Dickinson Day

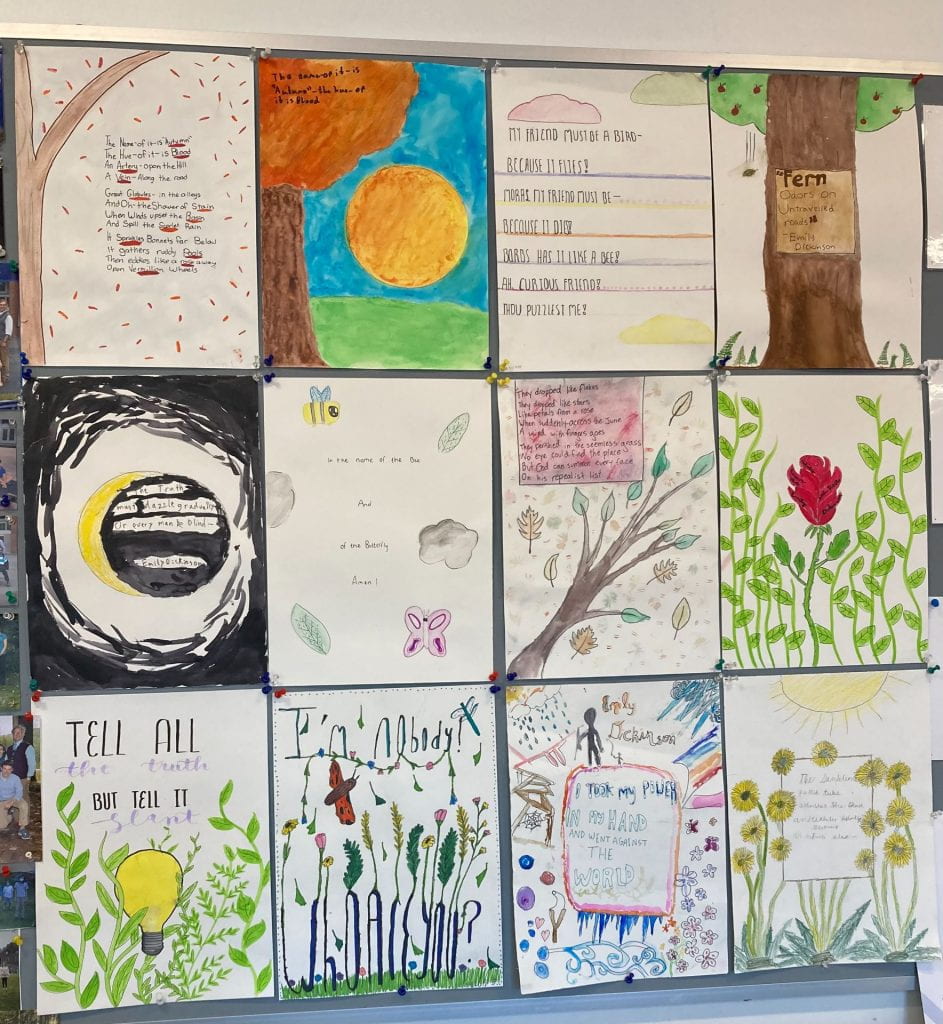

On December 10th, 2018, we journeyed down the Connecticut River Valley in a large yellow school bus to Amherst, Massachusetts, to celebrate Dickinson’s birthday in her home town. It was a bright, cold day and, as we like to say in the “Upper Valley,” “at least it wasn’t snowing!”

The students in Steve Glazer’s 7th grade class from Crossroads Academy in Lyme, New Hampshire, were restless with anticipation. As the Pioneer Valley opened up and flattened out, dotted with farms and old tobacco drying sheds, Steve tried to focus the students’ attention with his characteristic call and response: “Where was Emily Dickinson born?” he called through cupped hands to be heard over the rattling bus. “In Amherst, Massachusetts,” the children called back. “What year?” – “In 1830” and so on.

