“Telescoping Places”

We shall give you a gossiping personal letter occasionally, but a tour for health will not cheat its purpose with writing the oft repeated story of foreign travel.

—Samuel Bowles, from a letter printed in the Springfield Republican, May 10th, 1862

During the month of May, Dickinson mourned the absence of her dear friend, Springfield Republican editor Samuel Bowles, who had embarked on a long European tour to improve his faltering health. This week, we explore Dickinson’s complex, intense relationship with Bowles, and the pressures placed on it, through the theme of foreign travel. Though Dickinson didn’t stray far from the Homestead, she eagerly consumed news from abroad in the Republican, in her readings, and in her correspondences. She looked forward to letters from Bowles, some of which she read in the Republican, where he offered rich and sharply observed descriptions of England, Ireland and the Continent.

Their relationship and correspondence underscore a fascination with travel, otherness, and foreign places that Dickinson exhibited in much of her writing, which is often expansive, reaching far beyond the narrow confines of Amherst life. Mary Kuhn points out that Dickinson frequently compresses vast distances into short lines or tight stanzas. For example, in 1860, Dickinson wrote:

If I could bribe them with a Rose

I’d bring them every flower that grows

From Amherst to Cashmere! (F176A)

We are swept from the Homestead to the Kashmir Valley near the Himalayas on the Indian subcontinent in one line. That flowers are the means of such compression points to Dickinson’s consciousness of the international mobility of plants, a theme we explored last week.

Cristanne Miller is particularly interested in Dickinson’s images of Asia and the East and finds that her “use of the idioms of Orientalism and foreign travel” in her poetry reaches a peak between 1860 and 1863. Miller explains:

Such images were not unusual at the time; Orientalism was in its heyday during the 1850’s in the United States. Dickinson both extended this discourse and critiqued it in her poems. She was part of a community that perceived its material pleasures, religious obligations, and republican principles, if not identity itself, in relation to global exchange, including commerce with … the “Orient” or “Asia.”

Dickinson read about the East, Asia, and the lands of the Bible in essays in the Atlantic and Harper’s, and her family library had copies of The Koran and several accounts of expeditions to places in the East. In her letters to her brother Austin, Dickinson teased him about his passionate reading of the Arabian Nights, which was immensely popular at the time and fostered a stereotypical and colonialist image of the East as a land of luxury and sensuality (see Letters 19, 22)

Dickinson’s fascination with places and her ability to “telescope” space, in the words of Christine Gerhardt, has opened a new direction in Dickinson scholarship that unfixes her from a narrow confinement to the small town of Amherst and her local surroundings, instead highlighting her global and even planetary dimensions.

“The Wounded Heart”

NATIONAL HISTORY

Springfield Republican, May 10, 1862, page 3

“Rev. Mr. Green, a colored local Methodist preacher, was five years ago sentenced to ten years’ imprisonment in Maryland, for having in his possession a copy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Numerous efforts have been made to secure his pardon, but without success until a few days since, when Gov. Bradford set him at liberty. He is required, however, to leave the state, and is already on his way to Canada.”

Springfield Republican, May 10, 1862, page 5

Williamsburg Evacuated. Details of Monday’s Operations. Advance Near Williamsburg, Monday evening, May 5th—To the Associated Press:—

When my dispatch was sent last evening that the indications were that our troops would occupy Williamsburg without much opposition.

Springfield Republican, May 10, 1862, page 5

Gen. McClellan Overtakes the Enemy.

The following was received at the war department Monday noon:—

Headquarters, Army of the Potomac, May 4th, 7 o’clock, p.m.—Our cavalry and horse artillery came up with the enemy’s rear guard in their entrenchments, about two miles this side of Williamsburg. A brisk fight ensued. … The enemy’s rear is strong, but I have force enough up there to answer all purposes. … The success is brilliant, and you may rest assured that its effects will be of the greatest importance. There shall be no delay in following up the enemy. The rebels have been guilty of the most murderous and barbarous conduct in placing torpedoes within the abandoned works, near wells and springs, near flag-staffs, magazines, telegraph offices … Fortunately, we have not lost many men in this manner—some four or five killed, and perhaps a dozen wounded. I shall make the prisoners remove them at their own peril. G.B. McClellan, Major General.

