ABSTRACT: On Feb. 18th, 2016, the Nepal Earthquake Summit at Dartmouth College discussed the work of photojournalists Kevin Bubriski and James Nachtwey through a panel entitled “Representing Disaster” at the Hood Museum of Art. Nachtwey flew into Nepal three days after the April 25th, 2015 earthquake, while Bubriski arrived in Nepal five weeks after the devastation struck. Moderator Katherine Hart from the Hood Museum led the panel, which began with presentations from the two photographers and then continued into a question and answer session. The panel navigated topics such as the duty of photojournalists as first responders, visual documentation as a means of immediate communication to a mass audience, the relationship between photographers and their subjects, the position of social media in natural disasters, and the role of photographers in the midst of tragedy. Various themes emerged, such as the resilience of Nepali citizens, ethical considerations regarding representation, and the power of visual media to spread awareness and bring about change in disaster situations.

BACKGROUND & HISTORICAL CONTEXT

All statistics and figures cited from Emspak 2015 (see bibliography).

The devastating 7.3 magnitude earthquake that shook Nepal on April 25th, 2015 took the lives of more than 9,000 people, while injuring some 23,000 more. In total, an estimated 4.6 million people in the region were exposed to tremors from the Nepal earthquake. Thirty out of 75 Nepal districts were affected by the quake. Hundreds of thousands were left homeless as entire cities and villages were reduced to rubble. It was the worst earthquake in Nepal in more than 80 years, nearly matching the death and destruction of the 8.1 magnitude quake near Mt. Everest in 1934. Since the catastrophic event, the Nepali’s have made a concerted effort to rebuild their lives, starting with their homes and communities; however, resources are limited and a current political stagnation with India has limited workers and supplies even more.

“Inhabitants salvage building materials from their destroyed homes in Gumda Village, near the epicenter of the earthquake in Gorkha district, where five people died and 14 are still missing in landslides, May 8, 2015.” Photo and caption by James Nachtwey, TIME Magazine, May 15, 2015.

This past month from February 18th to 20th, Dartmouth College hosted a summit on the reconstruction of Nepal after the 2015 earthquake. Professors, students, photographers, residents, doctors and more gathered to discuss and present their research surrounding the earthquake and its effects on the Nepali physical and cultural landscape today. The aim of the summit was to generate awareness and meaningful discussion surrounding the current situation in Nepal, post-earthquake. A diverse group of experts on the event directed the conferences, presenting on their work in quake-affected regions. On Thursday, February 18th, two renowned photojournalists took the stage and commenced the 2016 Dartmouth Earthquake Summit.

Just three days after the earthquake devastated the Gorkha District of Nepal, photojournalist James Nachtwey captured the aftermath of the distraught center and periphery of Nepal through his camera lens. A short five weeks later, fellow photojournalist Kevin Bubriski flew to Kathmandu and captured the resilience of the Nepalese people and the rejuvenation of a city that was covered in rubble. Nachtwey, winner of two World Press Photo awards (among several others), and Bubriski, with extensive work in Nepal since the mid 1970’s, offered powerful presentations on their efforts to document the gripping event and its aftermath.

THE PHOTOJOURNALISTS

James Nachtwey, part of the Dartmouth Class of 1970, grew up in Massachusetts. Nachtwey first considered becoming a photographer when he was moved by formidable images from the Vietnam War and the American civil rights movement. Nachtwey’s photojournalism career began in 1976 when he began working at a newspaper in New Mexico. Shortly thereafter, he relocated to New York to follow his dream to be a freelance magazine photojournalist. Nachtwey has devoted his life’s work to documenting wars, engagements, and tensions across the globe. The countries in which he has worked are numerous, from Gaza and the West Bank to Afghanistan and Rwanda. Through his work as a photographer, Nachtwey has won countless honors and awards — namely, the Martin Luther King Award, Magazine Photographer of the Year award seven times, and the International Center of Photography Infinity Award three times.

Kevin Bubriski was born in Massachusetts and graduated from Bowdoin College in 1975. Following his graduation, Bubriski joined the Peace Corps and went to Nepal to one of the most severely economically despondent regions in the world. He has worked as a photojournalist in many corners of the world, including India, Tibet and Bangladesh, and spent nine years photographing Nepal. His works are currently exhibited in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art and the Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris. Bubriski, who has received the prestigious Guggenheim, Fulbright and NEA fellowships, is one of the most recognized photographers in this day and age. He is currently a professor at Green Mountain College in Vermont.