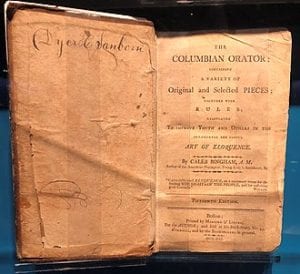

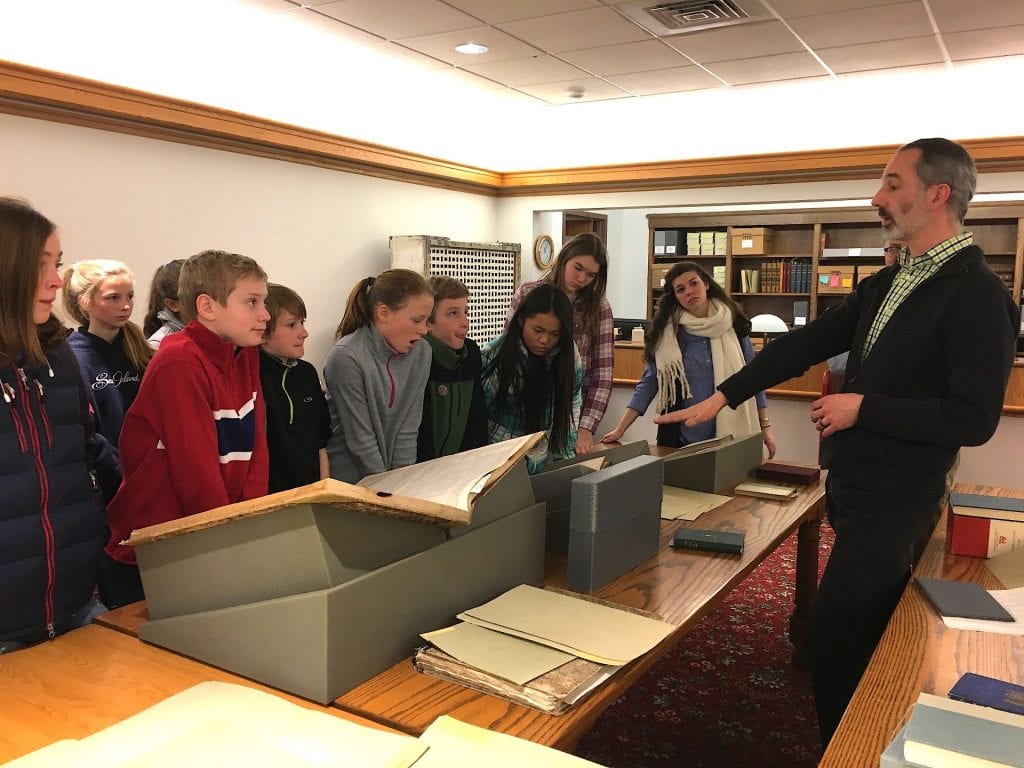

We stopped first at Special Collections in the basement of the Frost Library at Amherst College. Archivist Michael Kelly had a stunning display of objects and manuscripts laid out for us, including a lock of Dickinson’s hair, which is surprisingly ruddy. He showed us manuscripts of poems from early, middle and late in Dickinson’s writing career to illustrate the palpable changes in her handwriting. He was surprised and impressed when he held up the manuscript of a poem, announced its first line and, as if on cue, the entire class recited the poem with one voice. “I see I can up my game with this group,” he responded.

We stopped first at Special Collections in the basement of the Frost Library at Amherst College. Archivist Michael Kelly had a stunning display of objects and manuscripts laid out for us, including a lock of Dickinson’s hair, which is surprisingly ruddy. He showed us manuscripts of poems from early, middle and late in Dickinson’s writing career to illustrate the palpable changes in her handwriting. He was surprised and impressed when he held up the manuscript of a poem, announced its first line and, as if on cue, the entire class recited the poem with one voice. “I see I can up my game with this group,” he responded.

We then walked over to the Homestead for tours of the house and Dickinson’s bedroom. Perhaps the highlight of the day occurred next door at the Evergreens, where one of the students played her original piano composition inspired by the poem, “ ‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers.” The Emily Dickinson Museum graciously allowed her to use the Evergreen’s Steinway and we all crowded into Sue and Austin’s parlor to hear it. You can see a video of this performance and others that occurred in the Evergreens as well as more of the students’ projects in the Poems section of this week’s post.

Then, back to the Homestead where students recited the poems they had memorized in the double parlor with the doors thrown open, under the watchful eyes of the Dickinson children’s group portrait. And, finally, a quiet walk through West Cemetery, flooded with winter afternoon light, to the Dickinson family plot, where we surrounded Dickinson’s gravestone and sang, “This is my letter to the World.” I think, I hope, Emily was listening.