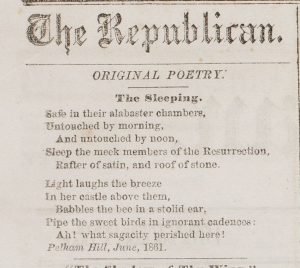

Springfield Republican, May 10, 1862, page 6 Poetry: “The Wounded Heart.”

Sweet, thou hast trod on a heart.

Pass! there’s a world full of men;

And women as fair as thou art

Must do such things now and then.Thou only hast stepped unaware,—

Malice, no one can impute;

And why should a heart have been there

In the way of a fair woman’s foot?It was not a stone that could trip,

Nor was it a thorn that could rend:

Put up thy proud underlip!

’Twas merely the heart of a friend.And yet peradventure one day

Then, sitting alone at the glass,

Remarking the bloom gone away,

Where the smile in its dimplement was,And seeking around thee in vain,

From hundreds who flattered before,

Such a word as, “Oh, not in the main

Do I hold thee less precious, but more!”Thou’lt sigh, very like, on thy part,

“Of all I have known or can know,

I wish I had only that heart

I trod upon ages ago!”

—Mrs. Browning

Springfield Republican, May 10, 1862, page 7: On A Rose.—Be An Epicure

I thank thee, fair maid, for this beautiful rose,

Fresh with dew from the favorite bowers;

In the bloom of the garden no rival it knows,

For the rose is the beef-steak of flowers.

“The Heart Wants What it Wants”

By April of 1862, Samuel Bowles had embarked on his trip to Europe, and on May 10th, Emily Dickinson—who was keenly affected by his absence—caught wind of his whereabouts in the Springfield Republican. His remarks, written from off the coast of Liverpool while en route to Paris, were printed alongside a set of letters from passengers aboard the Steamer China.

Bowles had entered Dickinson’s life four years earlier, in 1858, and became an important presence in Dickinson’s poems and correspondences. As biographer Richard Sewall notes, his place in her life is difficult to determine:

whether Bowles was at the exact center of it, or whether he was only a part of it, a catalyst in a mixing of many elements, cannot yet be said with certainty.

At any rate, Bowles was certainly someone to whom Dickinson addressed poems. Somewhere between 1861 and 1862—scholars disagree due to her shifting handwriting during this period—Dickinson wrote, “Dear Mr. Bowles,” accompanied by the following verse:

Victory comes late,

And is held low to freezing lips

Too rapt with frost

To mind it!

How sweet it would have tasted!

Just a drop!

Was God so economical?

His table’s spread too high

Except we dine on tiptoe!

Crumbs fit such little mouths –

Cherries – suit Robins –

The Eagle’s golden breakfast – dazzles them!

God keep his vow to “Sparrows,”

Who of little love – know how to starve! (F195A, J690)

The last line, Sewall points out, could indicate Dickinson’s willingness, even her desire to “exist on whatever bit (crumb) of love he chooses to bestow on her.” Hungry for such a crumb, Dickinson would have read the correspondences published in the Republican, pleased to hear the descriptions of Bowles’ journey:

We land at Liverpool this noon, and the end of our 18th day. The Irish and English shores in sight yesterday and today are a contrast in their rich green verdure and advanced cultivation to those we left behind us in America, dotted even in New Jersey and on Long Island with snow, or the barrenness and deadness of winter. The season here seems like the last of our May. We spend but a few days in England now, going over to Paris for May, and returning to Britain for the riper and richer June. We shall give you a gossiping personal letter occasionally, but a tour for health will not cheat its purpose with writing the oft repeated story of foreign travel. S. B.

Interestingly, the letter closes a temporal gap, as if to reduce the geographic distance between Bowles and his reader. “The season here seems like the last of our May,” he writes, likening England in late April to New England’s May. Thus, he and Dickinson occupy the same clime despite being separated by continents, and because the letter wouldn’t be published until May in the Springfield Republican, the “now” and the climate of the letter converge with the “now” and the climate of Amherst, upon Dickinson's reading.

Around the same time the Republican printed Bowles’ letter, Dickinson wrote to his wife, Mary Bowles, expressing sympathy for her husband’s absence.

When the best is gone I know that other things are not of consequence. The Heart wants what it wants – or else it does not care (L262).

Notably, the letter reads as if in two voices. Dickinson refers to “the heart” in general, as if to imply Mary’s, but also her own. The doubling continues and intensifies when she writes,

Not to see what we love, is very terrible – and talking – doesn’t ease it – and nothing does – but just itself.

