First Week of the Crossroads Academy Collaboration

For the last few years, we have been collaborating with the 7th grade class at the Crossroads Academy in Lyme, NH, a few miles down the road from Dartmouth College. Our friend, Steven Glazer, has developed an amazing month-long unit on Emily Dickinson that culminates with a trip to Amherst, MA, on December 10th, Dickinson’s birthday! The class visits the archives at Amherst College to view Dickinson’s manuscripts and takes a tour of the Homestead at the Emily Dickinson Museum, where students recite poems by Dickinson they have memorized—in the parlor! It concludes with a requisite visit to Dickinson’s grave in West Cemetery down the street from her house.

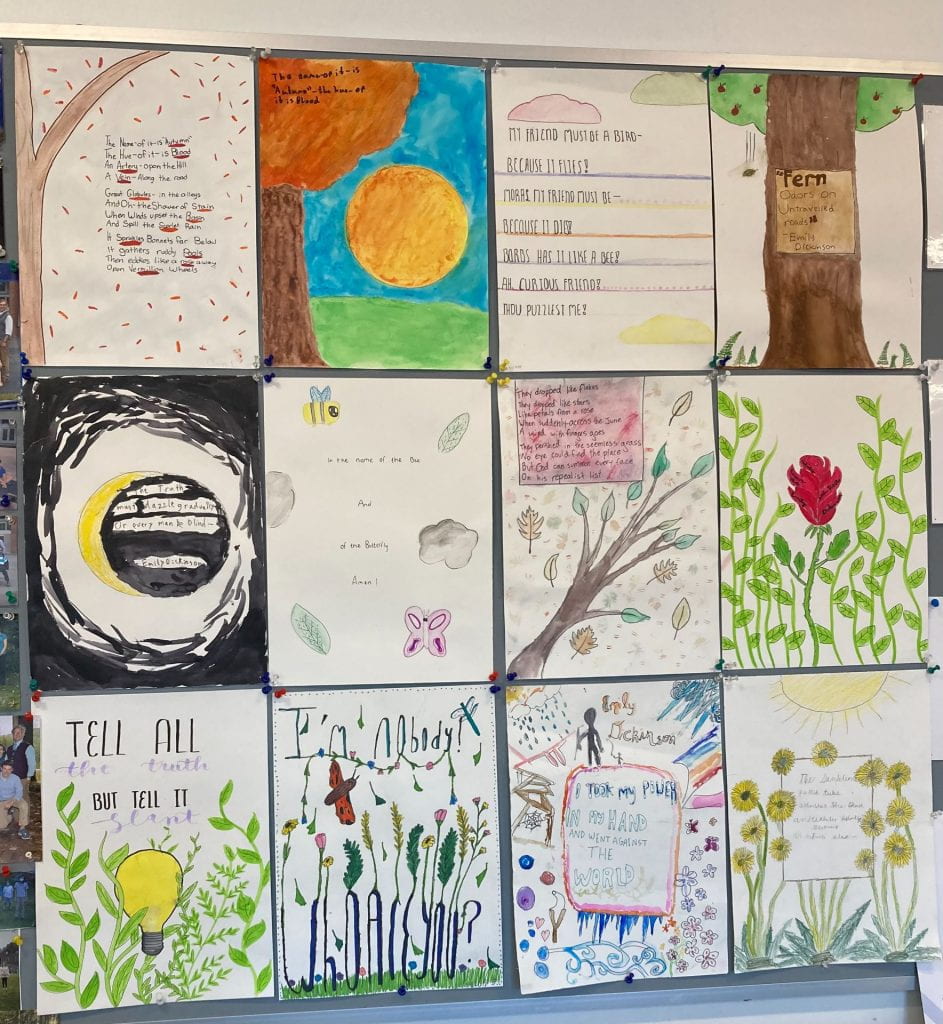

At the beginning of the unit, I journey (in 2020 and 2021: remotely) to Steve’s class to introduce the many digital tools and websites on Dickinson, including White Heat, and especially the Emily Dickinson Archive that makes the manuscripts of Dickinson’s poems accessible to everyone. Steve’s challenging unit on Dickinson has several related themes: the power of language, the power of wonder, and the question, what is freedom? Steve will explain his project-based approach to Dickinson in more detail in this post, and for this week and the week of December 17th we will showcase the marvelous and varied projects by his students in the Poems section, so you can see what they achieved and what about Dickinson captivated and absorbed them.

