Does the Art Belong to the Artist Anymore?

Censorship of Public Art in Northern California

What America was founded on and is the very basis of this country is freedom, especially the freedom of expression. Although we are allowed to talk freely about our dreams or practice our religions, the government still tends to suppress unfavorable ideas. Even in the form of creative expression, art, the U.S. government and those with power and money have the strength to choose which art is released to the public and which are to be destroyed. When Mexican muralists, such as Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco, were commissioned in the U.S., their works were heavily criticized, some eventually destroyed, for their radical and blunt illustrations of politics and Mexican and American culture. However, back in Mexico, these artists’ murals were freely presented to the public; even sacrilegious and communist images were painted in churches and schools. For example, Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads, which was controversial for its depiction of Lenin and Rivera’s support for the Soviet Union, was destroyed at the Rockefeller Center in New York City but preserved at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City. The question of America’s hypocritical nature, pursuing freedom yet censoring the voices of some, during this time can be answered by the unstable economic state of the country during this period, where the nation’s strong nationalistic, democratic, capitalist foundations felt threatened by the Great Depression and by the rise of communism from around the world. Today, we can see the continuation of censorship of art. I will be analyzing the public art I have seen near my hometown of San Jose, California, in the cities of Palo Alto and San Francisco, to show how the socioeconomic states of each area heavily influences the type of art being acceptable in the community. In Palo Alto, the area is much more private, upper class and in San Francisco, the area is more public and socioeconomically diverse, and the art being displayed in each area reflects the amount of control the government or artist has over his or her own art, the types of people living there, and the access to the public walls that the local artists have for their works of public art.

The history of censorship of public art in the U.S. started with Los Tres Grandes, when Rivera and Siqueiros’s works were rejected by the upper crust of society.

Figure 1

In 1931, Rockefeller commissioned Rivera to paint a mural that followed the title of Man at the Crossroads Looking with Hope and High Vision to the Choosing of a New and Better Future (Figure 1) at the Rockefeller Center in New York City (Rochfort 130). Rivera assured that he would follow the prompt but left out one very important detail: the figure of Vladimir Lenin would feature prominently in the design of the mural (Rochfort 132). Previously, Rivera’s work in San Francisco and Detroit did not feature the communist movement (Rochfort 131).

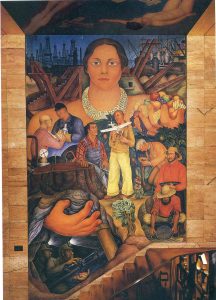

Figure 2

In San Francisco, Rivera painted Allegory of California (Figure 2), a very positive depiction of his excitement and hope to be in this “modern industrialized country” (Rochfort 124). The mural is centered on the tennis star, Helen Wills Moody, who depicts Rivera’s image of “richness, gold, petroleum, and fruits” (Rochfort 124). She is surrounded by the themes of “transportation, rail and marine…energy and speed,” further emphasizing Rivera’s fascination with the industrialized city (Rochfort 124). Compared to some of his other politically charged murals, such as Man at the Crossroads (Figure 1), where he exalts communism, or Wall Street Banquet, where he critiques capitalism, this mural in San Francisco is extremely positive, with no criticism of American society, politics, or economics (Rochfort 124). However, artists, mainly Siqueiros, criticized Rivera for not being communist enough, especially since Rivera took many commissions, an act that seemed very capitalist (Rochfort 131). In the end, when Rockefeller found out Rivera had painted, he promptly asked Rivera to leave and destroyed his work (Rochfort 132). Rivera’s idea of “political and social transformations of the modern industrial age” differed from Rockefeller and the U.S.’s definition (Rochfort 132). Communism was a highly controversial topic, one looked unfavorable upon, and this subject was prohibited in artwork in the capitalist United States, as seen by Rockefeller’s reaction to Rivera’s work. When Rivera returned home, he painted Man at the Crossroads (Figure 1) at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, where the mural still stands today (Rochfort 133). This contrast in preservation versus destruction highlights America’s freedom of expression of only ideas that support the construct of the country while showing the true freedom of expression in Mexico, where controversial ideas are allowed and presented to the public. In America, it is shown here that art is heavily controlled by the upper class; while, the artist has the freedom to create, he or she does not have the freedom to choose what is shown to the public. In Mexico, the art always belongs to the artist; it is the artist who creates and also gets to choose what he or she wants to display.

