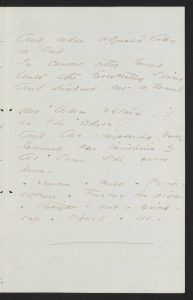

No Notice gave She, but

a Change –

No Message, but a sigh –

For Whom, the Time

did not +suffice

That she + should specify.

She was not warm, though

Summer shone

Nor scrupulous of cold

Though Rime by Rime, the

steady Frost

Opon Her +Bosom piled –

+Of shrinking ways -she

did not fright

Though all the Village

looked –

But held Her gravity

aloft –

And met the gaze – direct –

And when adjusted like

a seed

In careful fitted Ground

Unto the Everlasting Spring

And hindered but a Mound

Her + Warm return, if

so she + chose –

And We – imploring drew –

Removed our invitation by

As + Some She never

knew –

+remain +could +Petals •

softness +Forebore her fright

+straight – good – quick –

safe +signed +Us

Link to EDA manuscript. Originally in Poems: Packet XXX, Fascicle 38, ca. 1863. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Unpublished Poem (1935), 124, with the alternative for line 9 adopted.

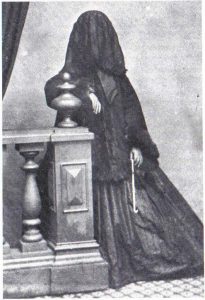

This poem illustrates Dickinson’s fully spiritual meaning of spring. It describes the death of a woman, who expired almost imperceptibly, “no notice … no message, but a sigh.” In the poem, the dead woman persists through summer and winter. It is not until stanza four that she encounters spring and is transformed. She is “adjusted like a seed / In careful fitted Ground / Unto the Everlasting Spring” and her “warm return” comes with a flurry of variants: “straight,” “good,” “quick,” “safe.” But, in what way is she returned? Is she resurrected? As an elect soul going to Heaven? In the minds and memories of her friends? The last stanza is a study in ambiguity.

In last week’s post, in relation to the death of Frazar Stearns, we discussed Dickinson’s focus on the way of death, especially a person’s last words, attitude, and demeanor as offering a glimpse of the character of immortality.

Diana Fuss compares Dickinson’s poetic treatment of these last moments of death to her contemporaries, women poets like Helen Hunt Jackson, Lydia Sigourney and Frances Harper, who all

exploit the personal and political potential of last words to command attention and to provoke response.

Dickinson, she finds,

uses the deathbed address not to claim agency but to relinquish it.

These poems, like “No notice gave She,” emphasize

the radical privacy of death. … Dickinson’s dead protect their secrets.

Jesse Curran takes a different tack, seeing Dickinson’s allusions to breath (here, the “sigh”) as a sign of her meditative poetics, which Curran links to

recent critical developments in sustainability studies, as well as to the global-ecological theory that underlies its emergence

and focuses on air as the medium connecting us all.

Sources

- Curran, Jesse. “Transcendental Meditation: Sustainability Studies and Dickinson’s Breath.” The Emily Dickinson Journal, 22, 2, 2013, pp. 86-106, 86, 93.

- Fuss, Diane. “Last Words.” ELH 76 (2009) 877–910, 883-84.