Updates: We did a similar trip on December 10, 2019. In 2020, Steve's class did a virtual tour of the Dickinson museum and pre-recorded their birthday rendition of "My letter to the world," which the museum used to close out their Dickinson birthday party Zoom. In 2021, class took a virtual field trip to the Dickinson Archive at Amherst College, where archivist Mike Kelly showed the students a handful of treasures from the archive: Charles Temple's cut paper silhouette, 1845; Dickinson's daguerreotype, ca. 1847; a lock of Dickinson's hair sent to Emily Fowler Ford, ca. 1853; the second possible daguerreotype (Dickinson with Kate Scott Turner); manuscripts of "In this short life," "The way hope builds his house," "I suppose the time will come," and Fascicle 1. The tour concluded with students reciting poems from memory. Every student recited at least one poem; several students presented two, three, four, or even five poems. The students celebrated with song ("This is my letter to the world"), cake, and cupcakes.

In 2022, Steve's class travelled to Amherst again for a tour in person, but Ivy had Covid, and could not join them. They are scheduled for an in-person Dickinson Day in Amherst this year on Monday December 11, 2023.

“The Reverent Faith of Childhood”

Springfield Republican, December 20, 1862

Review of the Week, page 1

“Disappointment and disaster cover the week’s history. The march to Richmond by way of Fredericksburg has begun and ended. Our army is in camp again on the north side of the Rappahannock, but weaker by the loss of fifteen thousand men and by the consciousness that it has failed in one of its greatest efforts.”

The National Currency System—Its Advantages to New England, page 2

“[A currency] is designed as a medium of exchange to facilitate the business intercourse [of the people], enabling them to buy and sell, and to receive and make payments. The most indispensable qualities for this medium are, that it should be simple, uniform, and of undoubted value. The local paper currencies of the United States have not these qualities.”

The Reconstruction Puzzle, page 4

“The true way to settle the question as to how the South shall be got back into the Union is to destroy the rebel armies. When the rebellion is ‘crushed out,’ the theoretical difficulties of the problem will disappear. But the theoretical difficulties have very little reality to them. They are chiefly got up by those ingenious amateurs in state craft who think in some way to circumvent the stubborn facts of the situation and get rid of the hard necessity of fighting down the rebellion. The territorial lines, the constitutions and laws of the states in rebellion still exist. South Carolina is still a state, and her state officers elected legally are her rightful state authorities. The act of secession is null and void, and all the acts connected with it—if we can make it so by success in the war.”

Books, Authors, and Arts, page 6

“This is a literal age. While seeking to master material forces, they have well-nigh mastered us, leading us to rest content with physical facts, instead of regarding them as the lowest and coarsest forms of subtle spiritual truth. We have lost the reverent faith of childhood; we are like raw schoolboys, who, knowing a little, fancy they know all. Our juvenile libraries contain no fabulous legends or fairy tales; they seem to have been selected by clerical Gradgrinds and offer only ligneous lessons and ferruginous facts.”

Hampshire Gazette, December 23, 1862

Poetry, page 1 [Bayard Taylor (1825-1878) an American poet, literary critic, translator, travel author and diplomat.]

A New Cabinet, page 2

“The entire cabinet of President Lincoln, with the exception of Secretary Stanton, is said to have resigned. It seems well established that Secretary Seward has resigned the position of Secretary of State, and his son that of assistant secretary. These statements will take the country by surprise, as there had been no previously well-founded rumors of any proposed changes in the cabinet.”

Atlantic Monthly, December 1862

from Lyrics of the Street (Part III) by Julia Ward Howe [see earlier parts of the series]

III.

She carries no flag of fashion, her clothes are but passing plain,

The Charitable Visitor.

Though she comes from a city palace all jubilant with her reign.

She threads a bewildering alley, with ashes and dust thrown out,

And fighting and cursing children, who mock as she moves about.

Why walk you this way, my lady, in the snow and slippery ice?

These are not the shrines of virtue, — here misery lives, and vice:

Rum helps the heart of starvation to a courage bold and bad;

And women are loud and brawling, while men sit maudlin and mad.

