What is Dengue?

Dengue is a mosquito-borne disease caused by the Flaviviridae flavivirus (DENV), a virus known to be responsible for many diseases including West Nile Virus and Yellow Fever (Dengue Virus Net). According the WHO, DENV can be categorized into four antigenically distinct serotypes (DENV 1, 2, 3 and 4) based on their antibody binding specificity. Upon entering the host, the DENV infects somatic cells and makes modifications that convert normal cells into mass producers of the viral RNA. Each successful invasion yields an exponential increase in DENV agents within the body, causing the victims to become incapacitated in as short as 3 days. Whereas recovery from other viruses generally grants prolonged immunity, DENV does not due to little overlap between the 4 different strains. In other words, recovery from DENV 4 provides little to no cross-immunity against DENV 1, 2, and 3, and can even increase the risks of contraction.

In most of the historically documented cases, dengue fatality remains relatively low albeit its high magnitude of associated discomfort. Within the past couple of decades, however, there has been a significant increase in the number of fatal cases reported. This potentially fatal form of dengue (aka Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever) disproportionately affects those who are geographically sandwiched between the tropics, where high rainfall and mild temperature provide the optimal breeding ground for DENV vectors. Epidemics are also exacerbated by unplanned urbanization, pollution, and lack of sanitary infrastructure, which coincident with many characteristics of countries in the tropical region. In many Latin American countries, including Nicaragua, severe dengue has become a leading cause of hospitalization and death among children (WHO).

The Nicaraguan Context:

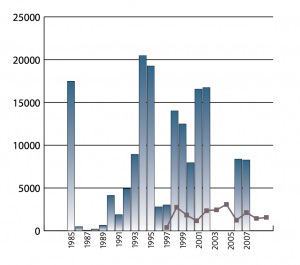

Endemoepidemic behavior of dengue. Peaks are separated by short but variable intervals of low disease counts.

According to Program for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH), dengue displays an endemoepidemic behavior in Nicaragua. Endemic outbreaks are typically followed by short but variable “refractory periods” in which significantly fewer cases of the disease are reported. Historically, the peaks of these outbreaks consistently space two to four yearsapart, but the number of cases reported in consecutive outbreaks has risen dramatically. Between 1985 (initial major outbreak) and 1989, a total of 23,035 cases were recorded in Nicaragua. This number nearly doubled to 61,302 between 1990 and 1997 and then increased by a further 58% to 106,635 cases up to 2007 (PATH). In a span of merely 23 years, Nicaragua witnessed 190,972 dengue incidences, which represents only a portion of the total infected population.

The most recent dengue epidemic, as reported by MINSA, broke out in 2013 between the rainy seasons of July and November. In early summer, the Nicaragua Ministry of Health (MOH) issued the Ministerial Resolution N° 379- 2013 and declared a health alert across the country to prevent and control communicable diseases. A Red Alert was specifically issued to warn of the increase in suspected cases of dengue fever. In a report released by Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF), the confirmed cases of dengue fever increased from 1,817 to 4,939 from Epidemiological week 28 to 43. There were 38,522 additional suspected cases, and a total of 13 fatalities.

Traditionally, the highest incidence rates occur among 5 to 14 year olds. Unsurprisingly, the age cohort also claims the highest morbidity rates. Studies from both PATH and PLOS have validated the above observation, but there has not been substantial research as to why young children are especially prone to dengue hemorrhagic fever. From the gender perspective, women are much more likely to be affected than men, partially due to the system of patriarchy that still thrives in Nicaragua. Women are generally assigned to stay-at-home tasks, confined to small spaces ideal for DENV vector to find prey. Additionally, the expectation and compliance of wearing skirts means a greater expanse of unprotected skin, particularly on the legs, which leaves women more susceptible to mosquito bites.

Transmission and Symptoms:

The Aedes aegypti mosquito is the primary vector for transmission of dengue in Nicaragua. After emerging from the pupae form, adult females must feed on fresh blood in order to acquire the proteins and iron needed for egg production. At this point, the mosquitoes are not vectors yet, as they do not intrinsically carry the dengue virus. After exposure to just a single carrier of DENV, however, they become permanent infected. Infected mosquitoes can transmit the virus to multiple human during its feeding period, providing a positive feedback cycle for the multiplication of DENV in vector and in host.

