The basement of the Baker Library, the academic heart of Dartmouth, houses the nationally recognized Epic of American Civilization by José Clemente Orozco. This fresco is a well-known art piece on campus and is predominately appreciated as such. However, the Orozco murals have a lesser known counterpart known as Walter B. Humphrey’s “Hovey Murals.” The purpose of this essay is to delve into the fruition and authorization of The Epic of American Civilization as well as the “Hovey Murals” at Dartmouth College and how the consequent choice of censorship—or lack thereof—was made. Ultimately, I will conclude with how the accessibility of the Orozco murals resulted in the general awareness and familiarity to students across campus opposed to the “Hovey Murals.” Lastly I will offer my opinion on what should be done, in terms of censorship, to the “Hovey Murals.”

In order to fully grasp the materialization of the “Hovey Murals,” José Clemente Orozco’s murals at Dartmouth College, The Epic of American Civilization must be discussed. The Orozco murals were a result of a larger campaign in the United States. In the 1930s there was a new federal commitment to public art due to the Great Depression. This is what influenced the art professors in the Studio Art department at Dartmouth College to persuade their academic administrations for the funds to bring this Mexican artist to Dartmouth College. Art history professors Artemas S. Packard and Churchill P. Lathrop, approached Orozco with the support of President Ernest Hopkins to be a visiting artist at Dartmouth College. The motivation to bring in Orozco stemmed from the concerns of the art history professors. Both were concerned that students wishing to learn about an artist’s studio activities had no resource for academic support.

Early in 1932, the two recognized that the art department had a small lecture budget, so they decided invite Orozco to give a lecture-demonstration on fresco painting. They believed even a small mural would have educational value to the students. Since this revelation took place before the The Federal Art Project began in 1935, Packard and Lathrop were at the vanguard of the idea of commissioning artists in the United States. This was the action that sparked the genesis of the Orozco Murals.

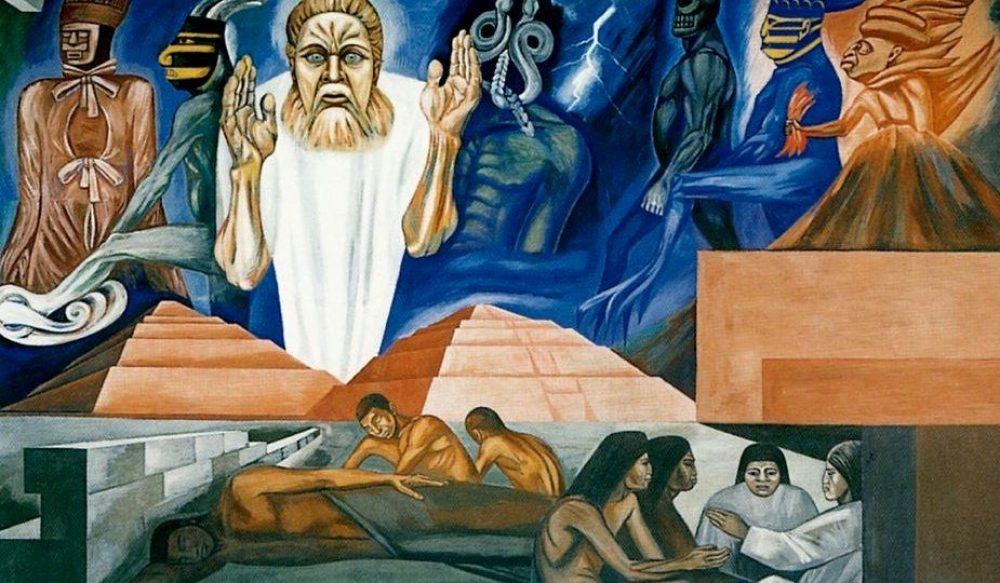

Figure 1: Man Released from the Mechanistic to the Creative Life. Jose Clemente Orozco. Carpenter Hall Corridor

Once Orozco had had some time on campus, he showcased his sample work in a library corridor. The undergraduate body became tremendously impressed with him and his technique. There are accounts of while he was working, students would gather in numbers to watch Orozco paint. It was after his initial project that he presented at Dartmouth that Orozco proposed the murals that would The Epic of American Civilization. According to documented conversation (Oral Interview Between President Hopkins and Mr. Lathem), President Hopkins states that Orozco came to him with a portfolio and a plan for some murals that he’d been carrying around. For years Orozco was looking for the proper wall space and told Hopkins the basement of Baker library was perfect for what he had envisioned. Hopkins then authorized these paintings for Dartmouth College.

