The idea that Shakespeare grapples with the idea of “aesthetics” is anachronistic—the term was first used in its modern sense in 1735, over 100 years after his death (“aesthetic, n. and adj.”). But looking back on A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Hugh Grady convincingly locates the play within a framework of a number of philosophical stances on this issue. Aesthetics, the philosophical study of beauty, art, and taste, arose as a concern for philosophers in the late Enlightenment and early Romantic periods, notably Emmanuel Kant. Kant, as well as the New Critics and Northrop Frye, believed, in short, that one must look at art or beauty through a ‘disinterested’ lens which privileges art and aesthetic objects as separate from the rest of the world. These critics run against most poststructuralists and Marxists, who analyze the ideological, political, and materialist ancestry of art objects.

Grady, however, finds a few critics who exist between these two opposing spheres of thought to be useful in understanding Shakespeare’s own implicit stance on aesthetics. Critics such as Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno and Ernst Bloch argue that although art and the ‘aesthetic’ relate to the outside world, they nevertheless exist independent of the society that created it. In other words, they believe in an “impure” aesthetic, one tinged with the markings of society, ideology, and sexual desire.

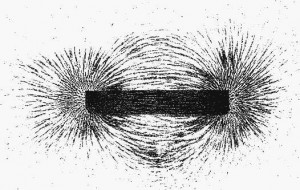

Grady quotes Adorno as saying, “Art is related to its other as is a magnet to a field of iron filings” (280).

How does this idea of an ‘impure’ aesthetic manifest in the action and poetry of A Midsummer Night’s Dream? Grady sees the play as a “meta-aesthetic drama” in which Shakespeare presents a dreamlike, aesthetic world in order to comment on the nature of literal art, beauty, and dreams (Grady 278). He finds this ‘meta’ aspect of the play in not only the workmen’s production of Pyramus and Thisbe, but also, and maybe more importantly, the lyrical and imaginative fairy realm, presided over by Oberon and Titania.

Shakespeare’s rendering of the forest aptly demonstrates ‘impure aesthetics’ because it contains both supernatural and human elements. The intensely lyrical description of the forest and its inhabitants, as well as Shakespeare’s introduction of supernatural magic, make the forest an imaginative and thus aesthetic ground: “Oberon and Titania control the forces of nature and live in a fairy paradise of rare beauty distinct from the human world and with its own poetic stylization” (Grady 282). As Grady notes, however, the fairies are nevertheless humanlike, succumbing to human emotions such as desire, greed, and jealousy that connect the forest to Theseus’ Athens and play predominantly in that aesthetic realm. This paradoxical relationship between the real and the unreal, the material and the supernatural, adequately mirrors the relationship that the real world has to the aesthetic realm in “impure aesthetics”.

So the fairy realm resembles the “impure aesthetic”. So what? How does Shakespeare show that the “impure aesthetic” is even a good or useful way to understand art?

Grady argues that Shakespeare saw the aesthetic realm as a space in which humans can resolve their internal issues and achieve a sense of harmony, just as the Athenian lovers use the magic of the forest to resolve their personal issues. The “impure aesthetic,” like the forest, solves issues not through ideology but through the creation of an imaginative utopia. Grady argues that the forest, more specifically the dream that the characters remember their experiences of the forest as, represents a space in which the characters can “clarify our unmet needs by conceptualizing their fulfillment in an artifactual, unreal form” (Grady 278). Thus, Shakespeare presents an aesthetic sphere that, through imagination rather than ideology, actually has the ability to expose real world problems.

Though the “purposeless purposiveness” of “impure aesthetics” is a rationally incompatible position, in a postmodern sense, this is ironically quite appealing, because it allows one to view art holistically and without the dogma that accompanies either end of the Kantian/ideological spectrum (Grady 302).

Works Cited

“aesthetic, n. and adj.” OED Online. Oxford University Press, June 2015. Web. 7 July 2015.

Grady, Hugh. “Shakespeare and Impure Aesthetics: The Case of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” Shakespeare Quarterly Vol. 59. Number 3. Fall 2008: 274-302. Project MUSE. Web. 7 July 2015.

Shakespeare, William. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The Complete Pelican Shakespeare. Ed. Stephen Orgel and A.R. Braunmuller. London: Penguin Books, 2002. 258-284. Print.