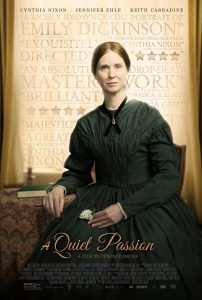

Sometime in early August of 1862, Dickinson wrote her fifth letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson and enclosed two poems, “I cannot dance upon my toes” (F381A, J326) and “Before I got my Eye put out” (F336A, J327). It is a long letter covering themes such as self-governance, waywardness, “Orthography,” seclusion, her dog Carlo, fraud and literary imitation, and ends with an offer to share with Higginson one of the three portraits of Elizabeth Barrett Browning sent to Dickinson by friends. Apparently, every self-respecting friend of Emily must have a portrait of this extraordinary writer, who died in June 1861 — or is this offer meant as a substitute for the portrait of Dickinson that Higginson requested in his last letter, which she said she did not have?

Sometime in early August of 1862, Dickinson wrote her fifth letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson and enclosed two poems, “I cannot dance upon my toes” (F381A, J326) and “Before I got my Eye put out” (F336A, J327). It is a long letter covering themes such as self-governance, waywardness, “Orthography,” seclusion, her dog Carlo, fraud and literary imitation, and ends with an offer to share with Higginson one of the three portraits of Elizabeth Barrett Browning sent to Dickinson by friends. Apparently, every self-respecting friend of Emily must have a portrait of this extraordinary writer, who died in June 1861 — or is this offer meant as a substitute for the portrait of Dickinson that Higginson requested in his last letter, which she said she did not have?

In her letter, Dickinson repeats many of Higginson’s questions and comments, giving us a fuller sense of his interests in her and their correspondence. She replies with alluring but enigmatic answers. This week, we will examine this letter, the two poems included in it, and other poems that speak to the themes both letter and poems suggest as pertinent to this crucial, developing friendship.

“Pure Christianity Never Was, and Never Can Be, the National Religion of Any Country upon Earth”

Springfield Republican, August 9, 1862

Progress of the War, page 1

“The great event of the week is the call by the president for 300,000 militia from the states for nine months’ service. We have recovered from the failure of the second ‘forward-to-Richmond’ movement much quicker than the first, and the third movement is now in progress. The president has announced that Gen. Hallock has undivided control of the operations of the war.”

Do We Want Canada? page 4

“Our British cousins evidently think we do. The revelations made in the latest debates in the British parliament as to the defense of Canada are curious and instructive. The idea that the United States’ desire to absorb the Canadas and other British American provinces, and will ultimately do so, manifestly accounts for much of the hostile feeling towards this country, and especially for the strong wish to see the Union broken under and our power thus crippled for generations to come.”

Stand by the Cause, page 4

“The day for petulant complainings and critical doubts is long gone by, and the hour come when every man should throw himself with complete sympathy and new enthusiasm into the spirit of every onward movement. Let us talk victory—think victory—dream victory—and it shall come.”

Poetry, page 6 [by Horatius Bonar]

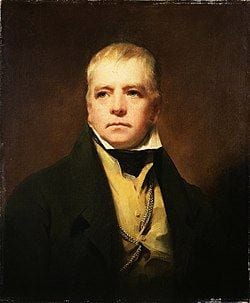

Books, Authors and Art, page 7

“The seventh and eighth volumes of Lockhart’s Life of Walter Scott are books of personal history and charming literary gossip, being largely composed of extracts from the novelist’s diary and letters to eminent friends. Persons who have long had a satisfactory edition of the novels would find their value much enhanced by the comments furnished in these inviting volumes of the author’s life.”

Hampshire Gazette, August 12, 1862

Christianity, page 1

“Pure Christianity never was, and never can be, the national religion of any country upon earth. It is a gold too refined to be worked up with any human institution, without a large portion of alloy; for no sooner is this small grain of mustard seed watered with the fertile showers of civil emoluments, then it grows up a large spreading tree, under the shelter of whose branches and leaves the birds of prey and plunder will not fail to make themselves comfortable habitations, and thereby deface its beauty and spoil its fruits.”

page 2

“The New York Times has got to be the sensation paper of the day.”