Figure 3

In Los Angeles, Siqueiros faced similar criticism and consequences over his controversial work. In 1932, F. K. Ferenz, director of the Plaza Art Center gallery, requested that Siqueiros paint a mural on the roof of the Italian Hall, where the Plaza Art Center gallery was located, in Olvera Street, where a high concentration of Mexicans lived (Rochfort 146, Martínez). Siqueiros painted América Tropical (Figure 3), which was a mural that focused on a controversial image. At the center, the mural depicted “‘as a symbol of the United States’ imperialism, the principal capitalist oppressor…an Indian crucified on a double cross, on top of which stood the Yankee eagle of American finance,’” a direct attack at the way America unfairly suppresses the Mexican population (Rochfort 146). However, this message was not received well by the owner of the wall and Christine Sterling, the primary contributor and renovator of Olvera Street, and the mural was eventually whitewashed (Martínez). Siqueiros’s view of America’s reality differed from Ferenz and Sterling’s, and this unwillingness to acknowledge America as the oppressor and the problems going on in California during this time caused this piece of work to be covered up during that time. Although the surrounding area had a large Mexican population, the curator of the street, Sterling, was white, and she created the street with an idealization of Mexican culture (Martínez). In this case, she was the one with the power to choose what was represented on the wall and did not like the contrast between Siqueiros’s reality and her “whitewashed”, idealization (Martínez). In both situations, those with power and authority, ownership of the walls could not stomach the truth, the reality of the way things are, whether it is internationally or domestically. Continually, the people of America, especially those with money and power, chooses to focus on the good and avoid the reality, as they enjoy the way things are right now. Rivera and Siqueiros’s works are renown and provocative because of their depictions of the brutal truth and their core values, but because of these illustrations of the uncomfortable, controversial reality and truth, their art is rejected from the United States.

Likewise this trend of censorship continues, with Los Tres Grandes directly influencing the art being displayed and created in Northern California, especially San Francisco, where Rivera created several murals. Rivera’s presence in San Francisco “marked the beginnings of a debate about the complex relationship between murals, the left, and the public” (Lee xix). His controversial work attracted attention from fellow artists and critics and to the issues of “ethnic minorities and the working class” (Lee xix). Rivera’s work influenced the controversial and not idealized concepts of the San Francisco painters’ works, such as during the New Deal projects and private mural commissions from 1931 and onward (Lee xix). Even in contemporary times, the influences of Rivera and the other Mexican muralists are present. For example, the city’s murals still often display politically charged images, such as issues with Civil Rights, women’s rights, education, and the Vietnam War in the 1960s, and the struggles of the colored and working class (Drescher 12).

During this time, San Francisco mural art also began to embody the idea of community art, where art is “created by or with a group of people who will interact with the finished artwork” instead of the broader public art where art is “done for a general, undefined population” (Drescher 12). Community art became an important aspect in the city as its relationship to the community is “dynamic, intimate, extended and reciprocal” with its “intersection of social and artistic contexts” (Drescher 13). This is to say that the mural art of some locations in San Francisco, such as the Mission District, is tailored to its specific community, with the artist drawing for the community and the community keeping the art alive by supporting and accepting it (Drescher 12, 13). This remains alive today in Clarion Alley in the Mission District of San Francisco, where the art presents issues that the artists themselves, who are from the community. and those from the community face each and every day. These issues, such as poverty or the housing crisis, are personal issues to the area and would not be able to be replicated or receive the same response elsewhere. However, in the city of Palo Alto, over an hour south of San Francisco, the art does not reflect the idea of community art as much. This is because the government heavily regulates the art. Although the artwork, sometimes even made by children in the community, depicts the happy, sunny lifestyle found in the city, it is much less piercing and personal. I believe that the artwork in Palo Alto could be replicated in other Californian communities, showing that these works are not personal to its community. This broad, vague ideas presented in the Palo Alto murals are a result of the censorship of art in this city.