In addition to funding from the college, there was outside funding. Chief among this was the funding provided the Rockefeller family. Nelson Rockefeller, Dartmouth Class of 1930, had been a student of Lathrop’s, and a tutorial fund for special educational initiatives set up by Nelson’s mother, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, would ultimately make the commission possible. It is important to note who pays for such projects because in order to receive such funding, the project must be an of how their money is being spent. Once Orozco had preliminary sketches drawn, they were published in The Dartmouth. It was at this moment that this piece of art became controversial.

According to Mary Coffey, “Orozco presents America’s epic as cyclical in nature, the eternal return of destruction and creation, rather than a linear tale of democratic expansion and progress. (Coffey)” I like this description of the murals because it articulates precisely how Orozco illustrates a sense of time by dividing the basement into two parts, the “ancient” and “modern” epochs. Orozco further exploits his idea of cyclical time by drawing analogies between the two periods with coordinating color and certain details. Furthermore, Coffey states, “Ancient America begins with the migration of peoples into the Central Valley of Mexico and the arrival of Quetzalcoatl, an enlightened deity who establishes a Golden Age in which the arts, agriculture, and society flourish. Quetzalcoatl’s departure marks the decline of the ancient world and its destruction by conquistadors enacting Aztec portent. Modern America begins in Christian conquest, presided over by Cortez, Quetzalcoatl’s antiheroic counterpart. (Coffey)” It is after this moment in the mural that the panels shift to modernity’s dark lens. Human industry is developed and “individuality is deadened by a consensus society and the regimentation of standardized education.

The cycle culminates in the blind fury of nationalist war and a Christian apocalypse.” (Coffey) The mural comes full circle when the resurrected Christ destroys what he helped to create like Quetzalcoatl before him. He chops down his cross and “migrates” the spirit toward a new millennium in which modern industrial man might bring about another Golden Age (Coffey). The points about education, in addition to the depictions of Christ, are what brought the main wave of opposition against the Orozco’s murals.

There was much correspondence between alumni and Hopkins in which they expressed their negative feedback on the content of the murals in relation to Dartmouth culture. One such letter was dated June 3, 1932, from alum Matt B. Jones, president of New England Telephone and Telegraph Company, to President Hopkins.

“My feeling about the murals is that when the College makes them a part of a building it stamps with its official approval of the type of art to which the particular mural belongs. I believe my thought is illustrated by the suggestion that there is no reason why the College should not recognize and teach its students the theories and the polices of Socialism, or Communism, or Nudism, or other isms, but it would be a very different thing to carve in stone over the doorways of the College buildings the tenets of those various isms because such action would be equivalent in the mind of the average man to the official adoption and the approval of them by the College (Jones).”

To Jones and many others, the Orozco murals had no place at Dartmouth because they did not, in their minds, depict what the college values were at the time. Additionally, panels of the murals upset some viewers because of the controversial criticisms Orozco paints. Together, these two ideas almost led to the fresco to be painted over. However, it was decided that these paintings would remain accessible to the students and general public.

Orozco painted something that displayed the collision of the indigenous and European civilization on the American continent and the emergence of modern world civilization. The Epic of American Civilization successfully shifts the focus of America’s history from New England to Mexican history from ancient Aztec society, to the invasion of Spanish conquistadors. However, the depictions of the greed of capitalism and deadening conformity of the education system and modern society outraged alumni. One such alum was Walter B. Humphrey, class of 1914. He responded with a mural of his own which he referred to as “a real Dartmouth mural (Calloway).” Originally it was said that Hopkins was interested in a mural depicting Eleazar Wheelock, but in a later interview with Hopkins, he admits that he authorized the “Hovey Murals” in order to alleviate tensions with the alumni outraged by the Orozco mural (Oral Interview Between President Hopkins and Mr. Lathem).