EVENT ETHNOGRAPHY

The event began with an introduction by Daniel Benjamin, the Director of Dartmouth’s John Sloan Dickey Center for International Understanding. He stated the symposium’s goals of fostering international understanding, before professor and event organizer Ken Bauer and Hood Museum head curator Katherine Hart introduced the two photojournalists and the panel itself. The panel consisted of two presentations by each photographer, then a question and answer session.

The room’s demographics were roughly as follows. Regarding age: ⅓ elder (defined as having white or gray hair), ⅓ middle-aged (appearing to be in their 30s-50s), and ⅓ young adults (appearing to be in their 18-20s). Many young adults are university students; this is influenced by the mandatory presence of a group project from Anthropology 32. There were a few young children, all Caucasian — likely professor’s children. Regarding gender: ⅔ male, ⅓ female. Regarding race and ethnicity: 90-95% were Caucasian, which is defined here as white or, alternatively, white-passing. The few non-white attendees seem to be Nepali. The spatial distribution of the demography is fairly equal by age and gender. However, the few non-Caucasian individuals present tended to group together and sit more to the side of rows. Most audience members attending are dressed in nice-casual clothing — lots of sweaters, sports jackets, button-ups. The younger one is, the more casually dressed one is; for example, at least two students were both wearing sweatshirts and jeans. Do the demographics of the panel reflect Hanover, the discomfort with this kind of voyeurism people of color may feel, or some degree of both?

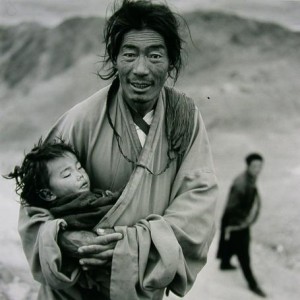

“Pilgrims on the Ling Khor Ganden, Tibet, 1994, silver gelatin print.” Photo and caption by Kevin Bubriski.

The struggle of positionality and representation on the photographers’ end when documenting the earthquake was a very present, underlying theme throughout the panel. For James Nachtwey’s speech, he often read word-for-word from his May 8, 2015 TIME Magazine article entitled “James Nachtwey’s Dispatches from Nepal.” This speech was at times embedded with an Orientalization of Nepal and the Nepali people, similar to Lionel Caplan’s article on Gurkha soldiers, “Bravest of the Brave: Representations of ‘the Gurkha’ in British Military Writings.” (Caplan 1991; see also, Said 1978). For example, he described that he had previously desired to visit Nepal, “not so much as a journalist, but to see the mountains and the temples,” and he described the identities of Nepalis as being “forged in hardship and closeness to nature” and as being known for their “strength and self-reliance, their equanimity, friendliness and spirituality” (Nachtwey 2015).

Despite these touches of Orientalism, however, Nachtwey impressed the audience by acknowledging his genuine disposition as a photographer to wholly capture the stories of his subjects, noting that there are always “physical and emotional boundaries” between him and his subjects. He was very aware of his positionality, and did not fail to mention that as a war, conflict, and critical issues photojournalist, he is acutely aware of his inadequacy — even going so far as to say that he “cannot do justice” to what his “distressed and silenced” subjects are going through.

“Photographer Kevin Bubriski’s work in the aftermath of the earthquake in Nepal is featured in “The 2015 Nepal Earthquake,” an exhibit at the Hood Museum of Art in Hanover, N.H., from January 23, 2016, to March 13, 2016.” Caption by the Valley News, “Dartmouth to Host Nepal Aid Summit,” Jan. 25, 2016.