Amherst, page 3

“The Amherst recruits, with others from neighboring towns, left for camp at Pittsfield on Monday, in charge of Lieut. M. W. Tyler of Amherst.”

“Syllables of Velvet / Sentences of Plush”

August 1862 was a time of waiting for Dickinson. The excitement of the Amherst Commencement on July 10, and all the events, visitors and entertaining that entailed for the Dickinsons, was over. Dickinson gives evidence of enjoying the hoopla, writing to her cousin Eudocia Flynt from Monson sometime before July 21,

Dear Mrs Flint

You and I, did’nt finish talking. Have you room for the sequel, in your Vase?

All the letters I could

write,

Were not fair as this –

Syllables of Velvet –

Sentences of Plush –

Depths of Ruby, undrained –

Hid, Lip, for Thee,

Play it were a

Humming Bird

And sipped just

Me –

Emily. (L270)

She enclosed a flower with this lush letter-poem about her preference for talking face to face, which emerges as a theme in this week’s selections.

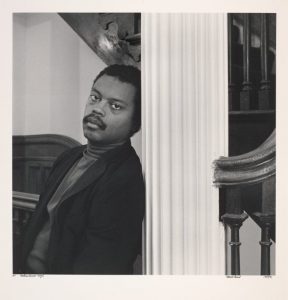

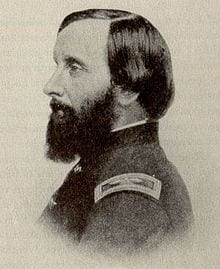

Then, in August, Dickinson wrote her long fifth letter to Higginson, who was busy at the time training raw recruits from his adopted hometown of Worcester, Massachusetts to serve in the 51st regiment. “My company is admitted to be the best drilled & disciplined in the regiment,” he announced with pride in a letter of November 9 from a camp outside the town, as he waited for instructions about the regiment’s deployment. Five days later, he received a letter from Brig. General Rufus Saxton, another Massachusetts man with ties to the Transcendentalist circles of which Higginson was a member, who was enlisting formerly enslaved people as troops for the Union army and offered Higginson command of this new regiment. Higginson left for South Carolina within days to take up this mission.

Another letter Dickinson wrote at about the same time to Samuel Bowles, still traveling in Europe, expresses her longing to have her friend back:

Summer a’nt so long as it was, when we stood looking at it, before you went away, and when I finish August, we’ll hop the Autumn, very soon – and ’twill be Yourself. … I tell you, Mr Bowles, it is a Suffering, to have a sea – no care how Blue – between your Soul, and you. … It is easier to look behind at a pain, than to see it coming. A Soldier called – a Morning ago, and asked for a Nosegay, to take to Battle. I suppose he thought we kept an Aquarium. (L272)

The last remark about the soldier has been cited as evidence of Dickinson’s aloofness, elitism, and distance from the Civil War and its ongoing death toll, and her remark about the aquarium, though opaque, does seem snarky. But in the context of a comment about the pain of separation, this comment can be read as a recognition of and sympathy with the Soldier’s approaching rupture from family and friends. Dickinson offers the Soldier as an example of someone who “see[s] the pain coming” by contrast with herself, who has already faced the pain of separation from Bowles, which is almost over, and is looking back at it as aftermath with some relief.

Reflection

Jason Hoppe

Several observations and themes in this post resonate with me, though I’m not yet sure how or whether to connect them. The post puts together such a provocative tapestry, for instance, of Dickinson’s varied interests in “faces”—in her preference for face-to-face meetings over correspondence, in the faces she makes of mountains in the poem about waywardness mentioned (F745), and even in how she insists in her fifth letter to Higginson on taking him at the very “face value,” as the post puts it, that she makes it quite difficult for him to reciprocate (in part by declining to send him any self-portrait other than a metaphorical one, or one of Elizabeth Barrett Browning).

