Consumerism, identity, and new media: the Taylor Swift – Kanye West divide

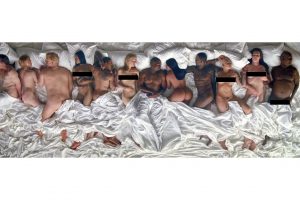

While the tale begins in 2009, this chapter begins on February 11, 2016: Kanye West released his new song “Famous” off his album The Life of Pablo (2016). The song features the line: “I feel like me and Taylor might still have sex / Why? I made that bitch famous.” The real Taylor Swift quickly responded saying that the lyrics were misogynistic and offensive. Shortly after, however, Kanye and his wife Kim Kardashian West spoke out claiming that Kanye had discussed the lyric with Taylor and that she had approved it – a statement Swift quickly denied. The video for “Famous” was released on June 25th featuring wax figures of prominent famous people all in bed naked (including Bill Cosby, George Bush Jr., Amber Rose, alongside Kanye, Kim and Taylor – and more.) Adding more fuel to the fire, on July 18th Kim posted a video on the social media platform Snapchat of the supposed phone call between Kanye and Taylor in which Taylor hears and approves the lyric “I feel like me and Taylor might still have sex.”

Still from Kayne’s video for Famous (2016)

The Taylor Swift-Kanye West feud captures the way that social media and other new media are allowing people to construct, curate, and manipulate, while sometimes failing to protect, their identities. While at first glance this is just a trivial feud between a few pop stars, a deeper look reveals the larger cultural phenomenon revolving around the careful exposure and (perceived) concealment involved in forming an identity in a world increasingly dependent on the internet for social interaction and global connection. While celebrities may see a large monetary consequence when their “image” is disrupted, younger generations, too, are prey to increasing anxieties about online and social image in a way that redefines who or what a “self” is. Apps and websites like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, Tinder, even Venmo all become forms of new media that blur the line between physical self and a curated collection of memories constituting one’s self.

The question of identity isn’t new. In fact, two philosophers wrote profusely (in the 17th and 18th centuries respectively) on the subject in ways that still shape discourse surrounding it today – John Locke and Joseph Butler. While disagreeing about the fundamental meaning and composition of identity, both emphasized the aspects of comparison and memory as being strongly related to it. Locke believes that by using comparisons of time and place you can get to the core of “identity” and “diversity.” In An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690), he begins the chapter “Of Identity and Diversity” by stating, “when we see anything to be in any place in any instant of time, we are sure… that it is that very thing, and not another which at that same time exists in another place, how like and undistinguishable soever it may be in all other respects: and in this consists identity…” Here, identity is singularity: in any given moment any existing thing is inherently itself. Locke continues, “that, therefore, that had one beginning, is the same thing; and that which had a different beginning in time and place from that, is not the same, but diverse” implying that that which makes us “diverse” (or distinguishes us from things around us) is based in the experiences that each individual has lived since their beginning. For Locke person one (at time = 1) is only the same as person two (at time = 2) if person two has the memories of person one. To him identity is forged in the comparisons that are drawn between individuals in a given moment, as well as in the conglomeration of the memories that are comprised of these moments.

In “Of Personal Identity” from The Analogy of Religion (1736), Joseph Butler first uses logic similar to Locke, but ultimately (and notoriously) disagrees with him. Butler, using the examples of two alike triangles and the difference between “two times two” and four in order to discuss how the mind conceptualizes “similitude” and “equality,” claims that our existence at different moments evokes the same type of comparisons: “[the] comparison not only gives us the idea of personal identity, but also shows us the identity of ourselves in those two moments; the present, suppose, and that immediately past.” Butler evokes the same sense of comparison as crucial to identity as Locke, and also like Locke, he engages with the idea of identity remaining recognizable over time. Butler, however, argues that memories cannot define identity, but are only a principle mainstay in the self awareness of identity: “consciousness of what is past does thus ascertain our personal identity to ourselves… consciousness of personal identity presupposes, and therefore cannot constitute, personal identity” – who is to say that that which you forget did not affect your identity?