Humphrey designed the first official Indian head symbol for the college in 1932, the same year the Orozco mural was started. This fact is significant because it shows that Humphrey did not understand that the caricaturing of Native people is disrespectful and racist. He used his artist talent to further showcase his ignorance toward the matter in the space of the Hovey Grill. In order to enlist support for his mural Humphrey published a poem outlining his project in a 1937 issue of the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine (Calloway). In it Humphrey states, “So — give me some paint and a wall-space that ain’t All done on the Mexican plan, And I’ll make it sing with verses that ring In the heart of each true Dartmouth man!” This line illustrates that the “Hovey Murals” were his response to what he believed to be Dartmouth culture.

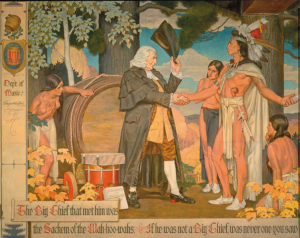

The “Hovey Murals” portrays a drinking song about Wheelock founding Dartmouth by bringing 500 barrels of rum to the New England woods. The song was written by Richard Hovey, class of 1885, hence the name “Hovey Murals.”

The last line of the song sings, “fill the bowl up! Drink to Eleazar, And his primitive Alcazar, Where he mixed drinks for the heathen in the goodness of his soul. (Wurm)” Wurm mentions that there were two Eleazar Wheelocks in Dartmouth “dramatis personae.” There was the tenacious divine Wheelock whose faith carried him to found the college and the comic opera figure celebrated in the drinking song created by Hovey. The way Humphrey misrepresents Wheelock is similar to the way in which he chooses to misrepresent Native Americans—he disregards that which is true and paints them in a way that pleases him and other rich White males. Before the publication of the Eleazar drinking song, Reverend John M. Lord, 1844, with approval of president Tucker persuaded Hovey to change final words of chorus to “in the goodness of his soul” from “for the saving of his soul (Wurm).” Even Humphrey’s source of inspiration was founded on the ludicrous views that later caused these murals to be censored.

Humphrey’s paintings, originally designed to decorate a Dartmouth eatery and to offer an alternative to the “Mexican” fresco, were thought to be fairly innocent and humorous by most of the mainly white and male faculty members and students. The mural depicts the Native Americans that appear, in many cases, to be dumbfound and clueless. The mural illustrates the moment in which these Indians from a make-believe tribe made contact with someone who is “civilized” and would share with them the gift of education.

The art itself is aesthetically pleasing. It may make one feel a sense of happiness from the cheerful colors and cartoon like playfulness.

Throughout the mural narrative, Humphrey makes references to Ivy League rivalries like stealing a drum that clearly is the property of another college as well as references other Dartmouth traditions. Humphrey knew the audience he was painting for, and he painted to please.

In most cases, the natives have European like features. This is mostly true to the depictions of the Native American women. In all of the panels where a woman is present, she is half naked. This was purely for the entertainment value for those who would be in the room. Plate 5, where two Indian women are looking over an upside down book, was one of the most problematic panels in the room.

The two women clearly have European features, suggesting that Native American women were undesirable; they simply were not the type of women whom white men desired. This further suggests that women are merely objects to be sexualized and desired; they are meant to be subjugated to the gazes of men. Additionally, the upside down book insinuates that women are not capable of being academics; it is not their place. As the years passed and more women and Native Americans enrolled at the college, these images were recognized as being racist and sexist.

During the presidency of John Kemeny in the 70s, the college was reminded of its promise of education to Native Americans, the institution discovered to its collective surprise that the Hovey mural was now on the wrong side of history and had become the center of debate; its removal was requested by the Native American Council (McGrath). However, there was monumental resistance from alumni about its removal because they believed that the mural was a central part of Dartmouth tradition. In 1979, after some debate, the mural was paneled over and the Hovey Grill decommissioned. At almost the same moment, the Native American Council decided that it did not wish to embrace censorship, or to flee from a history of bigotry and stereotyping (McGrath). Either option would perpetuate the suppression of problematic historical views. Professor Michael Dorris, chairman of the Native American Studies Program at the time, gave voice to the belief that, if properly interpreted, the murals could serve as a “learning tool” for the broader community (McGrath).