I see in the corner yonder the boy with the broken arm,

And the mother whose blind wrath did it, strange guardian from childish harm.

That face will grow bright at your coming, but your steward might come as well,

Or better the Sunday teacher that helped him to read and spell. …

Harper’s Monthly, December 1862

Love by Mishap, page 47 [by Edward Howard House]

“There is nothing in the world like the beautiful devotion of a woman to the sick. She feels no toil, nor pain, nor timid terrors. If she has grief, she hides it, lest it add one feather’s weight to the afflictions of her charge. Her courage rises as her hopes recede. The grim spectre that hovers and threatens may appall her, but she gives no sign. Her eye is clear and gentle; her voice soft and sweet as the breath of summer; her touch so tender that the simplest kindly office soothes like a caress. The dawn of her smile chases away suffering as light dispels the mists of the universe. In her weakness she is stronger than the strong.”

“This Slew all but Him”

Besides the neighborhood urchins, with whom (as we learned in the earlier post on Children) Emily Dickinson was reputedly a popular figure, she had a few young people in her daily world. Notably, the three children of Sue and Austin, who proved to be crucial to her life, writing, and reputation.

The eldest of these was Edward, called “Ned.” He was a difficult child who was plagued with illness and eventually became a librarian at Amherst College, but died at age 37 of heart problems. Shortly after he was born, Dickinson sent this arch poem to Susan:

Is it true, dear Sue?

Are there two?

I should'nt like to come

For fear of joggling Him!

If you could shut him up

In a Coffee Cup,

Or tie him to a pin

Till I got in –

Or make him fast

To "Toby's" fist –

Hist! Whist! I'd come! (F189, J218)

EDA comments: “The bottom of the manuscript, containing the last line of the poem and the signature "Emily," is now missing. It also carried a family note identifying the occasion and explaining that Toby was the cat.”

But by early March 1866, Dickinson wrote to her friend Elizabeth Holland:

We do not always know the source of the smile that flows to us. Ned tells that the Clock purrs and the Kitten ticks. He inherits his Uncle Emily’s ardor for the lie (L315).

Note the gender crossing in Dickinson’s self-description. Despite her early fears of being displaced in Susan’s affections by her nephew Ned, they became cheerful companions, sharing a love of words. Ned’s sister Martha recalled their relationship, in her soft-focus memoir:

His love of books kept him near her, and his sense of humor delighted her. He saved all his funniest stories, his gift of mimicry, his power of offhand description for her; and if his Aunt Lavinia went to a neighbor’s for an evening chat, Ned was usually to be found in front of the fire with his Aunt Emily, perched on the edge of a stiff-backed chair, the light of the flames flickering over her white dress, her hands crossed for permanence, but in easy position for flight should their talk be broken by an unwelcome knock.

Martha, called “Mattie” by her intimates, was the family memoirist, a poet and an early editor of Dickinson’s works. She was the middle child of Susan and Austin. In a letter to Susan away on holiday in Europe, Aunt Emily described her as “stern and lovely–literary they tell me–a graduate of Mother Goose and otherwise ambitious” (L333, autumn 1869). Caught in the middle of her parents’ tumultuous relationship, Mattie was a staunch supporter of her mother. After her own failed marriage to an erstwhile “count” Bianchi and her mother’s death, Martha resided at the Evergreens and in 1913 began publishing Dickinson’s poetry and her reminiscences of Dickinson and the family. She eventually published eight volumes of Dickinson’s writings.

Although scholars have sharply criticized her editing of the poems and her sentimentalized recollections, which contributed to the myth of Dickinson as a woman in white who renounced the world because of frustrated love, Bianchi was the first editor to try to faithfully reproduce Dickinson’s original lineation as it appeared in the poem manuscripts. As Jonathan Morse notes in his helpful essay on the complicated publication history of Dickinson’s work, Bianchi was “ahead of her time” in this regard. The 1924 Complete Poems, which she edited, though in no way “complete,” brought more of Dickinson’s poetry into the world than ever before.

