In Shakespeare’s time, English was in a particular state of flux. The lexicon was flurrying with pronunciations, dialects, spellings, and grammatical, unchecked by mass literacy and printing that current readership presumes. A modern likely won’t see in the innocuous, slightly archaic print of a Shakespeare script that Shakespeare’s pen transcribed the frenetic phonetics of Renaissance-era English. And while mediocre actors might feign a haughty British accent, or prolong syllables as though Shakespeare intended his plays for a race of droning sloths, really such sounds would be as foreign to Shakespeare’s audience as they are to the modern layman.

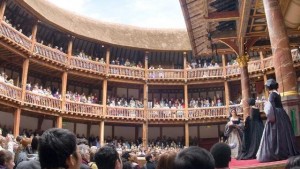

Though the pursuit of meaning and clarity is natural to Shakespearean scholarship, the attempt to construe Shakespeare’s plays in their original pronunciation (“OP”) is quite recent. Helmed by linguist-actor David Crystal, Shakespeare’s Globe theater (a modern reproduction) staged “OP” productions of “Romeo and Juliet” in 2004, with the assumption that replicating the Elizabethan tongue would elucidate the language and bolster the authentic experience (though this claim itself has been fiercely contended). Gratified audience members described the tone as “casual” “rustic,” and “earthed”– a far departure from the highfalutin quavering of the most mawkish Shakespeareans. Though such evolution might seem inevitable to 400 years of lingual development, the Renaissance was an epoch of distinct transformation, during which Early Modern English emerged. (Crude history warning:) The burgeoning trade and interactions between increasingly prosperous and competent European societies stimulated exchange in language, as it has famously done in the arts. True to the neoclassical affinity of the day, Early Modern English absorbed Greek and Latin words and roots at impressive rates. Beneath this importation, the vernacular variety was exceptional. The courtly, the legal, the peasantry, all spoke according to their delineated positions. Colloquial accents and vernaculars were rampant before mass literacy standardized conventions or cultural hegemony suppressed peripheral varieties. This lingual frenzy, scholar Laura Lodewyck argues, conceived a society particularly attuned to the shrewd, deft variations and strains of Shakespeare’s language: “the practice of reading aloud and reciting verse developed acute inner ears that could appreciate sonic effects which are lost on moderns…Elizabethan aural sensitivity led to delight in wordplay of all kinds, repartee, double entendre, puns, and quibbles”. Though modernity bristles at being excluded from any period of time or context, it seems that Shakespeare was immersed in an era where his diverse, polyphonic characters would have resonated especially with an audience and language commensurately diverse.

Any reader who has reached this far no doubt thirsts for some specificity. Defining a lexicon is a vast business, a matter of independent study to linguists, literary historians, actors and buffs alike. But below are some fecund examples to tantalize an understanding of Middle English’s ambiguities and complexities, from David Crystal himself (the name is a byword for OP studies, for anybody interested). The example of “thou” is so iconic that it’s naturally fluent in modern English, but is often falsely simplified as a formal alternate to “you”. In Old English, “thou” was singular and “you” was plural, and by Shakespeare’s time, you had actually become the more respectful, formal alternate to thou. The verb conjugations “-th” and “-s” both existed in Early Modern English, and “-th” had already come to signify a more august tone. Shakespeare twists the variations deftly to fit meter and represent different vernaculars. Though the European practice of pronouncing final -e’s was already fading from English, the vowel still persisted, selectively, in the past tense of verbs (-ed). While the decision to selectively add the additional vowel may be partly practical, it is also might invoke different voices and tones suiting to Shakespeare’s manifold characters.

Ultimately, the admonition here is to resist accepting the static inertia of printed words, as is the natural impulse for the medium. Though grasping the intricacies of Early Modern English is a quest probably disproportionate to a beginner’s first excursions with Shakespeare, carefully heeding the differences in diction, tone, and language is not. The voices behind the lines may have contained another peel of significance that time and a less than astute eye might waste.

(Basic OP information derived from originalpronunciation.com

Try searches on OP or David Crystal for further results)