The decision to bring in Nachtwey and Bubriski together to observe the differences in their photojournalism of the earthquake effectively painted a fuller picture of the earthquake due to the juxtaposition between Nachtwey’s documentation of the immediate trauma of the event versus Bubriski’s documentation of the ongoing reconstruction process happening five weeks later. The mood of the two photographers’ work was extremely different. Nachtwey’s photography gave testimony to a very tragic and disastrous moment in time, many of the subjects of his photos in tears and expressing extreme anguish amongst a backdrop of total destruction — the main subject matters were destroyed homes, piles of rubble, families in mourning, and confusion and desperation. On the other hand, Bubriski’s photos had a drastically different tone. His subjects had the look of hope on their faces, a few of them smiling. His images captured people picking up the pieces of the rubble to reconstruct the villages and urban spaces that had been destroyed. Ultimately, he said “life had gone back to normal,” as he documented instances such as a young Nepali girl walking through the rubble on her way to and from school. It is typical to witness the media intensely covering the initial impact and shock of a natural disaster. But then, after a few days of intense coverage, the cameras leave and the world turns its attention to the next new thing — leaving the affected people and the journey of reconstruction behind and forgotten. Bubriski’s photojournalism brought the camera back to the region, however, and gave a strong testimony to the normally overlooked, long-term process of reconstruction. Both photographers offered very different, yet important and informative, lenses to the disaster.

This panel was informatively communicated the role photographers play in disaster-type scenarios. Both Nachtwey and Bubriski made it very clear that their jobs as photojournalists are simply to act as first responders and to effectively communicate information through their photos, devoid of an agenda of artistic expression. Naturally, ethics are a very important focus, but Nachtwey made clear that “high quality communication to a mass audience is the goal, not making art” and that “journalism is a testimony.” Bubriski said that the job of the photojournalist is to “report facts with a trained eye” and to “deliver what is real,” with as little editorializing as possible. The power of photography to communicate information rapidly and eventually effect change was a very vital theme of the panel.

CORE ISSUES

“Bodies are prepared for cremation during a Hindu ritual at the Pashupatinath Temple in Kathmandu on April 28, 2015, three days after a 7.8 magnitude earthquake devastated Nepal, killing at least 7,000 people and causing untold damage.” Photo and caption by James Nachtwey, TIME Magazine, May 8, 2015.

In addition to honoring the powerful work of the photographers, this panel raised a series of difficult issues. Some of the most salient emergent themes were: the duty of a photojournalist as an emergency first responder; the ethical considerations of documenting another’s tragedy; and the intersection between art, social media, and natural disasters. Both photographers touched on views of their roles as photojournalists in an emergency situation, and described the complexities of taking on this role. Nachtwey conveyed a sense of responsibility as a first responder to get images out into the global view as quickly as possible in order to raise awareness and mobilize aid. He explained that he saw his work in Nepal, specifically with the International Rescue Mission, as “an ally to NGO work.” In this case, the purpose of photojournalism becomes that of impartial first response reporting to affect change.

However, Nachtwey also emphasized the difficulty of documenting another’s distress and the emotional obstacles that arise both for the subject and the photographer. The photographer must navigate the struggle between balancing emotional responses with professional duties. As an outsider, it is crucial to be mindful of cultural contexts and of one’s own positionality. Nachtwey stressed the importance of respecting the people above all else and gaining their permission before proceeding. He reported, “I have always felt an inadequacy because a photo can’t fully capture what these people are enduring… I don’t think I can even do justice to what they’re going through. I can only do my best.” With this statement, he acknowledged his own positionality and the limitations of his work. Bubriski conveyed the same sense of humility, and he expressed the need to maintain integrity and authenticity in his work by not altering his photographs via photo editing programs. Both expressed that they saw their work in this situation primarily as tools to bring about change rather than ‘art’ for t he sake of aesthetics.

he sake of aesthetics.

A major theme that arose was the ethical consideration of documenting someone else’s tragedy, and the fine line between photojournalism and voyeurism. As mentioned previously, both photographers stressed the need for sensitive communication with their subjects. Additionally, another point brought up was how, in order to represent a crisis such as the Nepal earthquake respectfully, the photojournalist must be thoughtful about how they choose to publish their materials and display them to a greater audience. Both photographers explained that they take care to collaborate only with organizations and publishers that they trust to use honest work ethics and to represent issues with authenticity.

SIGNIFICANCE

Photography spreads awareness to mass audiences and creates exposure for important issues more quickly and effectively than most other mediums. The explosion of communication channels in the 21st century has only made photography and photojournalism more relevant and more significant as a tool for reporting events around the world. The exposure photojournalism brings can lead to direct and concrete change — most financial aid after the earthquake came from outside sources, who were aware of the devastation through its representations in the mass media.

