in the aftermath (Social Media for Development)

#SocialMedia and #BigData: Significant Role in Nepal’s Earthquake Relief Efforts (NewzSocial)