4. Impact on the Theatre

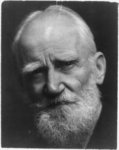

While many commend Duse as a feminist icon before the era of World War I, she had a rather ambivalent take on feminist issues and felt that women should be allowed to develop fully as an individual. This attitude relates to the role of Nora Helmer, which led Duse to becoming such a feminist icon, along with her portrayals of Hedda in Hedda Gabler and Ellida in The Lady from the Sea.[1] While taking on these important roles, Duse established herself as a businesswoman of her own company in the world of theatre. Duse enacted a great influence on many male writers and performers, including but certainly not limited to Gabriele d’ Annunzio, Luigi Pirandello, George Bernard Shaw (picture left), James Joyce, Lee Strasberg, and Sanford Meisner.[2] By legitimizing her acting style through depth and her dedication to her craft, she was legitimizing women’s thought, desires, feelings, and experiences through the stories she told on the stage. If theatre is a slice of life, then the slice Duse shared empowered women throughout the world.

While many commend Duse as a feminist icon before the era of World War I, she had a rather ambivalent take on feminist issues and felt that women should be allowed to develop fully as an individual. This attitude relates to the role of Nora Helmer, which led Duse to becoming such a feminist icon, along with her portrayals of Hedda in Hedda Gabler and Ellida in The Lady from the Sea.[1] While taking on these important roles, Duse established herself as a businesswoman of her own company in the world of theatre. Duse enacted a great influence on many male writers and performers, including but certainly not limited to Gabriele d’ Annunzio, Luigi Pirandello, George Bernard Shaw (picture left), James Joyce, Lee Strasberg, and Sanford Meisner.[2] By legitimizing her acting style through depth and her dedication to her craft, she was legitimizing women’s thought, desires, feelings, and experiences through the stories she told on the stage. If theatre is a slice of life, then the slice Duse shared empowered women throughout the world.

In terms of primary materials to examine, Duse remains mysterious. The lack of an autobiography serves to make the legacy of the real Duse elusive.[3] Scholars must rely on her letters, annotated scripts, and the reviews of her work to encapsulate her character and impact. An example of this is characterized with the comparisons of Duse to Sarah Bernhardt (pictured right). While considerable criticism surrounds both of these rival actresses, by the end of her career, Duse had attained primacy in the theater according to the writings of George Bernard Shaw and Arthur Symons, the latter of which had declared Duse the greatest actress in the world.[4] Bernhardt had remarked that Duse never claimed a character for her own, but amid criticism such as this, Shaw said the opposite, “that Bernhardt never entered into her characters, but rather “substituted herself” for them.”[5]

In terms of primary materials to examine, Duse remains mysterious. The lack of an autobiography serves to make the legacy of the real Duse elusive.[3] Scholars must rely on her letters, annotated scripts, and the reviews of her work to encapsulate her character and impact. An example of this is characterized with the comparisons of Duse to Sarah Bernhardt (pictured right). While considerable criticism surrounds both of these rival actresses, by the end of her career, Duse had attained primacy in the theater according to the writings of George Bernard Shaw and Arthur Symons, the latter of which had declared Duse the greatest actress in the world.[4] Bernhardt had remarked that Duse never claimed a character for her own, but amid criticism such as this, Shaw said the opposite, “that Bernhardt never entered into her characters, but rather “substituted herself” for them.”[5]

Her worldwide renown was reinforced by touring through Russia in 1891. Her artistry impressed Anton Chekhov (pictured left) so much that he is believed to have modeled Madame Arkadina in his play The Seagull after Duse.[6] Her influence would have therefore flowed directly into the famed Moscow Art Theatre and led to the worldwide revolution in acting techniques that was to come. Duse, however, was truly a marvel of her time. “From 1884 to 1924,” Eleonora Duse “stood for the most potent magic of which the theatre is capable.”[7]

Her worldwide renown was reinforced by touring through Russia in 1891. Her artistry impressed Anton Chekhov (pictured left) so much that he is believed to have modeled Madame Arkadina in his play The Seagull after Duse.[6] Her influence would have therefore flowed directly into the famed Moscow Art Theatre and led to the worldwide revolution in acting techniques that was to come. Duse, however, was truly a marvel of her time. “From 1884 to 1924,” Eleonora Duse “stood for the most potent magic of which the theatre is capable.”[7]

Duse’s initial retirement was highly praised as she was stepping away from her work at the absolute height of her career in 1909. While her comeback in 1921 did not bring the Duse of the past with it, she could not undo the legacy that she had already created through her work in the Italian theatre.[8] However, her second career was not a failure in the financial sense, Duse continuously thrilled audiences, but she failed on her own level to fully attain the characters she sought to create at this time. By the year of her death, Italy was at a crossroads under to leadership of Mussolini. While the state exploited her legacy as an example of Italian pride, her contemporaries in the theater worked diligently to establish a legacy akin to the work Duse had done in her career. These contemporaries struggled to show how Duse had made the theatre grander and yet purer in her attempts to reunite theatre with her religion.[9] They struggled to show her impact in terms of art and not solely in terms of her nationality, as the rising political scene in Italy was keen to do.

- Re, Lucia. “Eleonora Duse and Women: Performing Desire, Power, and Knowledge.” Italian Studies, vol. 70, no. 3, 2015, 351.

- Re, 347.

- Re, 355.

- Bassnett, Susan. “Duse, Eleonora Giulia Amalia (1858–1924).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Longman, Stanley Vincent. “Eleonora Duse’s Second Career.” Theatre Survey, vol. 21, no. 2, 1980, 167.

- Fisher, James. “Duse, Eleonora.” American National Biography Online, Oxford Unniversity Press, 2000.

- Le Gallienne, Eva. The Mystic in the Theatre: Eleonora Duse. Ambassador Books, Ltd., 1966. 3.

- Longman, 165.

- Mather, Christine C. “The Political Afterlife of Eleonora Duse.” Theatre Survey, vol. 45, no. 1, 2004, 41.

Photographs: Above right: George Bernard Shaw, 1856 to 1950. [No Date Recorded on Caption Card] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <https://www.loc.gov/item/2002715763/>. Right: [Sarah Bernhardt]. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <https://www.loc.gov/item/2005685633/>. Below left: [Anton Pavlovich Chekhov, 1860 to 1904, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing right]. [No Date Recorded on Caption Card] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <https://www.loc.gov/item/2005680061/>.