UNGULATING : An Artist’s Statement

The stylistic dehumanization of characters in graphic novels is a narratological device that’s seen an upsurgence in recent use. Works such as Art Spiegelman’s Maus were luminaries in this regard: lending human characters, that we know to be human, anthropomorphic designs, that conceive of them as otherwise. The device can greatly increase a

work’s iconography. But beyond memorability, it can wordlessly encapsulate narrative elements, including but not limited to: a conflict central to the narrative ( Maus ’ titular mice are Jewish, and its predatory felines are Nazis); a pathology experienced by an unreliable narrator (Jean-Philippe Stassen’s Deogratias ’ traumatized protagonist, who comes to believe himself a dog, is portrayed as one); and/or a temperament belonging to a character. Inio Asano’s Goodnight Punpun renders its main character a stick-legged, birdlike caricature. When presented with this species, we (the audience) perceive skittishness and fragility. Despite being a silent character — it so happens that another major narrational decision on Asano’s part was to never have Punpun outright speak — we get a durable enough impression of the character, merely from the split-second impression his ‘dehumanized’ portrayal grants us.

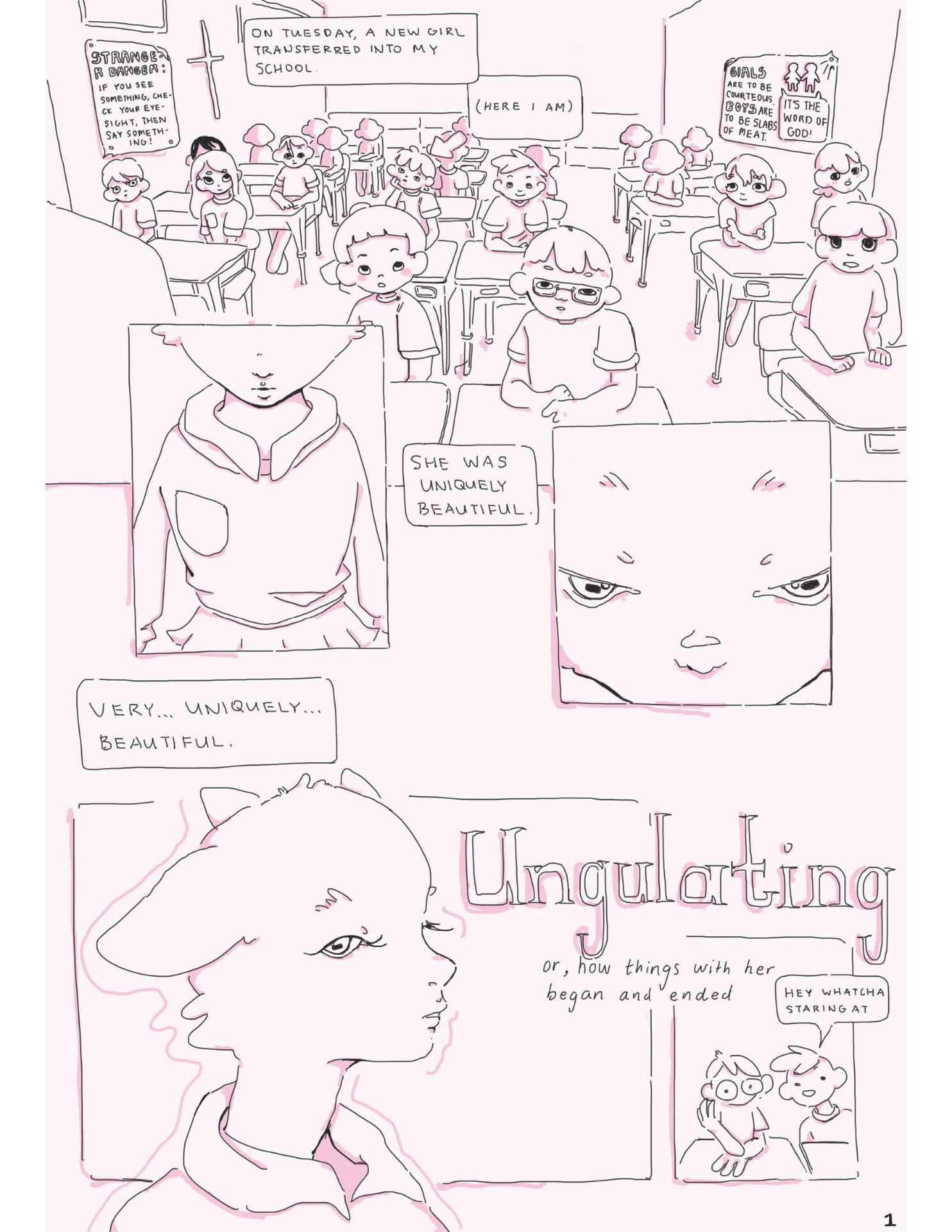

This comic is a venture into that stylistic dehumanization, and how it can be used to build a narrative. I work with one character, specifically: the new girl at the narrator’s Christian private school. She is described as “uniquely beautiful,” in that she possesses non-anthropomorphic features conventionally ascribed to beauty. But, in the eyes of the narrator, she

is … a goat.

At first, this is an inexplicable design choice. There is a suspended ambiguity as to whether ‘Phia’ genuinely appears this way, or takes on this ‘satyrical’ form for our unreliable narrator alone. The latter is implied to be true. Page 2

gives us a glimpse of Phia’s prospering social life: she laughs among friends, documents her companionship on social media, and is pestered for invitations to a supposed family mansion, which she declines, smiling good-naturedly. Nowhere in the dialogue is there a reference to her floppy, white ears, to the fur clinging to her cheeks, to the protruding nubs of