Similarly to Dorris, I believe that the “Hovey Murals” could serve as a powerful learning tool to those who do not already understand why the illustrated images are problematic. Today the “Hovey Murals” are not covered with panels, but are still behind locked doors. Yes, it is true that any Dartmouth student or faculty member may request to see the room through the Hood museum and a curator will open the room and provide a talk highlighting why the mural elicits negative feelings. However, how could one make this request if they do not know the mural exists to begin with? If I were not a Native American student and had not taken a class regarding Mexican murals or murals at Dartmouth, I doubt I would have ever been aware of the murals that exist beneath my feet every time that I eat at ’53 Commons. In my opinion, not opening the murals on the college’s account almost feels as if the college is still trying to forget that these murals were ever part of the overly positive narrative they spew to prospective students about Dartmouth being founded on Native American education. Of course I support the college’s decision on partially censoring the murals allowing them only to be seen along with appropriate commentary, but I also believe the college could do more. If Dartmouth is truly committed to education of Native Americans, they should also be committed to the education of others about Native Americans. In support of this, I request that Dartmouth open its doors to the “Hovey Murals” on its own account maybe once a term (not on a Big Weekend) for the day with a Hood curator. A small announcement could be made that this room will be open to students to visit the room with a curator. This way, the student body will at least be aware that the room exists and could make an appointment to see the room on their own accord.

In retrospect, The Epic of American Civilization became well known to the student body and public because the powers that be decided not to censor them. (This is besides the fact that Orozco was a famous artist beyond Dartmouth in his own right). The ideas portrayed in this mural were deemed not harmful to the college or the public. This is much unlike the “Hovey Murals” which have been forgotten over time due to their partial censorship. Their censorship has led to many of my undergrad peers not being aware of the “Hovey Murals”’s existence. However, it is important to note that the content of those murals are too sensitive to be open freely to students. Therefore, the college had to restrict its access—withdrawing original full authorization—of the murals. All in all, the authorization of the Orozco murals followed by the lack censorship has led to the ultimate acceptance and adoption of the murals into Dartmouth culture where as the “Hovey Murals” symbolize a (hopefully) bygone era within the college’s history.

Bibliography

Calloway, Colin G. The Indian History of an American Institution Native Americans and Dartmouth. Lebanon: University Press of New England, 2010.

(This reference helped me better understand the true history of what it was originally like to be in those founding years of the college and how that ultimately influenced some of the tensions created by the Hovey Murals. Also I found important information pertaining to Humphrey and his connection to creating an image for Dartmouth.)

Coffey, Mary K. Toward an Industrial Golden Age? Orozco’s The Epic of American Civilization. n.d.

(This was an important resource when discussing the Orozco murals. I admire the way in which Coffey flawlessly describes The Epic of American Civilization. Reading her paper also helped me to better understand the Orozco mural and why it offended alumni.)

Jones, Matt B. Telegraph to President Hopkins. Rauner Library. 1932.

(This was a primary document that I found in the Rauner special collections library. It is telegraph to President Hopkins from an alum who became the president of that same telegraph company. I believe this gave him some authority as a successful alum making his voice on the matter slightly louder than the rest.)

McGrath, Robert. The Hovey Murals at Dartmouth College. Lebanon: University Press of New England, 2011.

(This was a reference McGrath’s essay. In it he mostly talks about the history of the mural rather than his opinion and stance on the mural. Since I wanted to develop my own voice on the matter, his essay was helpful in explaining the historical events.)

Oral Interview Between President Hopkins and Mr. Lathem. Rauner Library, 1958.

(This was a primary document that I found in the Rauner special collections library. It was a recorded conversation between retired President Hopkins and a Mr. Lathem that that been transcribed. It allowed me to find the true reason for authorization of the Hovey Murals.)

Wurm, Marie. Eleazar Wheelock. Ed. Held by Rauner Library. Richard Hovey Music Sheet. 1894.

(This was another primary document that I found in Rauner. It was an old piece of sheet music with the notes and lyrics to the drinking song that the Hovey Murals were based on. In the footnotes it mentions some opinions about Wheelock as well as alternative lyrics.)