Further explained, in Palo Alto, art is heavily regulated by the government and influenced by the culture dominated by educated, upper class citizens. One artist that is celebrated by the city is Greg Brown, who passed away in 2014, who has been creating public art in Palo Alto since 1975 (Sheyner). He was hired by the City of Palo Alto that year and painted Pedestrian Series (Figure 5) the next year at University Avenue in downtown Palo Alto, near Stanford University (Sheyner).

Figure 6

Selected Works from Pedestrian Series, University Avenue, Palo Alto, California

Figure 5

This series depict everyday activities, such as residents taking a stroll or taking out the trash, in a fun and fanciful manner. His “realistic and often whimsical depictions of crooks, aliens, cunning animals and everyday people” are seemingly normal and blend in easily with the street (Sheyner). I have experienced this first hand as this is a street that I frequent often, whether it is for a college interview at Blue Bottle Coffee or in search of a lunch spot at the newly opened Lemonade. Despite the countless walks I have had up and down the streets, it was not until this past winter break that I first noticed Spiro Pushing Pet (Figure 6), a part of the Pedestrian Series (Figure 5). My lack of awareness of the presence of this artwork further emphasizes the point that his art easily blends into the city. His artwork is simple and straightforward and has been “amusing local pedestrians for nearly four decades” (Sheyner). Unlike the Mexican muralists, Brown’s art did not challenge or provoke or make society feel uncomfortable, despite the humorous additions of robbers climbing walls or aliens as pets. Another reason for his safe and harmless work is the fact that the city government and city’s art commission are supporting his art. The government, especially the Palo Alto Public Art Program and Public Art Commission, must approve his work and ideas before he can take the next step and create the art (City of Palo Alto).

Another artist, Mohamed Soumah paints similarly in Under the Sun (Figure 7), a mural on California Avenue, another downtown and lively street, in Palo Alto. Like Brown, Soumah worked with the Palo Alto Public Art Commission to get his first work in America commissioned and approved by the city to paint on the Country Sun Natural Foods store (Thorp).

Figure 7

This mural on the back of the store depicts the overflowing sunshine peeking through the clouds, overlooking the grand hills and hundreds of bright California poppies (Figure 7). The mural gives an extremely positive depiction of and exalts California, similar to Rivera’s Allegory of California (Figure 2), yet another example of a mural in Palo Alto that serves a decorative purpose to the city versus a strong message that is often seen in Los Tres Grandes’ works. While Siqueiros and Rivera also needed to receive approval from a higher level, they never had to fully flesh out their ideas for them and ended up freely painting some of their controversial ideas. In both Brown and Soumah’s work, the work went through intense approval and had positive depictions of and effects on the city; the city of Palo Alto only “promotes the highest caliber of artwork” that celebrates “Palo Alto’s character…civic pride and sense of place” (City of Palo Alto). Their work did not and was not allowed to evoke strong or opposing opinions. I believe this contrasts the Mexican muralists’ works, especially Siqueiros’ América Tropical (Figure 3) and Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads (Figure 1), and this is because of the culture of Palo Alto, as seen by the city’s requirement for its art. The majority of those that live in Palo Alto are educated and middle to upper class citizens. The type of people that inhabit the area is influenced by the presence of several prestigious schools in the city, Stanford University and Palo Alto and Gunn High Schools, and the large number of innovative companies in these areas, such as investment banking firms or SurveyMonkey. The presence of higher education, high tech work, and a family friendly environment attracts many families to this safe, stable area. The secure and comfortable feel of the city leads the permanent art of the city to have the same calming vibe; it is uncommon to see something extremely disturbing or provoking in this city. I believe this is also why a panel approves most of the public art in the city: to preserve the stable nature and status quo of Palo Alto. In this way, while protecting its citizens, Palo Alto also censors certain types of art. Because of this censorship, the art in Palo Alto belongs to the city instead of the artist. While in Mexico, the artists could paint anything they wanted to, in Palo Alto, the artists are restricted by the requirements of the city. Art that has negative connotations, threaten the city’s ideals, or have the potential to strike up a revolution would not be found in this city.