After entering the victim’s bloodstream, the virus begins its 3-10 day incubation period in which the victim becomes a factory for the mass production of viral RNA. During this period, victims generally experience mild symptoms that could be mistaken for the common cold. However, after the incubation period, the virus “begins” a full on attack on the body. Possible symptoms include:

- Sudden, high fever (up to 106° F)

- Severe headaches

- Pain behind the eyes

- Severe joint and muscle pain

- Fatigue

- Nausea and Vomiting

- Skin rash, which appears two to five days after the onset of fever

- Mild bleeding (such a nose bleed, bleeding gums, or easy bruising)

Dengue has a relatively low fatality rate, and patients usually recover within week after experiencing the peak symptoms. However, the illness can progress into hemorrhagic fever, which causes the victim’s vessels become damaged and leaky. In these cases, symptoms include but are not limited to

- Bleeding under the skin, which might look like bruising

- Problems with your lungs, liver and heart

- Bleeding from your nose and mouth

- Severe abdominal pain

- Persistent vomiting.

In developing countries like Nicaragua, the onset of hemorrhagic fever may already mean that a patient has gone beyond the point of recovery. Often, victims self-diagnose early symptoms of dengue as the common flu and do not heed special attention to their health. To them, subsistence takes precedence over physical comfort, and unless afflicted with a serious condition, many will continue to work arduous hours doing strenuous tasks. When the late stage symptoms set in – heart/liver pain, persistent vomiting, bleeding from nose, etc – their bodies, weakened by daily labor, can easily breakdown without any hope of regeneration.

Treatments/Vaccination:

As it stands currently, there is no specific treatment for dengue. Because dengue is a viral infection, it does not respond to antibiotics. Rest and time are the only components of recovery. Some specific symptoms of dengue, however, can be tended with palliatives. Sustained fevers can be mitigated with medication like paracetamol, an analogue of aspirin. Dehydration due to diarrhea can be resolved via manual maintenance of body salt concentration or through rehydration techniques. Typically mortality rate for sever dengue lies at about 20%, but can be reduce to less than 1% if patients are tended to in a timely fashion and if supplies are available.

There are also no vaccines to protect against dengue, though significant progress has been made in the past years. According to WHO, 3 tetravalent live-attenuated vaccines are under development in phase II and phase III clinical trials. Other vaccine candidates also exist, but are at even earlier stages of clinical development.

Preventive Measures and Government Involvement:

“In 2004, Nicaragua created a national integrated dengue strategy with a behavior-based, multi-sector, comprehensive, and interdisciplinary approach that integrates the following components: social promotion and communication, epidemiological surveillance, laboratory procedure, vector control, patient health care, and environmental sanitation” (PATH).

Nicaragua’s National Dengue Strategy is a multi-pronged approach in combating dengue:

COMBI strategy:

COMBI, also known as “communication for behavioral impact,” aims to modify problematic behavior and conduct within the community that increases one’s susceptibility to dengue. It disseminates dengue booklets that provide elementary school teachers with essential information on the disease to pass on to their students. Students are educated to practice proper sanitation techniques that keep exposure to Aedes aegypti mosquito at a minimum.

Environmental sanitation campaigns:

Sanitation campaigns typically involve procedures that limit breeding grounds for Aedes aegypti. Especially in urban centers, there is an emphasis on proper waste disposal and recycling, which prevent the mosquitos from laying eggs in pools of water that gather in trash such as soda cans and food containers. In 2008 alone, 4 anti-epidemic campaigns were organized to spread awareness on dengue prevention.

Larvicide campaigns and Fumigation:

Annually, the government funds 6-8 national campaigns in which health volunteers travel from house to house to inspect and identify potential breeding grounds for mosquitos (any barrel or container that collects water). These zones are destroyed and sprayed with temephos larvicide in order to prevent future infestations.

Fumigation is another technique of vector elimination. Zones identified by entomological

or epidemiological indicators as high-risk area are completely sealed off and permeated with toxic gases. The preferred insecticide for Aedes aegypti control is cypermetrine (25%) and application is usually executed using a LECO machine with ultra low-volume dispersal. In 2007, a total of 738,398 houses were fumigated with motor-backpack fumigation equipment.

A member of the Health Ministry fumigates a home against the Aedes aegypti mosquito to prevent the spread of dengue fever in Managua, on October 25, 2013.

Outside Assistance: Along with these governmental efforts at dengue control, Nicaragua also receives assistance from a variety of NGOs and non-profit organizations, including Red Cross and Disaster Relief Emergency Fund. Aside from providing monetary support for dengue-related healthcare, Red Cross and DREF are also implementing interventions to prevent the further spread of the disease. Some of the most effective measures taken so far include educating students with the basics of dengue (transmission, preventive measures, and whatnot), and applying insecticides to the heavily infested areas.