Last but not least is the third child of Susan and Austin, Thomas Gilbert, called “Gib” by the family. Born to his parents in their middle years and much younger than his siblings, Gib was adored by all, especially his aunt Emily. Biographer Alfred Habegger recounts this story about them:

Once, when little Gilbert was in kindergarten and boasted about a beautiful white calf that proved to be imaginary, his teacher reprimanded him for the sin of lying and made him cry. Sue tried to convince the benighted woman of the validity of the imagination, but Aunt Emily, as her niece [Martha Bianchi] recalled, was too indignant for reasoning and “besought them one and all to come to her, she would show them! The white calf was grazing up in her attic at that very moment!” A note she drafted for the wounded boy to take to his teacher had a poem on “The vanity . . . / Of Industry and Morals” (F 1547B) and pointedly contrasted the punitive Jonathan Edwards with Jesus.

When Gib, barely 8 years old, died suddenly from typhoid fever, Dickinson reportedly rushed over to the Evergreens to be with the family, the first time she had visited there in fifteen years. She wrote to Elizabeth Holland about this death (L873, late 1883) and wrote several poems and letters of condolence to Susan about Gib (see L886, F1624, F1666), one of which asserted:

Some Arrows slay but whom they strike –

But this slew all but him … (F1666)

Gib’s death deeply affected the family and apparently precipitated Austin’s affair with the young and alluring Mable Loomis Todd, who, with Thomas Higginson, was the first editor of Dickinson’s poetry after her death. Their affair caused further divisions and enmity “between the houses.”

Although Dickinson would suffer other losses around this time—the death of her mother and Judge Otis Lord, a man whom she loved (but whose offer of marriage she refused)—it was Gib’s death that, some say, contributed to her final illness. There is nothing like the death of a child to reinforce the blighting existence of frost as perennial threat to the youth and innocence of the earthly garden.

Reflection

Eliot Cardinaux

Have you ever come across an ED poem about Disillusionment? Anxiety? Reality? About how words themselves can be affected by life’s challenges, at least within us, as we grow into and out of and recede from them?

Have you ever come across an ED poem about Disillusionment? Anxiety? Reality? About how words themselves can be affected by life’s challenges, at least within us, as we grow into and out of and recede from them?

I wonder because her ideals were so wrapped up in her status as a woman at that time, there’s often a bite to what she says.

I was thinking of the way in which words can be struggled with, the way meanings wrap around their things, in language and without, how certain words can produce in us, personally, the need to grapple with how we live, the questions they provoke in us.

While their letters remain the same, each of these words, like tattoos, reel in the years or cause us to, in both senses of the word. A tattoo can change its meanings over time, acquire new ones, and shed those that life has caused us to question, their validity.

A tattoo of a gull caught by a fishing hook might be a good analogy, because to reel, to be struck, for example, like an eagle in flight by a crow, is to lose all sense of balance, and yet fishing for something down below the surface, we can never possess it — whatever mystery that fish holds, the weight of its bite, the force of its pull — without reeling it in. Some violence there, perhaps, in pursuit of the unknown.

Some thoughts on a cold, wet Monday as the snow thaws.

This ― Illusion― Meant

in the loop ― and out

it’s nothing ― personal if

you stay ― calm ― you

stay ― an anxious ― wreckdid you want me ― to scorn

the ear ― did you need

my throat ― to sing

did you want me ― hereto live ― in an unknown

word ― meanings coil ― around

their things ― havoc rings ― my head

a hydra’s ― lizard’s tail ― expendablewrap ― your tongue ― around

a dash ― in the way ― I need you

there ― this way ― to go

did you want me ― deadadapting ― hand in

hand ― with blindness

to the drug ― is the score

the truth ― that ― malleableout the loop ― and in

it’s nothing ― special

you stay ― calm ― to

stay ― an anxious ― wreck

bio: Eliot Cardinaux

Poet, Pianist, Multimedia Artist

Sources

History

Atlantic Monthly, December 1862

Harper's Monthly, December 1862

Hampshire Gazette, December 23, 1862

Springfield Republican, December 20, 1862

Biography

Bianchi, Martha Dickinson. Emily Dickinson Face to Face: Unpublished Letters with Notes and Reminiscences by Her Niece, Martha Dickinson Bianchi. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1932, 169.

Habegger, Alfred. My Wars Are Laid Away in Books: The Life of Emily Dickinson New York: Random House, 2001, 548.

Morse, Jonathan. “Bibliographical Essay.” A Historical Guide to Emily Dickinson. Ed. Vivian Pollak. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004, 255-83, 258-60.