This type of provocative street art can be found in San Francisco, however, where the culturally and economically diverse population allows for streets like Clarion Alley to exist and where temporary art targeting the problems of the city is freely drawn. Many of the artists who paint in Clarion Alley are part of the Clarion Alley Mural Project (CAMP) where they use their art to promote movements, change, and justice in the community (Clarion Alley Mural Project). “In a city that is rapidly changing to cater to the one-percent at every level,” the non-profit CAMP serves as a contrast to this with its support coming from dedicated artist and other community members (Wilson). CAMP even discourages commercialization, deterring large tour groups and real estate corporations in the Mission District from exploiting the alley for profit (Wilson). When I visited the alley two years ago, I personally felt they achieved this goal because the alley felt like it was hidden. There were a good number of tourists, but it was individual groups coming to enjoy the art in a serene manner, not huge, rowdy tour groups crowding the street. In this way, CAMP supports its artist, some who have been displaced by the increasing price of rent, by fighting against this structure and supporting a space to express their thoughts on “social, economic, and environmental justice” by advocating for new ideas and inclusiveness (Wilson). While in Palo Alto, the murals are commissioned by the city and the city council has to approve of all the public art before it is drawn, in Clarion Alley, no one is forcing or prohibiting the artists to make their work, so the art truly belongs to the artists themselves. I believe that this is because the location of San Francisco tends to be viewed as more diverse culturally compared to the stable status quo of Palo Alto. The location of the murals is an abandoned alley, a small, hidden strip of pure art. The work is also being constantly replaced, and every time I go to Clarion Alley, the alley looks different and there is a new panel to reflect a new issue being highlighted. This casual, temporary feeling completely contrasts that of Palo Alto. The clean, safe, prepared street art of Palo Alto reflects their structured way of life, while the fleeting, controversial work in all corners of San Francisco reflect a more tumultuous life, with dissent towards politics and economics and many who live unstable lives. In this way, the messiness of San Francisco life allows for the infiltration of art with messier messages. We can also see more poverty and homelessness in San Francisco than in Palo Alto, but we can also find shopping areas in Union Square and business in the Financial District in the very same city. The contrast of the city is reflected in the outspokenness of the people about their dissatisfaction or their liberal views with the common occurrences of protests and movements, such as the Pride Parade. Clarion Alley and the artwork in it truly reflect the unstructured, spontaneous, loud style of the city, stemming from Rivera’s first appearance in San Francisco. As mentioned earlier, his first works in the city exposed the artists of the city to his controversial works and pushed them to be not afraid to express these ideas.

Megan Wilson, an artist on Clarion Alley in San Francisco and one of the Clarion Alley Mural Project’s core directors, has had several of her bold, vibrant murals, which focus on issues with the wealth gap, featured in the alley. Her works focuses on the idea of home and homelessness and directly reflect the goals of CAMP by explicitly calling out the issues with capitalism and the one percent.

Figure 8

For example, in her piece Tax the Rich (Figure 8), the very title of the piece, written in bold, black letters is the center of the work. Bright colors and large, multicolored flowers surround the words, and the color scheme is focused on the complementary colors blue and orange. The flowers overlap each other and spill onto the ground, where a happy face is at the center of the flowers on the ground.