horns atop her head. It is only the unnamed protagonist who sees her the way the readership sees her. This, in itself, builds suspense. Surely, the illustrator did not just arbitrarily single out a character to be a goat?

No, she did not: this strange design choice becomes increasingly related to the strangeness that the narrator sees in Phia. The narrator, after all, has a Christian upbringing — assumed to be an fundamentalist one. Goats aren’t kindly received by a preponderance of this subgroup; they are more so feared. The parable of the sheep and the goats, from Matthew 25:31-34, reads: “When the Son of Man comes … he will separate people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats. And he will place the sheep on his right, but the goats on his left.” This is a scripture that dissuades listeners from resisting the pull of Godliness; it configures the pious as sheep (benevolent), and the infidels as goats (malevolent, untrustworthy). On page 3, Phia begins dating the narrator — a flight of fancy that confuses him,

profoundly, and begets a one-sided conversation between them at a fast food restaurant. Phia notices the confusion. She explains that it is precisely his plainness that ‘attracts’ her to him. She does so unkindly. “You don’t attract attention,” she monologues, while extricating a tomato from her burger. “You don’t have enough friends to be popular, but you have enough to avoid seeming a perverted loner.” The boy, in Phia’s goatly eyes (note the shape of her pupils), is “as simple as the molecules that comprise you.” She says this while tossing aside her tomato-slice with finality. It is discarded, juices

flying, before the narrator. This particular panel’s action-dialogue synergy suggests an unnerving development. To Phia, the main character is as disposable as an unpopular burger ingredient. They can both be rid of with nary a fissure in the girl’s emotional exterior. His ignorance — as to how lucky he has it, that he need not rely on an engineered likability to

maneuver through their world — makes Phia “hate you a little.” Soliloquy finished, and tomato excommunicated, the meal passes in silence. The narrator cannot stop sweating cartoonishly plump bullets.

