Merry and mirthful songs repeatedly caper through “As You Like It”, with blithe, bucolic lyrics that suggest what the modern ear can no longer hear. Whatever melodies, tones, and textures Shakespeare envisioned have mostly evaporated under the sweep of time, and an unaided imagination tends to flop short in grasping the succinct levity of these songs. The thumping, pounding rhythms of modern pop and rap music are a poor mental substitute for whatever non-textual effects Shakespeare desired in his musical insertions, and so the task of replaying Shakespeare is not an immediately easy one.

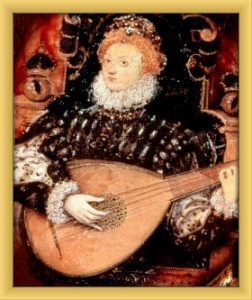

Music was ubiquitous in Elizabethan times (as critic H.B. Lathrop attests). Music was undergoing a dramatic vitalization and expansion, or in more historical terms, a Renaissance. Not only was it proliferating in the uppermost classes, as one would expect, where the courtly paid insatiably for professional musicians, but this penchant for tune appears to have percolated into Elizabethan culture. Singing likely was a pastime enjoyed by many, and Shakespeare himself frequently records the voices of common men in song. Several of Shakespeare’s drinking songs were riffed from real songs that could probably grated the ears of passersby at odd hours of the day. Street and tavern performers filled the void of then-extinct minstrels popularizing the sound of fiddles, lutes, recorders, and small percussion instruments that would have been very familiar to Shakespeare’s audience.

Music evolved into a stationary art with an expanding array of innovated instruments predating modern conceptions of the orchestra. The first keyboard instruments arrived during the Elizabethan period- most famously the harpsichord. A variety of lute, trumpets, horn augmented the volume capabilities of the theater performers, and music became an asset for Elizabethan theaters and an attraction for their music craze of the era.

Bowing to this demand, the King’s Men employed a functional troop of musicians. A common arrangement, known as a mixed consort, consisted of Flute, treble viol, bandore, lute, cittern and bass viol and was a popular form by the late 1500’s. But a range of other compositions and sound effects textured Shakespeare’s plays to an extent that curiously portends the soundtrack discipline in modern movie production. Notably, musicians hid under the stage to filter out a hollow, distant sound to the audience (most notably in the haunting moments of Macbeth).

Still, ascertaining the musical form of exact songs remains tricky. The pastoral tunes of “As You Like It” might have employed rustic instruments like the pipe (a basic flute instrument) and tabo (a small drum) to augment the sylvan texture of the play. The company might have embraced the flare or elegance of the newer instruments as a stylistic choice. Regardless, the verse’s musical structure would be redundant, highly structured, and probably quite familiar to the aural sensibilities of the audience.

The subtly aforementioned H.B. Lathrop devotes an entire essay to the potential dramatic purposes of song in Shakespeare’s drama. The foremost, though, seems to rely on the integral repetition of Elizabethan folk tunes; the circularity of the melodies, as well as their attached lyrics, arrest the propellant motion of Shakespeare’s drama, and accentuate the exaltation, or sometimes the dejection of the momentary, to freeze the emotional achievements of Shakespeare’s undulating plots. This effect is easily disregarded when reading the plays. In fact, an uncomprehending eye almost skips over these brief inactive blips. But rediscovering the vibrancy and cultural clout of music in the Elizabethan era, a reader at least understands that these songs were crowd pleasers, and crucial elements to the spoken drama.

(information on music in Shakespeare’s time, as well as its dramatic purposes can be found in H.B. Lathrop’s essay “Shakespeare’s Dramatic use of Songs.” Follow specific links for information on instruments and ensembles.)