Several observations and themes in this post resonate with me, though I’m not yet sure how or whether to connect them. The post puts together such a provocative tapestry, for instance, of Dickinson’s varied interests in “faces”—in her preference for face-to-face meetings over correspondence, in the faces she makes of mountains in the poem about waywardness mentioned (F745), and even in how she insists in her fifth letter to Higginson on taking him at the very “face value,” as the post puts it, that she makes it quite difficult for him to reciprocate (in part by declining to send him any self-portrait other than a metaphorical one, or one of Elizabeth Barrett Browning).

Maybe the first item that stood out to me in the post, though, has something to do with this too, albeit in a roundabout way: it was the brief newspaper poem, “Be True,” by Horatius Bonar.

I read it a couple times, increasingly bemused. Of course Bonar is writing in the same hymn meter that Dickinson drew from—and actually innovated. But how sententious and banal do Bonar’s lines read next to hers! I couldn’t help but wonder over how differently, how much more complexly, being “true” plays out in her early correspondence to Higginson. Bonar seems to take being “true” to be readily self-evident; thinking and living “truly” is rather a simple affair and, ultimately, the solution to global hunger. It’s a sentimental vision for which I think Dickinson would have little regard, though she might have delighted in parodying it.

I read it a couple times, increasingly bemused. Of course Bonar is writing in the same hymn meter that Dickinson drew from—and actually innovated. But how sententious and banal do Bonar’s lines read next to hers! I couldn’t help but wonder over how differently, how much more complexly, being “true” plays out in her early correspondence to Higginson. Bonar seems to take being “true” to be readily self-evident; thinking and living “truly” is rather a simple affair and, ultimately, the solution to global hunger. It’s a sentimental vision for which I think Dickinson would have little regard, though she might have delighted in parodying it.

When she first writes to Higginson, of course, Dickinson asks him to “tell me what is true” (L260). She counts herself among the “True” in her third letter to him (L265), and in her fourth verifies that he does “truly consent” to the relationship she establishes between them while also congratulating him for being “true” about an earlier judgment (L268). And she opens the fifth letter by thanking him, in advance, for the “Truth” of his judgment about her poems (L271). However, given their context, nothing about these moments of indexing what is “true” and “truthful”—which, for Dickinson, raise hard, intersecting questions about loyalty, accuracy, insight, and honesty—is simple or straightforward. But while there is coyness and uncertainty in these letters to Higginson, they also do not lack for sincerity. Dickinson is nothing if not ingenuous when playing with the truth. But she also evinces a more realistic understanding of the difficulty of getting at what is true, performing the same, and the consequences of such performances.

Take “I cannot dance upon my toes”(F381A). As the post notes, the deeply performative nature of this poem only further complicates the ostensibly tutorial relationship that Dickinson establishes with Higginson. How is he to “tell [her] what is true,” when she (or her surrogate speaker) needs no man’s instruction to access the “Ballet Knowledge” within the mind? In this poem, though, Dickinson also relentlessly distinguishes what is true, and “full as Opera,” in the self and what is outside of it, at least so far as the “placards” of publics go. The majority of the poem renounces the latter—that’s quite different than the lockstep relationship of true self and world imagined, say, in Bonar’s hymn. This is not to declare, as critics of old, that Dickinson abandons the world, but it is to make clear that, following fascinating interpretations like Runzo’s, she realizes that facing it requires more deftness and nuance for some than others.

bio: Jason Hoppe is an Associate Dean and Associate Professor at the United States Military Academy (West Point). He is working to complete a book on how a number of major nineteenth-century New England authors brought together their lives and literary achievements. Articles from the project on Emily Dickinson and Margaret Fuller have been published in Texas Studies in Literature and Language and ESQ: A Journal of the American Renaissance, respectively.

Sources:

History

Hampshire Gazette, August 12, 1862

Springfield Republican, August 9, 1862

Biography

Dickinson, Emily. The Letters of Emily Dickinson. Eds. Thomas Johnson and Theodora Ward. 3 vols. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958, 414.

Kytle, Ethan J. “Captain Higginson Takes Command.” The Opinion Pages, November 16, 2012.