The peculiar use of “we” in a letter ostensibly about another woman’s husband stands out, as Dickinson co-opts Mary’s longing for her husband as her own.

As we discuss in the poetry section for this week, one indication of Bowles’ influence is Dickinson’s fascination with “foreignness,” place names, and “exotic” references during this period. Cristanne Miller points out that Dickinson had some knowledge of Asia, and often criticized Western attitudes of racism and colonialist “Orientalism.” Miller observes that, as exemplified by Bowles’ letter from the steamer China,

news about foreign lands was delivered daily to the Dickinson household through the pages of the Springfield Republican.

Miller speculated that Dickinson’s isolation in Amherst, intensified by Bowles’ departure for Europe, was, perhaps, partly remedied by identifying “ontologically” with “epistemologies of foreignness” that brought her ever closer to him.

Reflection

Joe Waring

By the time Dickinson was writing in the year of the “white heat,” interest in “Orientalism” had reached its peak in the American cultural imagination (Miller 118). The “Orient,” as Edward Said notes in Orientalism, his groundbreaking work of postcolonial theory, is the

By the time Dickinson was writing in the year of the “white heat,” interest in “Orientalism” had reached its peak in the American cultural imagination (Miller 118). The “Orient,” as Edward Said notes in Orientalism, his groundbreaking work of postcolonial theory, is the

place of Europe’s greatest and richest and oldest colonies, the source of its civilizations and languages, its cultural contestant, and one of its deepest and most recurring image of the Other

—and an interest in identity-formation in opposition to those images played out throughout the West (Said 1). Moreover, Said considers “Orientialism” to be not only a set of oppositions and ideas, but a

mode of discourse with supporting institutions, vocabulary, scholarship, imagery, doctrines, even colonial bureaucracies and colonial styles,

all of which would become fodder for Dickinson’s poetic lexicon (Said 2). In fact, Miller locates about seventy different references to the “Orient” in Dickinson’s poetry, as she played her role in a long-established tradition of evoking “Oriental” tropes in writing—a discourse she ultimately perpetuated as well as criticized (Miller 118-119). Understanding “Orientalism” in this way—as a discourse, Said contends, allows us to trace the

enormously systematic discipline by which European culture was able to manage—and even produce—the Orient politically, sociologically, militarily, ideologically, scientifically, and imaginatively during the post-Enlightenment period.

Dickinson’s poetry—in its frequent references and deep interest in the “Orient”—urgently calls to be understood as part of this process (Said 3).

Why was Dickinson so interested in the “Orient” in the first place? To start, she voraciously consumed the literature, news, and culture that she came into contact with. As Miller points out, “news about foreign lands was delivered daily to the Dickinson household through the pages of the Springfield Republican,” and she would have developed a deep interest in “foreignness” as her close friend, Samuel Bowles, set out for Europe in 1862, leaving her behind in Amherst. She also occupied a social milieu in which everyone else was fascinated by the “Orient” too. New Englanders were constantly filling their homes with “knickknacks, the fine china dogs and cats, the pieces of oriental jade, the chips off the leaning tower of Pisa” (Tate 155). What’s more, Dickinson visited Peter’s Chinese Museum in 1846, which documented the Anglo-Sino Opium War, spurring great interest in the use of narcotics (Li-hsin 9).

Among American writers, Dickinson was not alone in her invocation of “Orientalism.” Miller notes that “Emerson, Whittier, Bayard Taylor, Lydia Maria Child, and Whitman” were all deeply interested in “Asian scripture and literature” in a way that surpassed Dickinson (Miller 129). The transcendentalists in particular looked to “Asian philosophy and religion as a source of spiritual inspiration or knowledge” (129). Whitman, even more problematically, viewed “Asia as a natural partner to or goal of American westward expansion”—a form of U.S. imperialism that Dickinson largely avoided (130). Where the transcendentalists sought to incorporate the “Orient” both into their spirituality, philosophy, and—imperialistically—their geography, Dickinson saw Asia as an “unknown” that could inspire insight into her understanding of her own context.