This week, we will also use the occasion of this collaboration to explore Dickinson’s relation to children and how her poetry was originally marketed to a young audience in a watered-down form. The Crossroads 7th graders are reading an undiluted Dickinson. It is thrilling to watch them rise to this challenge and share their unabashed enthusiasm for Dickinson and poetry.

“Rise in your Might then, Women of the North!”

Springfield Republican, December 6, 1862

Progress of the War, page 1

“Reports of warlike movements during the week have been few and unimportant, leaving public attention free to occupy itself with the assembling of Congress, the president’s annual message, and the reports of the various departments, now more than ever important and interesting to the people from the vast war on our hands and its immense draft upon our resources.”

Official and General, page 1

“The president’s annual message has been generally read this week. The only important feature is a proposition for amendments to the constitution, authorizing payment from the national treasury for slaves emancipated by any state previous to the year 1900. This measure the president puts forward as the best means of procuring permanent peace. He does not propose to compel emancipation by it anywhere, but only offer government aid as an inducement to it.”

Original Poetry: from “The Women of ’62,” page 6

Poor seem these tasks and lame, but we shall find

Enough in them to till the noblest mind,

Warring with right ‘gainst wrong;

Rise in your might then, women of the North!

Rise in your might, and send your dearest forth,

And bid your men be strong.

Hampshire Gazette, December 9, 1862

Amherst, page 2

“The benevolent citizens of Amherst sent a good dinner to many a poor family in that town on Thanksgiving Day. S.F. Cutler and B.W. Allen were first in the good work and Whipple & Ward also gave liberally from their markets.”

The Atlantic Monthly, December 1862

“Life in the Open Air” by Theodore Winthrop (1828-1861), page 691

Beautiful, beautiful, beautiful is dawn in the woods. Sweet the first opalescent stir, as if the vanguard sunbeams shivered as they dashed along the chilly reaches of night. And the growth of day, through violet and rose and all its golden glow of promise, is tender and tenderly strong, as the deepening passions of dawning love. Presently up comes the sun very peremptory, and says to people, “Go about your business! Laggards not allowed in Maine! Nothing here to repent of, while you lie in bed and curse today because it cannot shake off the burden of yesterday; all clear the past here; all serene the future: into it at once!”

Harper’s Monthly, December 1862

Random Recollections of a Life: Charles Dickens by J.H. (Joachim Hayward) Stocqueler (1801-1886), page 79

“Of Charles Dickens whose family I had known in his boyhood, I saw but little excepting when he was in public. His incessant literary occupations, his amateur theatricals, his operations as chief agent for the execution of Miss Burdett Coutts’s charitable actions, his visits abroad, and the necessity he was under of being much at the service of strange visitors gave him but little time for tête-à-têtes with old friends. We were all surprised at the announcement which he published in Household Words regarding his domestic déménage, but the ultimate separation from Mrs. Dickens occasioned no astonishment.

Never were two people less suited to each other. He, ardent, sanguine, energetic, full of imagination and animated by powerful human sympathies; she, supine, frivolous, commonplace, passing her time between the nursery and the drawing-room.”

“Laughing Goddess of Plenty”

What was Dickinson’s attitude towards and relationship with children? According to Burleigh Mutén, children’s author and tour guide at the Dickinson Museum, the neighborhood children, including Ned and Mattie, Dickinson’s nephew and niece living next door in the Evergreens, cheered when they realized it was “Baking Day” at the Homestead. Because if they played pirates or gypsies in the orchards behind the big house, “Miss Emily” would load up a basket with cookies or slices of cake, often gingerbread, go to the window at the rear of the house (“so their mothers wouldn’t see,” explains Mutén) and lower the basket down to them with a rope.

What was Dickinson’s attitude towards and relationship with children? According to Burleigh Mutén, children’s author and tour guide at the Dickinson Museum, the neighborhood children, including Ned and Mattie, Dickinson’s nephew and niece living next door in the Evergreens, cheered when they realized it was “Baking Day” at the Homestead. Because if they played pirates or gypsies in the orchards behind the big house, “Miss Emily” would load up a basket with cookies or slices of cake, often gingerbread, go to the window at the rear of the house (“so their mothers wouldn’t see,” explains Mutén) and lower the basket down to them with a rope.