While Butler and Locke disagree on which came first, the memory or identity, they both heavily utilize language and ideas about time, memory, and comparison in their discussions about identity and identity formation. So, how has new media changed this? One way is by eliminating the vagaries of memory and exponentially increasing the opportunities for comparison. If identity is some combination of comparison, memory, and time, then, social media is the ultimate tool for identity construction. It is a technology custom-built to date, organize, remember, and share your memories in comparison to peers for you.

https://orangecrocodileknight.files.wordpress.com/2013/09/social-media.png

There is no denying that beyond celebrities, individuals on social media are increasingly aware of the identity that they are projecting through social media. While this is explicit on dating apps (this site will even supposedly review your Tinder profile for a small fee of $139 to double your matches) it is clear across social media sites. External representation becomes a focus for instant gratification, a design element that is deeply embedded in the platforms in the form of likes, shares, and retweets, they are designed to tell a user what the correct memory to share is and what should be hidden or forgotten. But the world of social media and identity construction goes deeper than what is clearly seen or represented to peers and becomes an amalgam of commodification both in terms of what identities people are trying to sell themselves and what we often forget is being sold about the users in the form of data mining and profiling. Jill Walker-Rettberg, a digital studies scholar and professor from Bergen, Norway, wrote in her book Seeing Ourselves Through Technology (2014), “self-representation with digital technologies is also self-documentation. We think not only about how to present ourselves to others, but also log or record moments of our lives for ourselves to remember them in the future,” implying that the way that we use social media acts as a “log” or “record” for both others as well as ourselves – digital representation acts as memory, but more than that it acts as memory’s darker counterpart, documentation. Walker-Rettberg goes even further, beyond what we actively seek to put online, to discuss the information that we happen to leave behind, “in addition to our intended self-representations, our digital traces are being gathered by entities far beyond our control: government agencies, commercial companies, data brokers and possibly criminals. We have little or no access to these representations of us, although the data that shapes them comes from us.“ What we put out there as our “identity” will inevitably be read differently and manipulated by different parties.

What Locke and Butler could never have predicted was a world in which a person’s memories and sense of identity isn’t under their own control. People can choose, for example, to show their families (like Kim and Kanye) or rarely show their family and instead focus on their friends (like Taylor Swift.) Curating (some might say, “rigging” ) these identities are crucial to these celebrity and personal brands. It adds to their commodification through advertisement and product placement. In posting images of her with lots of female friends or various committed boyfriends, Swift, for example, often appeals to younger women who are looking for a specific type of role model that is anodyne, that says it’s ok to be nervous, scared, innocent, and also carefree and explorative. Kardashian-West, notably posting provocative selfies and is often robustly showing support for her family, is for a more experienced, less innocent audience that is more raw and sometimes complex. Furthermore, Kim Kardashian-West’s identity often relies on the defense of her family, whereas Kanye has a much less public and voiced social media identity, therefore by having Kim take on Taylor, Kim and Kanye are maintaining the expectations based in their constructed identities – and so the debate becomes about Kim and Taylor. Notably, they both have chosen public identities that are directly linked with how they are commodified in culture and with how much they believe that they should or should not share, a commodification that is guided by the celebrity and their PR team, but is aided and abetted by the audience. In either case, they are playing a game of compare and contrast with social media in order to further their identities and carve out distinct places in the entertainment industry. However, in publicly releasing a private video, Kardashian-West disrupted Swift’s constructed identity – an event that could do immense damage to Swift’s current brand or that could be forgotten as soon as the newest memory (in the form of an Instagram photoshoot, of course) supplants it. While identity used to be a generally private phenomenon, today it is projected through a loudspeaker for the individual to profit.

Speaking about the leaked Snapchat video of Taylor approving Kanye’s song lyrics, Charlotte Cotton, a curator at the International Center of Photography in New York, said she sees, “a direct relation between Ms. Swift’s romping [fourth of July] photos [on Instagram] and Ms. Kardashian West’s leaked video, which she explained as a kind of celebrity brand smackdown.” The images of Kim and Taylor are often positioned as in direct opposition to each other, that there must be a “winner,” while this may or may not be true, in posting the video on Snapchat, Kim is directly violating Taylor’s image by revealing a private conversation – both by social standards as well as legal ones. In doing so, Kim also broke the boundary between what an audience can believe about an online identity and called into question all of the trust that is placed onto that precarious term. As with most scandals, however, this one will blow over and ultimately, Kim’s and Taylor’s identities will be re-formed. They have mastered the art of revealing just enough to fit into their desired public identity and have both found a space that provides endless comparison and, consequently, a continually maintained identity in the public eye, one that funds their lifestyles.

[…] We now have unprecedented access to the lives of those in Hollywood thanks to social media. Image, presentation and perception has never been such a valuable commodity, all held together by the linch pin that is social media. […]