3. Acting Style

“Act? What a hideous word! If it was just a matter of acting—I feel I have never known how to act! Those poor women in my plays have entered so far into my heart and into my mind that while I am doing my best to make my listeners understand them, as if I wanted to comfort them . . . it is they who have, little by little, ended in comforting me!” – Eleonora Duse

Eleonora Duse changed the world of acting. In her early career, there was minimal rehearsal time, and as a result little innovation and exploration.[1] She re-fashioned the theatre as she re-fashioned the characters she took on, seeking to bring her own inner life into her characters by radically re-exploring the text. She used subtlety to her advantage while seducing her audience in a world of small, intimate, and brilliant gestures.[2] In William Weaver’s biography of Duse, he recalls “how deeply I was impressed by a single gesture: in one scene: Rosalia–Duse’s character—had to leave the house; she snatched a shawl and flung it over her head with the natural movement of a peasant woman who had been putting on shawls for a lifetime, as her mother and grandmother had worn them in lifetimes before hers. The movement was…unsophisticated elegance.”[3] To Duse, acting did not exist on the surface but came from the authentic search for human truth on the stage.[4]

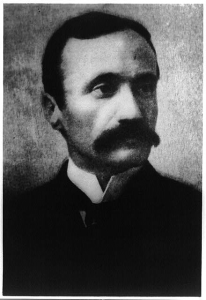

While Duse explored many avenues of performance, it was clear that modern roles suited her far better than Shakespeare. This reality explains why enthusiastic supporters of her work felt that she did not encapsulate Shakespeare’s voice when she produced the expensive adaptation of Antony and Cleopatra, penned by her lover Arrigo Boito (shown at right).[5] Duse’s style, technique, and artistry was simply meant for the more modern plays that were created in her time. However, her Italian repertoire failed her in that respect too, and she sought other works to revolutionize as her career continued. Duse’s primary reason for exploring the works of the modern stage was to enhance her vast talents.[6] Good was never good enough, deep could always be taken deeper, and there was no limit to what she would do to enrapture her adoring audiences. To so great an actress, “it was that no matter how meagre the dramatic material she was given (and much of her repertory was thin) she succeeded in finding the means of tapping values that none had discovered there before.”[7]

While Duse explored many avenues of performance, it was clear that modern roles suited her far better than Shakespeare. This reality explains why enthusiastic supporters of her work felt that she did not encapsulate Shakespeare’s voice when she produced the expensive adaptation of Antony and Cleopatra, penned by her lover Arrigo Boito (shown at right).[5] Duse’s style, technique, and artistry was simply meant for the more modern plays that were created in her time. However, her Italian repertoire failed her in that respect too, and she sought other works to revolutionize as her career continued. Duse’s primary reason for exploring the works of the modern stage was to enhance her vast talents.[6] Good was never good enough, deep could always be taken deeper, and there was no limit to what she would do to enrapture her adoring audiences. To so great an actress, “it was that no matter how meagre the dramatic material she was given (and much of her repertory was thin) she succeeded in finding the means of tapping values that none had discovered there before.”[7]

Many tales of theatre lore describe how Duse had an unnatural ability to transform her appearance without the use of makeup and physical aids.[8] Her colleagues, including fellow actor Guido Noccioli, recall how she did in fact use makeup, but with a level of skill that enhanced her inner energy and finesse, so that it went unnoticed by many.[9] Duse was ultimately a craftswoman, and her commitment to her craft offered the world a style of acting that was not replicated in her part of the world for decades. Despite her greatness, Duse was never a slave to her ego. She shunned her ambition and sought God through and by her work.[10]

While an artist of the stage, Duse made one brief move to the cinema, starring in Cenere in 1917. While the early film was not a success, Duse realized that her style of acting was well suited to the medium, and she was quoted in saying that if she were twenty years younger, she would have made her name in motion pictures.[11] Her artistic style serves as a precursor to the deeply riveting, human acting that audiences come to demand today. In Duse’s time, she was a celebrated rarity of the theatre.

While an artist of the stage, Duse made one brief move to the cinema, starring in Cenere in 1917. While the early film was not a success, Duse realized that her style of acting was well suited to the medium, and she was quoted in saying that if she were twenty years younger, she would have made her name in motion pictures.[11] Her artistic style serves as a precursor to the deeply riveting, human acting that audiences come to demand today. In Duse’s time, she was a celebrated rarity of the theatre.

- Bassnett, Susan. “Duse, Eleonora Giulia Amalia (1858–1924).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Re, Lucia. “Eleonora Duse and Women: Performing Desire, Power, and Knowledge.” Italian Studies, vol. 70, no. 3, 2015, 351.

- Weaver, William. Duse: A Biography. Harbourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, 1984. 7.

- Re, 355.

- Sica, Anna De Domenico. “Eleonora Duse’s Library: The Disclosure of Aesthetic Value in Real Acting.” Nineteenth Century Theatre and Film, vol. 37, no. 2, 2010, 70.

- Fisher, James. “Duse, Eleonora.” American National Biography Online, Oxford Unniversity Press, 2000.

- Longman, Stanley Vincent. “Eleonora Duse’s Second Career.” Theatre Survey, vol. 21, no. 2, 1980, 169.

- Pontiero, Giovanni, editor and translator. Duse on Tour. The University of Massachusetts Press, 1982. 8.

- Bassnett.

- Le Gallienne, Eva. The Mystic in the Theatre: Eleonora Duse. Ambassador Books, Ltd., 1966. 15.

- Fisher.

Photographs: Left: Arrigo Boito. [No Date Recorded on Caption Card] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <https://www.loc.gov/item/2002714212/>. Right: Cenere Movie Poster. Retrieved from IMDB. <http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0006494/?ref_=ttmi_tt>.