The source of this story is MacGregor Jenkins, the son of a pastor who lived across the street from the Dickinsons and was a regular recipient of Dickinson’s largesse. In a reminiscence first published in the Christian Union in October 1891, and later collected in his book, Emily Dickinson, Friend and Neighbor (1930), Jenkins described his neighbor as the children’s “laughing goddess of plenty” who offered the children “dainties dear to our hearts” and included notes that begged, “Please never grow up.” Jenkins reported that even as Dickinson became reclusive and narrowed her circle of intimates, children were always welcomed if they knocked at the back door. Mutén concludes:

They did not see their loyal friend as eccentric, but as one whose humor, generosity and loyalty was ever-present.

In an essay about the short-lived attempt to recast Dickinson as an author for children, Ingrid Satelmajer tells a different, less charming story. Dickinson’s first editors both knew the value of periodicals in spreading the reputation of writers. In his “Preface” to the first edition of Dickinson’s Poems (1890), Thomas Higginson captured the public’s imagination by casting Dickinson as a “recluse by temperament and habit,” comparing her to someone who “dwelt in a nunnery.” To counter this daunting impression, Mabel Loomis Todd began to give lectures as early as April 1891 in which she told audiences, “to children … she was always accessible.” To bolster this version of Dickinson, Todd began to send Dickinson poems, heavily edited and regularized, to children’s magazines in what Satelmajer calls

a marketing ploy gone awry.

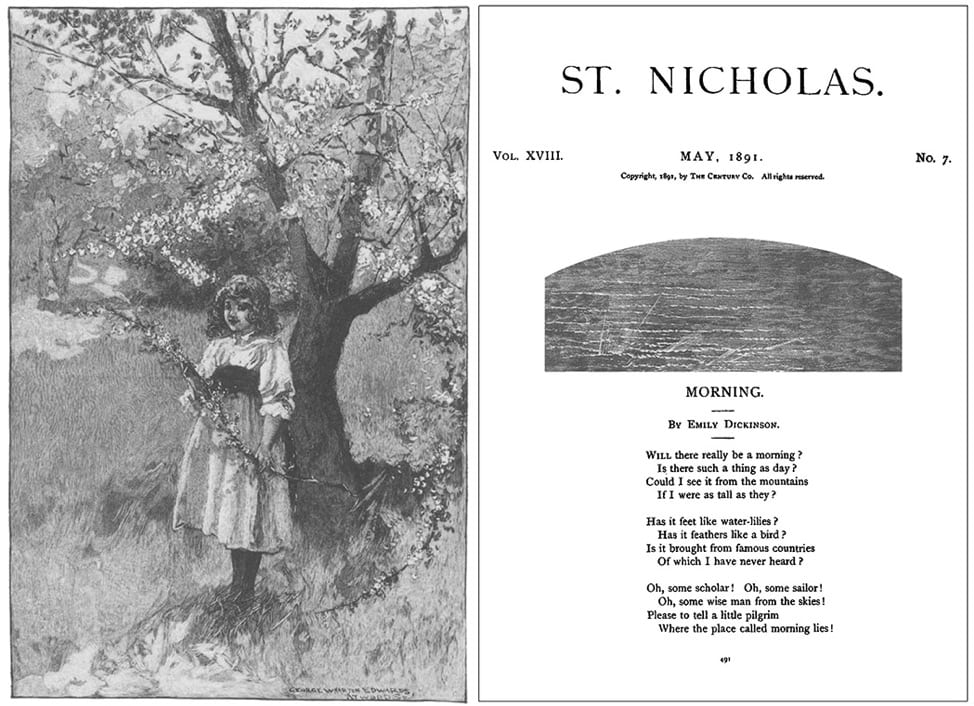

Two poems, “Morning” (“Will there really be a ‘morning?’” F148, J101) and “The Sleeping Flowers” (“Whose are the little beds” F85, J142 ) appeared in St. Nicholas, a popular and widely circulating magazine for children, which published work by such prestigious authors as William Jennings Bryant, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, John Greenleaf Whittier, Louisa May Alcott, Mark Twain, Rudyard Kipling, and Frances Hodgson Burnett.