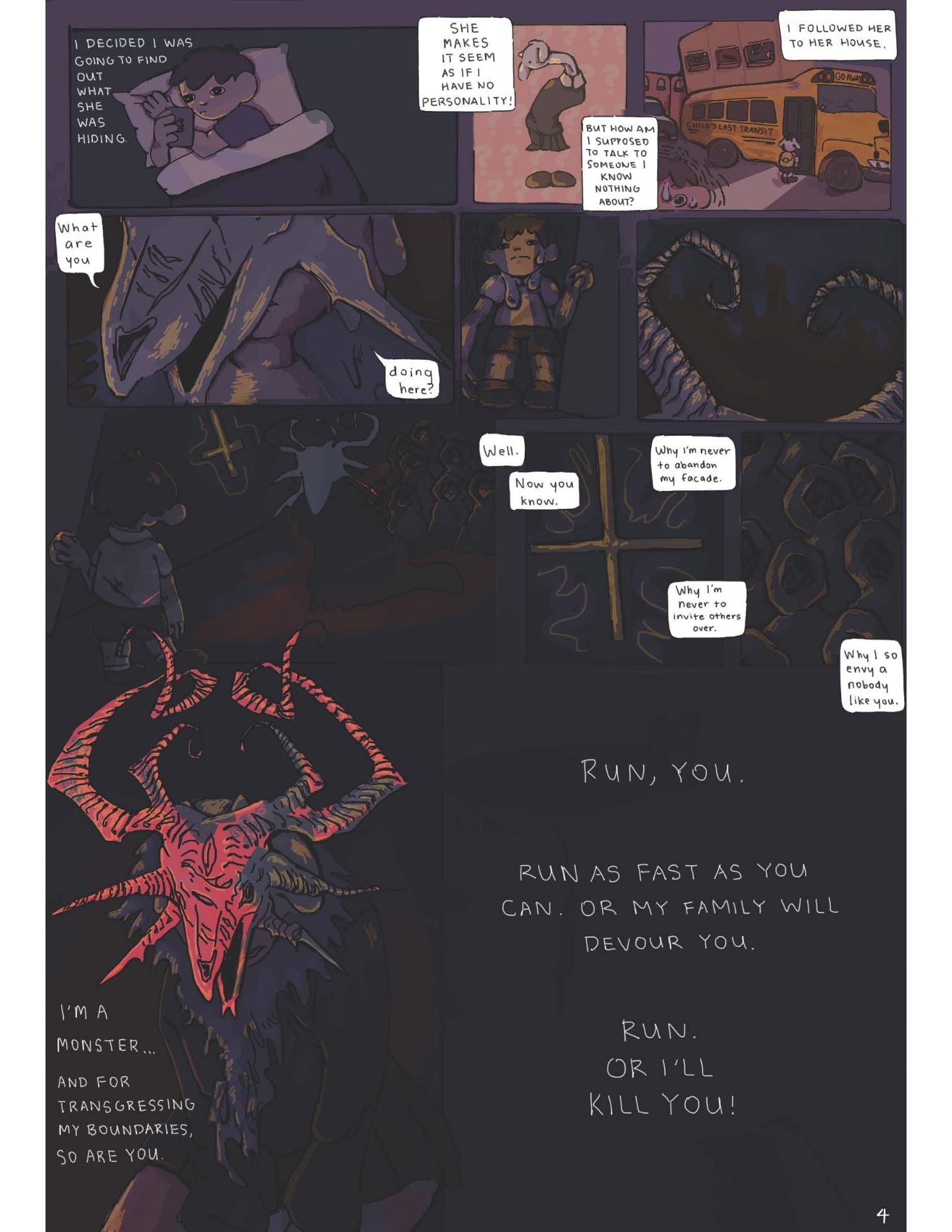

As we arrive upon the final page, it has been established that Phia’s stylistic dehumanization as goat is intertwined with two out of the three formerly mentioned motives for this device. (1) Conflict : Phia appears to experience some instance of this in her home life, which has forced her into privacy, and toward a pretense of goodwill. (2) Pathology : The narrator begins to recognize this pretense as farcical. His initial distrust has cemented itself further. Fear has gripped his heart. As for (3) temperament : this is to be uncovered. Until now, Phia’s goatliness is a result of the narrator’s feelings

about her. It remains to be seen whether her “unique beauty” appears in the beholder’s eye alone — or if it truly suggests about her , and not just about how she is seen .