“Bishnu Gurung sobs after her 3-year-old daughter, Rejina Gurung, was found buried in the rubble in the village of Gumda in Gorkha district, near the epicenter of last month’s Nepal earthquake, on May 8, 2015. The baby’s father is a guest worker in Malaysia.” Photo and caption by James Nachtwey, TIME Magazine, May 8, 2015.

However, like all tools, photography must be analyzed in order for it to be an effective tool for change. “Representing Disaster” discussed several issues wrapped up in modern photojournalism, and did so from the mouths of professionals who have been working in the field for decades. We live in a time where photos plaster computer screens, television screens, magazines, and every other conceivable form of visual media. We must be critical of what we see in order to fully understand what we’re seeing and shy away from false assumptions, stereotypes, and other subtle misconceptions found at the surface of photography. While photojournalists such as Nachtwey may describe themselves as an “impartial first responder,” visual media always belies hidden (or obvious) biases — what one chooses to represent, how one chooses to represent it, and the publications or channels to which photographs are distributed, all change how audience’s interpretations and understandings of both a photograph and the events it depicts.

Despite photojournalism’s limitations, it is undeniably an important and useful tool for comprehension and analysis. For example, this panel was important for understanding the earthquake because it quite literally showed the devastation — we have a perspective into not only what happened, but also what it actually looked like. Bubriski’s and Nachtwey’s photography communicates the earthquake through poignant visual documentation, leading to better and fuller understandings of the earthquake and its consequences. At its core, photojournalism creates lasting visual testimonies.

Stepping back, “Representing Disaster” was also important as a lens through which we can understand Nepal at large. As discussed earlier, Bubriski’s and Nachtwey’s work brought up issues of Western positionality in regard to representing non-Western cultures, respect for others’ grief and emotional state of being, and the role that visual media can play in mobilizing global awareness and change. These issues illustrate and illuminate the complexities of modern Nepal, and the lives of those who live within its borders.

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

- Where do you draw the line between real storytelling and artistic liberty? Where should we distinguish between telling a true compelling narrative through visuals, and painting pictures for people with photos?

- How does the race or ethnicity of a photojournalist impact their work in various communities? Is the work of Western photojournalists in Nepal and in other non-Western countries inherently Orientalist or voyeuristic on some level? Why or why not?

- Bubriski and Nachtwey claimed during the panel that photo editing is unethical, however, many publications use photo editing when presenting their photojournalism to the mass media. Where do you draw this ethical line? Is altering photos when covering conflict or disaster ultimately unethical?

- Photojournalists convey their message through an image. Unlike a writer, they cannot include a disclaimer such as “my collection of images only represented the periphery of society.” Also, the observer can interpret an image in many cases. How might these issues change the perception of what a photojournalist has captured?

ADDITIONAL READINGS & RESOURCES:

If you would like to learn more about Bubriski and Nachtwey’s work, please visit their professional websites by clicking on their names. You can also visit TIME articles from May 15, 2015 or May 8, 2015 on Nachtwey’s work in Nepal. To learn more about James Nachtwey as a war photojournalist, listen to his enthralling TED talk, seen earlier in this article. Further photography regarding the earthquake by various photojournalists can be found online at the New York Times. For further discussions on Orientalism and how it influences visual media, check out a copy of Orientalism by Edward Said at your local library, or purchase it online through Amazon. Alternatively, you can read a critical essay by Matthew Scott regarding Said’s Orientalism in the Oxford Journal “Essays in Criticism” here.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bubriski, Kevin and James Nachtwey. “Representing Disaster.” Dartmouth Nepal Earthquake Summit. Feb. 18, 2016.

Caplan, Lionel. “’Bravest of the Brave’: Representations of ‘the Gurkha’ in British Military Writings.” Modern Asian Studies 25.3 (1991): 571–597. Web.

Emspak, Jesse. “Nepal Quake Could Have Been Much Deadlier, Scientists Say.” LiveScience. TechMedia Network, 6 Aug. 2015. Web.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Vintage, 1978. Print.

Wolfe, Rob. “Dartmouth to Host Nepal Aid Summit.” Valley News. 25 Jan. 2016. Web.