The setting of “Morning” as the lead poem on a page opposite an illustration of “Spring Blossoms” by George Wharton Edwards, a “marquee name” at the time according to Satelmajer,

The setting of “Morning” as the lead poem on a page opposite an illustration of “Spring Blossoms” by George Wharton Edwards, a “marquee name” at the time according to Satelmajer,

gives the speaker the decided lisp of a precocious child.

This version of Dickinson served to counter the scandal that ensued when the Christian Register published Dickinson’s somewhat blasphemous “God is a distant – stately Lover -,” which compares God’s use of Christ to “woo” human souls to Miles Standish’s use of John Alden to woo Priscilla Mullins, a subject taken up in the famous poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow titled The Courtship of Miles Standish (1858). It was also good publicity for the next volume of Dickinson's posthumous poems, which would appear in 1891. Todd continued to claim Dickinson’s child friendliness, citing the publication of the two poems as proof that

[m]any of Emily Dickinson’s daintiest verses are for children,

without disclosing the radical surgery they underwent at her hands.

Still, Satelmajer concludes, there is no evidence that this campaign produced a children’s market for Dickinson. The same is not true today. There is a busy market for collections of Dickinson’s verse, curated, though not edited, for children. For example, in 2016 Susan Snively edited Emily Dickinson, the premier title in the Poetry for Kids series. The publisher’s description reads:

Each poem is beautifully illustrated by Christine Davenier and thoroughly explained by an expert. The gentle introduction, which is divided into sections by season of the year, includes commentary, definitions of important words, and a foreword.

There are also a raft of young adult novels and books that promote Dickinson to the pre-teen and teen set, especially to eager smart girls and boys like the Crossroads 7th graders, who bristled at the notion that Higginson and Todd changed so much as a dash in a Dickinson poem.

One point of attraction for them may be the many poems in which Dickinson adopts the child’s voice. Several scholars write extensively about this strategy, including biographer Cynthia Wolff, and see it as a proto-feminist critique of women’s infantilization in 19th century American culture. In 2003, Claire Raymond studied Dickinson’s child personas who speak posthumously and concluded that this strategy

is a mode of reclaiming the spent self, and perhaps also a critique of domination refracted through the prism of the voice deemed too small to be heard. There is a poignancy granted many of Dickinson’s more powerful child-spoken poems

which belies the notion that she took up the child’s voice mainly as an ironic commentary on woman’s place in culture. Rather, the poems engage a palpable erasure of the self, both as name and as body.

In Schoolroom Poets: Childhood, Performance, and the Place of American Poetry, 1865-1917, Angela Sorby examines Dickinson’s child-voice poems and links the history of her reception in the 1890s to the

discourse of infantilization and pedagogy that dominated American popular poetry of the period and, to a great extent, continues to do so today.

Reflection

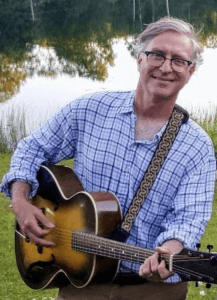

Steve Glazer

“What is freedom?” This is a powerful question for many adults; it is also a question that begins to percolate through the minds of adolescents during the middle school years. This question is also the essential question for my seventh-grade students at Crossroads Academy.

“What is freedom?” This is a powerful question for many adults; it is also a question that begins to percolate through the minds of adolescents during the middle school years. This question is also the essential question for my seventh-grade students at Crossroads Academy.

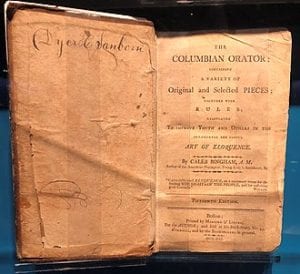

During the summer before seventh grade, the students read The Call of the Wild. As they fall in love with Buck, they gain insight into what freedom means for Jack London. As the school year begins, they contrast London’s fantasy with Frederick Douglass’s reality. They read the full text of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, by Frederick Douglass along with excerpts from Caleb Bingham’s Columbian Orator, the text that taught Douglass the rhetoric of freedom.

Later in the fall, we analyze the table of contents of Realms of Gold, our English 7 anthology. The students learn to see what is largely missing from this text: works by women. This allows us to ask an important question:

Why are women under-represented?