While Dickinson’s use of “Orientalist” references was in line with historical trends and interests, what she read and learned about the “Orient” may have expanded her ability to think about contemporary issues at home, thus participating in what Said sees as a trend of oppositional identity formation. Dickinson’s 1864 poem, “Color – Caste – Denomination” (F836), which in its title alone addresses three pressing issues of American society, makes use of “Oriental” imagery to comment on contemporary social and political issues:

Color – Caste – Denomination -

These – are Time's Affair -

Death's diviner Classifying

Does not know they are -

As in sleep – all Hue

forgotten -

Tenets – put behind -

Death's large – Democratic

fingers

Rub away the Brand -

If Circassian – He is careless -

If He put away

Chrysalis of Blonde – or Umber -

Equal Butterfly -

They emerge from His Obscuring -

What Death – knows so well -

Our minuter intuitions -

Deem unplausible

Race, socioeconomic status, and religion—topics that are well-documented in Dickinson’s poetry, as well as in the blog posts for several of the weeks in 1862—were important to Dickinson’s understanding of the “Orient,” just as they were in the United States; they are, universally speaking, “Time’s Affair,” unified across continents insofar as “Death’s diviner Classifying / Does not know they are.” Death’s “large – Democratic / fingers” are democratic precisely because they touch everyone, everywhere. “If Circassian,” she seems to ask, the effect is the same as if the question were, “If from Amherst?” The poem makes frequent reference to skin tone and race: “color,” “Hue,” “Blonde,” “Umber”—a lexicon that maintains its urgency whether in reference to American abolition or the Circassians.

What, then, do we make of these references? As Said points out, the academic and literary traditions of “Orientalism” are not innocuous; “European culture,” he points out, “gained in strength and identity by setting itself off against the Orient as a sort of surrogate and even underground self” (Said 3). The natural consequence of identity formation that opposes itself to an “other,” Said continues, is a “flexible positional superiority, which puts the Westerner in a whole series of possible relationships with the Orient without ever losing him the relative upper hand” (7). As such, there is much to be criticized, examined, and understood about conceptions of “otherness” and “foreignness” in Dickinson’s frequent evocation of the “Orient.” Miller offers some consolation in that, though Dickinson certainly participated in a troubling and long history of “Orientalism,” she did so with her characteristic empathy:

Instead, Dickinson’s Orientalism borrows from and rewrites the symbolic geographies of her era. While popular geographies portrayed people in relation to stereotyped coordinates of the South, North, East, and West, her representations of Asians were without exception sympathetic, even if romantically or ambivalently so (Miller 130).

Sources

Hsu, Li-hsin. “Emily Dickinson's Asian Consumption.” The Emily Dickinson Journal, vol. 22, no. 2, 2013, pp. 1-25,135.

Miller, Cristanne. Reading in Time: Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012, 118-146.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books, 1994.

Tate, Allen. "New England Culture and Emily Dickinson." The Recognition of Emily Dickinson: Selected Criticism Since 1890. Ed. Caesar R. Blake and Carlton F. Wells. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1965.

bio: Joe Waring is a Dartmouth ’18, who studied English, Italian, and Linguistics. He came by Dickinson like most, in his high school classroom, where he memorized “It Feels A Shame To Be Alive,” and was happy to revisit Dickinson in Professor Schweitzer’s class, “The New Emily Dickinson: After The Digital Turn.” His favorite Dickinson poem is, unquestionably, “The Mushroom is the Elf of Plants” (J1298, F1350).

Sources

Overview

Gerhardt, Christine. “Often seen–but seldom felt”: Emily Dickinson’s Reluctant Ecology of Place.” The Emily Dickinson Journal 15.1 (2006): 73.

Kuhn, Mary. “Dickinson and the Politics of Plant Sensibility.” ELH, 85:1 (Spring 2018), 143-44.

Miller, Cristanne. Reading in Time: Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012, 118-20.

This week in History:

Springfield Republican, Sat May 310 1862.

This week in Biography:

Miller, Cristanne. Reading in Time: Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012, 119.

Sewall, Richard. The Life of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980, 492-93.

Still, Cristanne Miller argues that the “being edited” argument—though clearly a concern for Dickinson—is insufficient to explain why so much of her poetry went unpublished. Miller points to two compelling reasons that go beyond Dickinson’s preoccupation with editorial interference. First, her most profound poems deal with matters of life, death, and loss in

Still, Cristanne Miller argues that the “being edited” argument—though clearly a concern for Dickinson—is insufficient to explain why so much of her poetry went unpublished. Miller points to two compelling reasons that go beyond Dickinson’s preoccupation with editorial interference. First, her most profound poems deal with matters of life, death, and loss in