Technology: once removing borders, now reinforces them.

The idea of physical borders to distinguish geographic areas is something, that while once was based on protecting those it contained, is becoming increasingly counterproductive. Today’s world is moving towards increased physical and virtual connectivity – in ways that are defining postmodernity. The idea of a post-modern “time-space compression” comes from the geographer David Harvey in his book The Condition of Postmodernity (1989). Discussing the phrase he states, “I use the word ‘compression’ because a strong case can be made that the history of capitalism has been characterized by speed-up in the pace of life, while so overcoming spatial barriers that the world sometimes seems to collapse inwards upon us.” (Harvey, 240) Taking this one step further, Doreen Massey highlights a “power geometry” embedded in this recent time-space compression. Massey writes in Space, Place, and Gender, “If time-space compression can be imagined in that more socially formed, socially evaluative and differentiated way, then there may be here the possibility of developing a politics of mobility and access. For it does seem that mobility, and control over mobility, both reflects and reinforces power…the mobility and control of some groups can actively weaken other people.” Massey underscores how in a shrinking world having mobility and being able to navigate that world becomes more and more valuable.

Borders, which were originally intended to protect groups of individuals, no longer accomplish the same goals. They act as an obstacle to a mobility that is defining the newest age of humanity. Their initial goals of protection are easily undermined through various mechanisms, such that they represent increasingly forced “ideals” by governments (think, the Great Wall of China or Germany during the cold war.) What were once literal barriers to foreign or hostile elements have become symbolic of division and isolationism. Borders today act to heighten isolation and prevent cultural and social exchange.

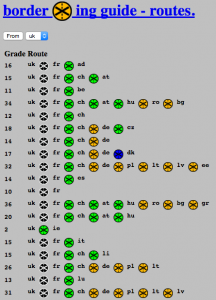

BorderXing Guide (2003, Heath Bunting), for example, was a project in which Bunting worked to cross borders between various European Union countries without having to interact with authorities or going through legal customs. Often involving rafting across rivers, cutting fences, or surreptitiously crossing private property Bunting’s project can now be used by NGOs and aid organizations to support refugees. BorderXing, however, is not published in its complete form online. Publishing such content online would enable a level of visibility for the EU’s governing bodies to be able to monitor or repair any of the paths that were discovered or forged in the process of the piece. In order to subvert the set borders and surveillance imposed by many states, this piece had to move away from technology to bring people together – something that people claim technology does. The borders that are imposed between different countries are no longer protecting the people, so the people have to undermine them.

courtesy of Heath Bunting’s website

Another example of a situation where traditional border subversion can be found in intentional communities that are focused on community and cohesion. Intentional communities resemble the practical application of the ideas behind many works of contemporary art in all its many forms. One example has the mission of collective ownership and support can be found in Denmark’s capital Copenhagen. The 84 acre, Freetown Christiania was “declared” in 1971 and has since existed as a collective of around 850 that actively operate against the status quo by focusing on collective ownership of housing and goods. Notorious for its “Green Light District” where marijuana is publicly sold on Pusher Street, Christiania is much more than a group of people looking to sell and take drugs – it strives to be an alternate to the normal government of Copenhagen and acts as an evolving experiment that strives to become a communal Utopia. Home to museums, an art gallery, a concert venue, a grocery store, a building supplies store and more, it is a fully fledged community. After a decade of fighting, Christiania and the city of Copenhagen have come to a semi-permanent solution in which a recently formed (by the residents) foundation “owns” the 84 acres and residents all own “social shares” – a compromise to fit the government’s privatization needs and the resident’s community ownership ideals. It now lies somewhere between a commune and an artist collective. Christiania rebukes private land ownership while simultaneously undermining the Danish government’s claims to lawmaking over all of the physical land that they deem as Copenhagen. It stands to say that there is not one way to divide land and that there are alternative ways of living, thinking, and organizing with those who are around you.

Sign upon exiting Christiania

Internet technology, in its current state of development, goes unquestioned by most of its users. There has been little infrastructure or legislation developed surrounding personal privacy online (or even rules of cyber warfare) that protect the people – and yet increasingly more and more elements of our lives incorporate the internet, often unnecessarily. Additionally, new technologies themselves often undermine or increase risks for those who attempt to subvert borders and man made boundaries through various practical applications. For example, the public documentation or distribution of the BorderXing information or photographs of those selling marijuana or abiding by Christiania (not Copenhagen) laws. Technology often serves to reinforce borders, in contrast to how it is often and was originally seen to remove them as it worked to reinforce the time-space compression of post modernity. As the world becomes increasingly small and mobility becomes more fundamental to human life, technology and physical borders need to be re-envisioned, revitalized, and move towards flexibility instead of division.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.