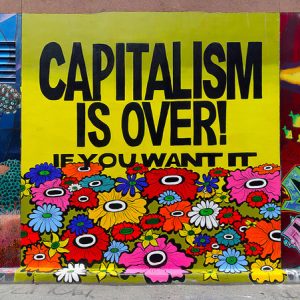

Figure 9

Another mural that looks similar to Tax the Rich (Figure 8) is CAPITALISM IS OVER! (Figure 9). This piece was created as part of the movement Capitalism Is Over! If You Want It, whose goal is to make known the negative consequences of capitalism (Wilson). Like Tax the Rich (Figure 8), the main focus of the piece is the bold black letters “Capitalism Is Over! If You Want It” against a yellow background. The bottom half of the piece is the cascade of colorful flowers that encroach on the sidewalk. The color scheme for this work is still extremely bright, but the main focus is the intense yellow. The lively, playful feelings of both murals illustrate the power of public art as this allows the murals to be accessible and applicable to all ages, even children, and seem harmless. However, the reason this mural may not be accepted in a different, more conservative community is the black, dark words at the core of each painting. These words leave no room for interpretation; the words “Tax the Rich” and “Capitalism Is Over! If You Want It” directly target the oppressive capitalist society. I believe these words and murals are also calls for action, as they are public art forms, are easily understandable, and leave no room for interpretation. Ultimately, the targeting of the public is saying the people of the community have the ability to change this current imbalance in wealth. This truly reflects the nature of the city of San Francisco. It is a city that promotes change, fast-paced and exciting, with the constant buzz of activities, whether it is a music festival or the next protest. The murals are like a protest, the raw, uncensored opinions of the community. This is completely different from the art in Palo Alto. Because it is still commissioned by the city, it is like the art in Palo Alto comes from the city, not solely from the artist. However, San Francisco truly supports its artists by not enforcing any restrictions on them. This allows the art from the artist to come only from the artists, without any outside voices. This is the reason for the existence of community art in San Francisco. The art can come purely from the artist’s voice, and this allows each artist to make art for a particular community, allowing there to be a bond directly between the artist, his or her art, and the community. In Palo Alto, the government and different committees block this bond by inserting far too many restrictions.

The public art that I have considered in this investigation is not a comparison of two separate countries, but two cities in California that are in close proximity to one another, and that I have visited frequently, and the art that is chosen to be displayed or censored is determined by each city’s culture and way of life. Through the cities of Palo Alto and San Francisco, we can see the censorship of art comes from the city government and reflects the type of city the higher officials hope to build. In Palo Alto, which is a rich suburban area, the emphasis on safety, family, and stability can be seen in the permanent, positive, playful murals on University Avenue and California Avenue. In comparison, in San Francisco, where there are more blatant instances of poverty and busy, dirty city streets are presented in the bursts of murals on any wall in the city, and many of these murals are painted with a message to support democracy, stop poverty, or criticize the government. The contrast between the two cities can be seen just in the street art as it is a reflection of the overall vibe of the city and its residents.

Annotated Bibliography

"Clarion Alley Mural Project." Clarion Alley Mural Project. Web. 07 Feb. 2017. <http://clarionalleymuralproject.org/>.

This is the main webpage for the Clarion Alley Mural Project. The website gives information about the overarching mission of this project, pictures of the murals being displayed and that have been displayed in the past, and information about the history of the project and the alley. I used this website to find art displayed during the time I visited the alley and find out more information about the various artists and their missions.

"Clarion Alley Mural Project." Megan Wilson. Megan Wilson, Web. 07 Feb. 2017. <http://www.meganwilson.com/related/clarion.php>.

