Although their modern definitions are more distinct from each other, “fantasy” and “fancy” could more or less be used synonymously in Shakespeare’s era. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, both could mean “the process, and the faculty, of forming mental representations of things not present to the senses” (See definition 4a: OED – Fantasy). Yet at the same time, both words have a variety of underlying meanings that invoke a deeper understanding of Shakespeare’s social commentary.

The first instance of the word “fantasy” in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream appears in Egeus’s complaint to Lysander about Hermia: “Thou hast by moonlight at her window sung / With feigning voice verses of feigning love, / And stol’n the impression of her fantasy” (1.1.30-32). The most basic definition of “fantasy” in this usage is one synonymous with “fancy,” meaning Egeus condemns Lysander for stealing Hermia’s admiration and love. But Shakespeare also invokes another definition of “fantasy” by its use in this context: “A supposition resting on no solid grounds; a whimsical or visionary notion or speculation” (See definition 5a, OED – Fantasy). In this sense, Egeus states that Hermia’s love for Lysander is a delusion, “resting on no solid grounds,” impressed upon her by Lysander. Egeus, the father figure, believes Hermia’s love could — and should — be determined by her father. In contrast, a non-patriarchal understanding of Hermia’s fancy is one in which it is not something that can be stolen. Instead, it is self-determined. Does this mean Shakespeare believed love is only a fantasy, “whimsically” constructed in our minds, but not actually real? Did he believe one’s “fancy” was determined by a father, a lover, or the juice of a magical flower?

The best answer to these questions perhaps lies in contrasting settings: the Athenian court versus the fairy-filled forest. With Athens as a backdrop, “fantasy” or “fancy” is defined as inherently controllable (for example, a daughter’s fancy is controlled by her father). For instance, Hermia remarks in the Duke’s palace in Athens: that “thoughts, and dreams, and sighs” as well as “wishes, and tears” are “poor Fancy’s followers” (1.1.154-155). Here, “fancy” is personified into a monarch, and as Brendan states in his article “Fantasy: The Underlying of Reality”, it “enslaves its followers, dooming them to a life lived outside the reasonable and rational confines of normal life” (Fantasy: The Underlying of Reality). Like Egeus’s usage of “fantasy” as discussed previously, Hermia’s usage of “fancy” invokes an image of imagined, “arbitrary preference” (See definition 8a: OED – Fancy). As a result, “love,” is able to be manipulated and determined by external forces and beings.

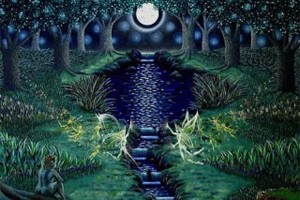

The forest setting takes the manipulation of one’s “fantasies” or “fancies” to a magical extreme. Oberon and Puck’s ability to control Demetrius and Lysander’s “fancies” parallels Egeus’s (claimed) ability to decide Hermia’s true love. The mythical, mysterious aspects of the forest and the fairies only emphasizes the absurdity of the notion that one’s “fancy” can be determined by someone other than oneself. Oberon’s successful plan to make Titania “full of hateful fantasies” (2.2.258) is purposefully comical, highlighting that only in a mythical setting with mythical creatures would this idea make any sense. As a result, Shakespeare argues that one’s “fancy” can only be determined by one’s own self.

Lastly, it is worth mentioning that both “fancy” and “fantasy” exist in verb form (OED – Fancy (verb) and OED – Fantasy (verb)), but Shakespeare fails to use these forms throughout the entirety of the play. This only accentuates Shakespeare’s argument of control and manipulation of one’s “fancy” or love in a patriarchal society. With Egeus or Theseus involved, Hermia has no choice, no capability for self-determined action when it comes to choosing who she wants to married. By using “fancy” and “fantasy” solely as nouns, Shakespeare emphasizes how they are manipulated throughout the play.