Female Sexuality in Horror

Entering the second week of the 2016 Edinburgh Film Festival I expected to be burned out from the amount of film halfway through the week, based on past anecdotes. What kept me going–what ironically kept me from getting tired of watching six movies a day–were the midnight screenings at the festival. The midnight shows were more bloody, visceral, thought-provoking, and quotable than their counterpart films during the day. The screening of the 1973 Japanese animation Belladonna of Sadness and the horror anthology Holidays (2016) are just two of these such visceral films that transcend the horror genre.

While Belladonna was not straight horror like Holidays, certain scenes did provoke the same ‘abject’ responses as any other horror films. From Julia Kristeva’s Power of Horror, abjection is the “threatened breakdown of meaning caused by the the loss of distinction between subject and object or between self and other.” Abjection is something experienced before entering the mirror stage of psychosexual development, as in the establishment of boundaries between self and other and human and animal. In horror films, this is usually induced through hybrid monsters like werewolves, or the corpse which reminds the viewer of their own materiality, their own ‘objectness’ while being a gazing subject.

Whereas horror usually moralizes female sexuality (i.e. the ‘sluttiest’ character typically dies first), these two films transcend regular horror portrayals of sexuality by shifting the genre into what could be called the ‘abject weird.’

Two of the shorts in Holidays involve pregnancy, one of the most potent symbols of female sexuality–but not on the women’s own terms. Rather than examples of misogynistic dominance of man over woman, other forces are in play. In St. Patrick’s Day, the pregnancy is induced by a little girl; in Mother’s Day, the pregnancy is orchestrated by a coven of female satanists. In Mother’s Day, the man, presumably Satan, is barely a part of the fertility ritual, only there for the climax. To bring about nonconsensual pregnancies without moralized sex, Holidays trades the agency of the protagonist for abject powers for the female sex. The witches in St. Patrick’s Day and Mother’s Day appropriate the sexuality of other women and force it into the abject. The woman in St. Patrick’s Day ends up coming to terms with her ‘child’, and gives birth to a snake demon, thereby reversing the ‘miracle’ that St. Patrick wrought on Ireland. The captive in Mother’s Day attempts to flee the desert coven but ends up giving birth anyway. At the moment of birth, the viewer is shocked when a bloody, muscled hand grabs onto the ankle of its mother, preparing to pull itself out of the womb. She’s presumably given birth to the Anti-Christ.

These two shorts in the Holiday horror anthology take the normative female role as mother and makes it abject. In St. Patrick’s Day, the barrier between human and animal falls apart, especially when the druids with animal heads appear to herald the return of snakes to Ireland. The abject is sudden and startling in Mother’s Day when a bloody adult hand emerges from the mother’s womb.

In New Year’s Eve, another short from Holidays, a male serial killer goes on the prowl for another victim. Through an online dating site, he meets a woman with whom he has dinner. Inexplicably invited back to her place, he is in the bathroom preparing to chloroform her. He opens the bathroom cabinet to find the testicles of his prey’s own victims. In the bath behind the shower curtain are two bloodied corpses. The woman ends up breaking down the bathroom door with a fire axe, and a struggle ensues during which his foot is chopped off and ending with her impaling her axe deep in his skull. New Year’s Eve reverses the sexual roles of male predator and female prey using shocking abject images, culminating in a satisfying murder. At the midnight screening, the audience cheered when the female serial killer finished off her male counterpart, turning on its head the tradition of male slashers offing unsuspecting women. The switching of the sexual roles created a cathartic abject reaction in the audience, in which we identified thoroughly with the killer, and so participated in the act of death, rather than being passively witness to it.

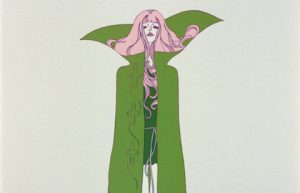

Belladonna of Sadness, a vintage Japanese film that reimagines the story of Joan of Arc in a viscerally erotic retelling, follows many of the same lines of Holidays. The film opens with her rape at the hands of the King, the court depicted abstractly as her body is torn in half by a massive red thrusting. Jeanne is smart and hardworking and first parlays these skills into first supporting her husband, Jean, as he works as a tax collector. When Jean is maimed for failing to collect, it is Jeanne who becomes the main moneylender and powerhouse in the town while the King is away at war. When the King returns, the jealousy of his wife and the obvious admiration that the commoners have for the low-born Jeanne lead the King and Queen to accuse Jeanne of witchcraft.

Betrayed by her husband and her home, Jeanne retreats into the wilderness. There, the phallic spirit that has been encouraging her to take revenge on the King reappears. Revealing himself as the Devil, he offers to make her a witch in exchange for consummation. Trading eldricht powers in exchange for a tumble with the Devil might seem like a moral quandary. However, as a poor woman in the middle ages accused and hunted for witchcraft, she has almost no options besides parlaying her sexuality for safety. During the consummation, rather than showing Jeanne’s acceptance or disgust of her decision, moralizing the sex, she climaxes into violently colorful and funky imagery. Mushi Production took every abject image from 1960s and early 70s psychedelics and smashed them into Jeanne’s endorphined mind. Jeanne goes on to become a witch and healer for the town, living in the woods, healing the sick and leading orgies for the town. These orgies are the most sexually abject of anything in the film. The townspeople’s sexual organs become animals and trees and other strange phallic or vulva shaped objects. All meaning to the partiers’ sexual identity collapses as the distinction between self and other collapses, as the townspeople smash and fuse with each other in bliss, as well as between human and animal, as the people become hypersexual bestial hybrids.

Both Belladonna of Sadness and Holidays use the abject to transcend the normal sexual roles women play in the horror genre. Even without feminist thought, the abject is more interesting than traditional roles the viewers have seen played out over and over on the big screen. The subsumation of the traditional film into the ‘abject weird’ was my savior during the EIFF, a strange, ghastly light in between hours of studio and arthouse films.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.