The revelation on page 4 offers clarity. The narrator, as befitting of any fool in a horror movie, trails the threat, and trails her home, unprepared for what he interrupts: a ceremonial Satanic cult procession, with Phia at the center.

Bestowed, unhappily, with a skeletal goat head and a skinned fur hide, the girl sits in a pool of blood. Earlier hints begin to converge. The ‘danger!’ branding on the cup of fries, and the inverted crosses on the takeout bag (pg. 3). Phia’s social media icon; the enigma that is her family; the rumors of her relocations; her reluctance to welcome visitors to her home (pg. 2). And, perhaps most unsettling, the classroom poster from the very first panel, which declares “boys” to be mere “slabs of meat.” Even the rightside-up cross on the left wall fulfills more than shallow decorative use — it is eventually juxtaposed with the inverted one, glinting, in Phia’s home (pg. 1). At last, the temperament motive to Phia’s stylistic dehumanization is clear. For Phia is frivolous, girlish shorthand for Baphomet , the Sabbatical Goat. He is a pagan idol that Satanists will use to deride fundamentalists for their concoction of imaginary enemies, for their persecution complex fueled by fantasies. Here, as is the case in most comics that anthropomorphize, it is difficult to draw a perfect analogy. The threat that Phia presents is not strictly imaginary, especially considering the ambiguous way the comic ends (did the narrator make it out alive, or is the fade-to-black suggestive of a gruesome fate?). Yet the comic allows for an alternative assignment of blame: that, had the narrator simply respected Phia’s privacy, the conclusion would have been different.

I chose to explore the subject of stylistic dehumanization because of how polarizing it can be. The anthropomorphization of factually human characters is contentious, and, as proven, can breed multiple interpretations of the narrative fortified by the device. Spiegelman, for instance, was accused of trivializing the Holocaust for his mouse/cat depictions of its victims and perpetrators. His work has also been criticized for presenting racial conflict as phenotypical: does speciefication only further racialize that conflict? Stylistic dehumanization, after all, is dehumanization. Caricatures

can easily reinforce normative biases. The device is a double-edged sword: wielding it requires skill, and I wanted to see if I was up to the challenge.

I believe, overall, the comic was a success. It demonstrated the narratological effect of my chosen device: the representation of a girl as a goat, as buildup to the reveal that she is the figurehead of a Satanic cult. More precisely, it

explores a subset of narratology known as narrative empathy . Researcher Suzanne Keen, in her “ Living Handbook of Narratology ,” categorizes ingroup empathy (the ability of a demographic to relate to its own representation) as ‘bounded strategic empathy,’ and outgroup empathy (the ability of one to relate to the representation of a demographic they do not belong to) as ‘ambassadorial strategic empathy.’ Here, the latter applies: how, in spite of animalistic portrayals, mankind can still relate to these ‘ambassadorial’ comics. UNGULATING does present a unique case, as only the antagonized party is dehumanized. However, perhaps by virtue of being the only three-dimensional character in a four-page comic, I do find Phia sympathetic. Laced within her lifetime of concealment, and deception, is a resounding unhappiness at being unable to enjoy her adolescence. Hence the concoction of envy and resentment at the narrator’s atomically simple life; hence the

downturned corners of her mouth in the penultimate panel, almost as if she is on the verge of tears.

I cannot force you, the reader, to empathize with a literal Satanist. However, I do hope that my comic has imparted upon you a more holistic understanding of stylistic dehumanization.

©2020 Michelle Chen