This page focuses on one specific muralist, Megan Wilson, and her art in Clarion Alley. This article is useful in giving more insight on one specific artist and her work in the alley, but it also provides more information about the alley and the Clarion Alley Mural Project as a whole, including a discussion on some of the social goals of the project. I used Wilson’s website as my primary source of information about the goals and social movements of the Clarion Alley Mural Project. I also used her website for more background on her artwork about taxing the rich.

Drescher, Timothy W. San Francisco Murals: Community Creates Its Muse, 1914-1990. St. Paul: Pogo, 1991. Print.

This book discusses the history of public art in San Francisco and the motivation and purpose behind the art, usually for political and social movements. It includes the history as well as photographs of various public art around all the districts of San Francisco. I used this source to find out more about Rivera’s influence in San Francisco, the New Deal murals that were influenced by him, and the growing presence of community art versus just public art.

Lee, Anthony W. Painting on the Left: Diego Rivera, Radical Politics, and San Francisco's Public Murals. Berkeley, Calif.: U of California, 2009. Print.

This book primarily focuses on the different murals and public art in San Francisco. Not only did I use this book to analyze the motives and background of public art in the city, I also used this to gather more information about Rivera’s work during his time in the city. I used this book to expand on Rivera’s initial influence and the idea of his continued Riveraesque influence.

Martínez, Rubén. "Op-Eds Bringing ‘América Tropical’ Back to Life." Rubén Martínez. Los Angeles Times, 19 Sept. 2010. Web. <http://rubenmartinez.la/writing/op-eds/bringing-america-tropical-back-to-life/>.

This article talks about Martínez’s involvement in Olvera Street and gives background about Siqueiros’s América Tropical, including the story of how it was whitewashed and eventually restored in more recent times. I used this source to gain more insight on the conflict between Siqueiros and Christine Sterling, the owner of the street.

"Public Art Program." City of Palo Alto. City of Palo Alto, 04 Feb. 2017. Web. 06 Feb. 2017. <http://www.cityofpaloalto.org/gov/depts/csd/public_art/default.asp>.

This is the official website for the city of Palo Alto, which has a strong arts program. This page is published by the city and the city hall and is an extremely up date source that gives background about the arts program in the city as well as some of the goals for art in the city. I used this website to find out the goals of the arts program and commission and what type of art they were looking for their city.

Rochfort, Desmond. Mexican Muralists: Orozco, Rivera, Siqueiros. San Francisco: Chronicle, 1998. Print.

As we have been reading throughout class, Rochfort provides a good description of the works of each of the Los Tres Grandes, including background information, preparation of the mural, and audience reaction. In Rochfort’s textbook, I will focus on the passages on Rivera and Siqueiros in the United States. I used this book for all the background information on Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads and Allegory of California and Siqueiros’s América Tropical.

Sheyner, Gennady. "Palo Alto's Popular Muralist Greg Brown Dies." Palo Alto Online. Palo Alto Online, 02 Sept. 2014. Web. <http://www.paloaltoonline.com/news/2014/09/02/palo-altos-popular-muralist-greg-brown-dies>.

This article gives good context not only on the artist but also on the city of Palo Alto. The article discusses Brown and his death and looks back on his work in the city. It provides background on his life and work, about how it’s playful and joking nature is out of the ordinary but also widely accepted in society. I used this for more background information on Brown, the influence for his work, how he had to go through the city for approval, and the names of some particular works he did.

Thorp, Victoria. "Art All around Us: “Under the Sun” on California Avenue." Palo Alto Pulse. PaloAltoPulse.com, 21 July 2015. Web. 06 Feb. 2017.<http://www.paloaltopulse.com/2015/07/21/art-all-around-us-under-the-sun-on-california-avenue/>.

This article, written by the founder and editor of the paper and resident of Palo Alto, talks about one specific mural on California Avenue in Palo Alto, “Under the Sun”. The article discusses the process in which the mural idea was conceived, and the background of the African American painter who is the artist behind this sunny image of California. I used this work for background on “Under the Sun” and Mohamed Soumah, the artist.