Can re-commodifying a body act as reclaiming?

The female body has been serially fragmented and commodified for centuries. The most frequently accepted modern manifestation of this in the western world that continues today is found in all forms of art. It occurs not only in stories and plot, for example, Adrienne Ward highlights while reviewing Maggie Günsberg’s book Playing with Gender: The Comedies of Goldoni (2001), the basic foundations for females as plot devices. Females are seen as bargaining chips with value only derived from the physical body, Ward writes: “female bodies as the principal object of negotiation in strictly-male power relations, crucial to patrilineality… The high value accorded a chaste woman’s body also renders it susceptible to corruption, requiring male policing.” The constant reducing and policing, not only of the body itself, but further the ideology around it, create a positive feedback loop, leading power dynamics to become increasingly imbalanced. Furthermore, those that own and possess the body are able to commodify and profit from it.

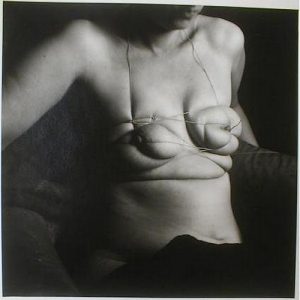

A clear example (although almost any modern art employs this technique) arises in surrealist art, particularly through twentieth century artist Hans Bellmer. Fragmenting and reassembling ‘dolls.’ Bellmer creates many grotesque recreations of the female body, often recreations that remove heads or torsos by splicing two sets of legs together at either the pelvis or lower abdomen. In photographs of his wife, he pulls string tight across her breasts and legs evoking ideas of bondage, cuts, and eroticism, rarely does he reveal her face, head, or unaltered body in any image.

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/494551602807387197/

If these examples sound graphic, extreme, or not present in mainstream art, then one simply has to think of the many depictions of Venus and the Madonna in more classical art. These figures are typically depicted to tow the line between reproductive and naive, reinforcing ideas that a female’s value (or selling point) is in her reproductive ability. As Lesley A. Sharp puts it, in The Commodification of the Body and Its Parts (2000), “women consistently emerge as specialized targets of commodification, where the female body is often valued for its reproductive potential.” From visual art, film wasted no time in becoming the newest manifestation of the age old ideology and practice of commodifying the female body. Just think of any major hollywood film franchise, it was most likely directed by a male and features a damsel in distress depicted in a voyeuristic way (think Bond girls). Is it possible to reclaim a form that has been and is repeatedly, serially, and inappropriately deconstructed, commodified, and sold in a capitalist patriarchal society?

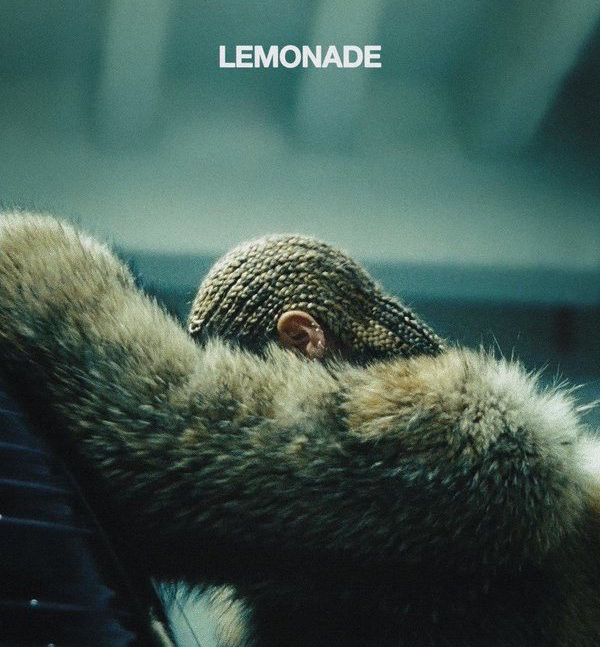

While this may seem like a daunting task, it seems that people are rising to the challenge. A notable trend is the use of contemporary comedians, actresses, writers, and singers to discuss and work with their own bodies in their products. Recently on April 23rd, for example, Beyoncé released her video album Lemonade (2016) without prior notice both on HBO and the online streaming service Tidal. Lemonade features a spoken word poem (written by Warsan Shire) interspersed between a series of music videos. It tells the story of a woman as she finds out about, processes, and recovers from her husband’s infidelity (rumored to be based off of Beyoncé and Jay-Z’s relationship.) It was a collaboration between Beyoncé and 7 other directors and makes use of a myriad of film techniques (not all of which go necessarily well together) including black and white and color, widescreen and fullscreen, crystal clear digital video and super 8 and so on.