After a heated discussion, we begin a new unit, “Raising our Voices.” We read across seventy-five years and five genres: a political document, “The Declaration of Sentiments” by Elizabeth Cady Stanton; a work of nonfiction, “A Red Record” by Ida B. Wells; a short story, “The Yellow Wall-paper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman; a poem, “Are Women People?” by Alice Duer Miller; and an essay, the “Shakespeare’s Sister” section of Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own. Time and time and again, we return to our essential question.

What is freedom for the women gathered in Seneca Falls? What is freedom for Gilman’s nameless protagonist? What does Woolf mean when she says that for so many years, “anonymous was a woman”?

The unit concludes with a four-week unit focusing on the life and work of Emily Dickinson. We consider:

How did Emily Dickinson’s work come to appear in Realms of Gold? What are the individual and social circumstances that led to her being able to “raise her voice”? How was her unique and powerful voice edited and corrupted by three generations of editors? How does Dickinson’s room differ from Gilman’s room? Can we come to recognize that our rich understanding of Emily Dickinson’s life and work is, in fact, a fulfillment of Virginia Woolf’s dream?

Contemporary scholarship, the Emily Dickinson Museum, and www.edickinson.org enable my middle school students to work directly with Dickinson’s letters, manuscripts, envelope poems, fascicles, and herbarium. We can almost—but not quite—touch the hands that “cannot see,” the hands that seek to “gather paradise.”

Over four weeks, the students learn about Dickinson, poetry, scholarship, and literary criticism as they construct a “Letter to the World” portfolio. The portfolio includes a wide array of reading, writing, research, and record-keeping challenges. In just a few weeks, the students develop a level of intimacy and mastery that very few students (or adults) have. And after freedom, mastery is something that so many adolescents crave. The project culminates with a visit to Dickinson’s hometown on her birthday, December 10. We visit the Dickinson archive at Amherst College, we tour the Homestead and the Evergreens, we recite poems in Emily Dickinson’s parlor, and we sing “This is my letter to the World” at her gravestone.

Bio: In 1985, I graduated from Union College in Schenectady, New York, with a BA in English Language & Literature. I continued my studies at the University of Chicago, where I earned a master’s degree in English & American Literature. I am the author or editor of five books, including The Heart of Learning, Best of Valley Quest, and Questing: A Guide to Creating Community Treasure Hunts. In 2015, the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History recognized me as the “New Hampshire History Teacher of the Year.” Before joining the Crossroads Academy faculty in 2013, I directed the Valley Quest program for a decade. I have also served as an adjunct faculty member at Antioch New England Graduate School (Heritage Studies), Plymouth State University (Education), and the Center for Whole Communities (Community Facilitation). It is my pleasure and privilege to help students grapple with classic texts, learn to express their ideas with precision and eloquence, and struggle with the essential questions of English 7 and 8: “What is freedom?” and “What is justice?”

Sources

History

Atlantic Monthly, December 1862

Harper's Monthly, December 1862

Hampshire Gazette, December 9, 1862

Springfield Republican, December 6, 1862

Biography

Higginson, Thomas Wentworth. “Preface,” Poems by Emily Dickinson. Eds. Mabel Loomis Todd and T. W. Higginson. Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1890; reprint Gainesville, Fla.: Scholars’ Facsimiles and Reprints, 1967, iii, v.

Jenkins, MacGregor. “Reminiscences of Emily Dickinson.” Emily Dickinson's Reception in the 189os. Ed. Buckingham, 141-42, 141; first published in The Boston Evening Transcript, 2 May I891, 9.

Mutén, Burleigh. “Cook’s Cook: Emily Dickinson, Poet and Baker.” 10, 2017

Raymond, Claire. “Emily Dickinson as the Un-named, Buried Child.” Emily Dickinson Journal 12. 1, 2003: 107-122, 108.

Satelmajer, Ingrid. “Dickinson as Child's Fare: The Author Served up in ‘St. Nicholas.’” Book History 5 (2002): 105-142, 107, 113, 124, 127.

Sorby, Angela. Schoolroom Poets: Childhood, Performance, and the Place of American Poetry, 1865-1917. Hanover: University of New England Press, 2005.