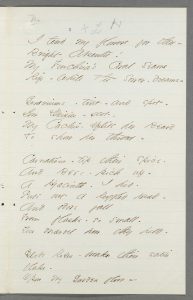

I tend my flowers for thee –

Bright Absentee!

My Fuschzia’s Coral Seams

Rip – while the Sower – dreams –

Geraniums – tint – and spot –

Low Daisies – dot –

My Cactus – splits her Beard

To show her throat –

Carnations – tip their spice –

And Bees – pick up –

A Hyacinth – I hid –

Puts out a Ruffled Head –

And odors fall

From flasks – so small –

You marvel how they held –

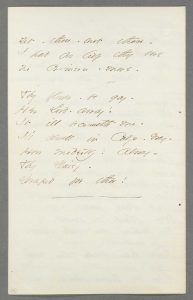

Globe Roses – break their satin

flake –

Opon my Garden floor –

Yet – though – n not there –

I had as lief they bore

No crimson – more –

Thy flower – be gay –

Her Lord – away!

It ill becometh me –

I’ll dwell in Calyx – Gray –

How modestly – alway –

Thy Daisy –

Draped for thee!

Link to EDA manuscript. Originally in: Packet VI, Fascicle 18, written in ink, dated ca. 1862.

First published in London Mercury, 19 (February 1929), 353-54. Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

Richard Sewall connects this poem with the Master Letters in his extended consideration of Samuel Bowles as the man Dickinson addressed as “Master.” Instead of being dated to “early 1862,” he speculates that it might have been written soon after Bowles left for Europe in April, recording Dickinson’s sadness at the absence of her “Lord.”

Dickinson developed an extended discourse on flowers in her writing. This is not surprising, since, as Paula Bennett observes, most middle-class women of the time occupied themselves in care and cultivation of flowers. Dickinson’s father built a greenhouse off his library in which she cultivated exotic specimens (which has now been reconstructed at the Homestead), and she and her mother and sister worked in their gardens outdoors in summer.

Dickinson often included a single bloom in the many letters she wrote, as in Letter 253 to Mary Bowles discussed above. Flowers brought her close to heaven; in a letter to a friend, she wrote, “Expulsion from Eden grows indistinct in the presence of flowers so blissful, and with no disrespect to Genesis, Paradise remains” (L 523). Bennett finds approximately 400 references to flowers or their parts in Dickinson’s poems, and notes the importance of Dickinson calling herself “Daisy.” She also calls attention to the figurative use that Dickinson and other writers of the period made of flowers, to encode

references to poetry and the poetic process, to individuals and generic human beings, to Jesus and the soul, to Eden and bliss, and, perhaps most important, to woman and the female genitalia, so these images substantially contribute to the notorious ambiguity of her writing.

Cynthia Wolff connects this poem to the love poem discussed previously, “Doubt me! My dim companion!” (F332A J 275). Here, she says, “when the beloved is gone, the speaker’s garden vividly reflects her sexual frustration.”

Sharon Harris goes further:

What is particularly confusing in this poem, which suggests both allurement and rape, is that ‘Her Lord’ is away; he is endowed with an almost omniscient ability to violate her dream state through a silence of removal.