Instantly inciting debates about her artistic creativity, feminism, and, ultimately, her use of her body, Beyoncé is running head first at the question as to how to reclaim not only female bodies, but black female bodies. The film was met with controversy from those who thought that she was either perpetuating and feeding into the commodification of female bodies in order to profit and also from those who thought that the story undermined feminist work and theory. One New Yorker theater critic, Hilton Als, wrote an article on Lemonade, titled “Beywatch” (2016) that very clearly revealed his inability to understand the breadth of a male dominated society. Describing his experience of a Beyoncé concert Als wrote,

“Beyoncé gave the black and Hispanic women I saw outside and then inside the [venue] permission to flaunt the things that make them unpopular in a world that thrives on Beyoncé-style klieg-light success: their coloredness and their weight. As pleasurable as that was to witness, the means by which Queen Bey, as many of her fans call her, has achieved her success worried me. None of it has been separable from men.”

In one stroke objectifying the women at the concert (“as pleasurable as that was to witness”) and simultaneously misunderstanding the complexity of gender dynamics and the patriarchy by criticizing her dance, dress, and storytelling as not having ever “been separable from men,” this article highlights how when men use female bodies it is status-quo or acceptable, however, when a female chooses to embrace her body it somehow undermines her entire success because she choses to use commodification as a tool as well.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/video/entertainment/decoding-beyonces-visual-album-lemonade/2016/04/26/fef40222-0b3b-11e6-bc53-db634ca94a2a_video.html

https://www.washingtonpost.com/video/entertainment/decoding-beyonces-visual-album-lemonade/2016/04/26/fef40222-0b3b-11e6-bc53-db634ca94a2a_video.html

Another notable critic of Lemonade, but also of Beyoncé’s version of feminism more generally, is bell hooks. Most notably calling Beyoncé a “terrorist” at the New School’s panel “Are You Still A Slave? Liberating the Black Female Body” in New York in 2014, hooks ultimately believes that we need a vision of liberation that “are away from not an inversion – of what society has told us” furthermore, she believes that discussions about Beyoncé that revolve only around her gender and race while ignoring her class and wealth. Publishing Moving Beyond Pain, just days after Lemonade’s release, Dr. hooks’ tears into Beyoncé again. Her primary issues abound from the fact that Beyoncé is using her body to make money and that Beyoncé is reinforcing ideas about female irrationality in the name of healing from betrayal. Salon writer Lasha gives bell hooks a run for her money saying, “we cannot move beyond the myriad of norms that comprise society’s restrictive definition of what womanhood is and what its acceptable utterances and displays look like by simply replacing them with new, yet just as restrictive, norms.“

Continuing this thought Lasha writes, “Undoubtedly a woman’s value should not be reduced to the usefulness of her body in exciting and enticing the carnal senses. Neither, then, should a woman’s value be reduced by her ability to use her body to excite and entice carnal senses.” This is exactly the point that Hilton Als and bell hook miss – we should not be reducing the value of woman in any way that relates primarily to their body. Beyoncé has attained almost unimaginable amounts of success and increasingly uses that success to express herself in more artistic as well as political ways – all while remaining relevant to mainstream culture and in fact redefining and pushing mainstream culture further in its self awareness.

So, is it time for the female body to be reclaimed from centuries of oppression and dissection? Whether people are ready or not, pop culture is trying to embrace that, but does utilizing the same tools to “embrace” it that were used to oppress it really act as reclaiming?

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.